House of Seleucus

“We were such a happy family”

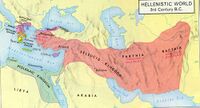

The House of Seleucus were the greatest exporters of Greek culture from the death of Alexander the Great to the arrival of the Romans. For nearly two hundred years, they dominated and controlled much of the Middle East and Persia, much feared by their neighbours. Their only other peers were the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Antigonids in Macedonia. All three dynasties had been founded by generals of Alexander and so saw themselves as something special. And since the Seleucids had ended up with the largest chunk of Alexander's former empire, they saw themselves as the great man's true successors.[1]

Yet today, the Seleucids are barely remembered. The one major exception is that Jews recall how one Seleucid ruler turned the great temple of Jerusalem into a pagan shrine dedicated to Zeus. This would lead to the eventual freedom of Israel and Judea (until the Romans arrived on the scene).

Horse-jockey to ruler[edit]

Seleucus started his career in the cavalry of the all-conquering Alexander. When his boss suddenly died, Seleucus joined in a game of military Monopoly, as each of Alexander's generals thought he was the true successor. Through a Process of Elimination (battlefield deaths in nearly 40 years of constant warfare, or plain old murder), three commanders lived long enough to found dynasties. Seleucus was one of these, and he got the largest geographical slice: an empire stretching from the Aegean Sea to the River Indus in India.

Though Greek in his outlook, Seleucus had carefully to maintain alliances with others. Alexander had obliged all his generals to take a Persian wife to unite the ruling class. When he died, his other generals soon dumped their spouses, but Seleucus kept his and she gave him an heir named Antiochus. Seleucus also formed an alliance with a king in India by ceding territory in exchange for a squadron of war elephants. These were larger than the ones used by the other generals and could out-trumpet any other beast on a battlefield.

In 281 BC, Seleucus became the last great survivor of Alexander's generals by killing in battle Lysimachus, the final drinking-buddy-turned-enemy. Even Ptolemy I had recently died of old age in Alexandria.

Tempting Seleucus to cross into Europe was a chaotic situation in Macedonia and Greece brought about from internal strife and invasions by the hairy Celts. He could re-unite Alexander's empire and in time get around to annexing Egypt to complete the step. Seleucus's dreams ended when he was murdered by one of his palace guests. Ptolemy Ceraunus had been once heir apparent of his father's Egyptian realm but had been exiled. He had taken up residence at Seleucus's court. Disappointed that Seleucus hadn't backed him with an army, the ambitious Ceraunus stole Seleucus's army and invaded Macedonia himself to set up his own realm.[2]

Enemies all around[edit]

Antiochus I succeeded his father. His Greco-Persian background let him pose as a true heir of Alexander and Cyrus the Great — though surely not a peer in military matters. He lost territories (and prestige) to Ptolemy II of Egypt. He married his stepmother Strat-O-Nice, persuading her to leave his crusty old dad for someone much younger. They had five children but when Antiochus's eldest son Seleucus agitated for his father to retire in his favour, Antiochus had Junior executed for treason — then followed him into the afterlife.

Antiochus was succeeded by his only surviving son, Antiochus II. He managed to wrest back earlier losses to Egyptians. A treaty was hammered out between the two empires. One condition for peace was for Antiochus to put aside his wife Laodice (and mother to his current heirs) in favour of Berenice, daughter of Ptolemy. It didn't take a genius to realise that this was going to cause trouble. When Antiochus died, Berenice tried to hold on to power in favour of her own son called Antiochus. Laodice championed her eldest son, Seleucus (as Seleucus II) but they were holed up in Asia Minor. Berenice pleaded for help from her brother Ptolemy III of Egypt. He invaded Syria by sea, cleverly avoiding the Seleucid fortifications in Palestine, then rapidly marched across most of Syria and Mesoptamia, armed mostly with the fiction this war was for his sister Berenice and her baby boy, though both were conveniently dead, killed by allies of Seleucus. Ptolemy scooped up his loot, left a few garrisons around and returned home. Seleucus got Antioch unchallenged but inherited an empire that was now flat broke.

With two rival claims to the Seleucid throne and the intervention of Egypt, several local powerbrokers in the provinces of Parthia and Bactria ('two-humped camel country') broke away under their own rulers. Seleucus's hope to regain them was thwarted when his brother Antiochus Hierax claimed the Seleucid Empire's territories in Asia Minor. Seleucus tried to make his brother change his mind with invasions and battles, but was forced to give in. Seleucus blamed his mother for supporting Hierax and never sent her another birthday card.

Unable to best his brother, take it out on Egypt or regain the lost eastern territories, Seleucus fell into a funk. He took to breeding a new strain of super elephants for future wars. His mood did lighten when Hierax faced his own rebellions in Asia Minor and was forced to flee to Armenia. Seleucus tried to regain territory but was once again defeated. He only cheered up when Hierax attacked him directly in Mesopotamia, only to die in battle. Seleucus held a celebration banquet and then dropped dead just before dessert. His eldest son Alexander came to the throne, changing his name to Seleucus III — certainly not for good luck. Seleucid foreign policy dictated that they had to regain Hierax's old domains — but Seleucid battle prowess did not secure it. Seleucus took it out on his subordinates; and they took it out on him, assassinating him after less than two years in power.

Revival[edit]

The next Seleucid ruler was Antiochus III, who called himself 'Antiochus the Great' and dreamed of reuniting Alexander the Great's empire. How fitting would it be if one Great Greek restored the realm of the Macedonian wonderkid?

To the West of the realm was the Greek-speaking state of Pergamon and around it independent entities like Bythinia and Pontus. Further west lay Macedonia and Greece and beyond them the Roman Republic, which was just coming out of a long war with Carthage. In the East, the rebel provinces of Parthia and Bactria looked well-established. The Ptolemies were still in Egypt and — to Antiochus's shame — the Syrian port city of Seleucia-on-Sea was still occupied by the perverts of Alexandria.[3]

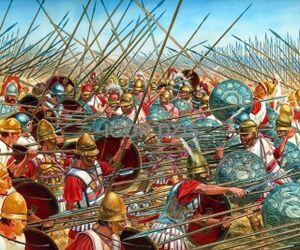

Antiochus's first wars were hasty and unsuccessful. He attacked Egypt directly, with a new batch of war elephants from India. At the battle of Raphia in 217 BC, his elephants overan the inbred African herd of Ptolemy IV[4] but, in a surprise, a scratch troop of native Egyptians showed the Greek-speakers that they could fight in phalanx and win. Antiochus retreated to Syria.

In Asia Minor, Antiochus's cousin Achaeus — hitherto a loyal ally — went solo and broke from the empire. Antiochus eventually tracked him down and had Achaeus executed. The other kingdoms in Asia Minor were obliged to send a big pile of presents to keep Antiochus from attacking them there. These victories and attendant grovelling by the defeated losers encouraged Antiochus to turn East to regain the Seleucid empire's lost provinces there. Parthia and Bactria were defeated in battles but kept their ruling dynasties for now. Finally, Antiochus invaded India. He met success there. The spoils of victory were more elephants for free.

Ahh elephants. Antiochus wanted to have another go at the Ptolemies. This time, he recruited an ally in the ambitious shape of King Philip of Macedon who, like Antiochus, was a descendant of one of Alexander the Great's generals. To help him in his rematch with Egypt, he promised the Macedonians any Ptolemiac holdings in Greece, Asia Minor and the surrounding islands. It was a good time to strike. In 204 BC, Ptolemy IV died/woke up with a dagger in his chest/drank a mislabelled bottle of poison. His six-year-old son Ptolemy V was too young to exercise power, so the court's eunuchs and flunkies tried to take control. Within months, a rebellion saw Upper Egypt and Mezzanine Egypt declare for a new Pharaoh in Luxor-Thebes. Antiochus crossed the frontier and worked his way down as far as Gaza. He annexed the territories and promised to respect existing religious cults/religions including those practised by the Jews and their invisible God. Antiochus was so proud that he called himself Antiochus the Great. All looked good. Then Hannibal, the Elephant Man of Africa, turned up and asked for an audience.

Hannibal joins the payroll[edit]

Hannibal's exploits against the Romans had impressed Antiochus. Now he was a fugitive from Rome, who were dead keen to capture him for his audacity in invading Italy and trouncing the Roman army a number of times. Yet Hannibal lost in the end when the Romans attacked Carthage directly and convinced them to surrender or burn.

The Elephant Man of Africa touted himself as an expert on all things Roman. He accurately suggested that Rome could roll over Macedonia and the Greek city-states, and called on Antiochus to strike first against the 'barbarians on the Tiber' and 'defend the Greek culture' of Socrates, Plato and cheap Ouzo. Tempted and with his Alexander-the-Great illusions, Antiochus invaded Rome — not once but Thrace.

The Romans gave Antiochus's army the slip and turned up instead in Asia Minor. With local allies, the great clash took place in Magnesia. Oddly, Hannibal had been given command of the Seleucid navy rather than the army. Perhaps Antiochus reckoned that Hannibal would outshine him on the battlefield. In fact, it was Antiochus who got the full omelette on his face. His army was beaten, he had to pay a huge fine, surrender all his territories in Asia Minor, give up his fleet, kill most of his elephants, and send his younger son Antiochus Junior as a hostage guarantee. To help pay the fine, Antiochus Senior dabbled in temple-robbing to pay the Romans and got himself killed by angry priests for his pains. It was an ignominous end for the supposed reincarnation of Alexander.

With no ships or an army to command, Hannibal resigned and relocated to the kingdom of Bithynia in northern Asia Minor. He was still Rome's Most Wanted, but out of spite, denied Rome a trophy prisoner and instead killed himself.

Hanukkah[edit]

Antiochus III's successor was his eldest son Seleucus IV. Rome had not forgotten its fine for Illegal Warmaking, so Seleucus had to find the money. He sent a tax bill of his own to the High Priests in the temple in Jerusalem, surely stuffed to the rafters with Jew gold, to protect Judea from the Egyptians and their stuffed-cat religion. When the Romans' tax bills kept coming and started accruing interest, Seleucus sent his son Demetrius to Rome and they returned his brother Antiochus.

Seleucus must have wrung something out of the High Priests, as history records no further complaints from the Romans. However, a disgruntled/ambitious courtier called Heliodorus stabbed Seleucus IV from behind and declared Antiochus (a younger brother of Demetrius) as king. This annoyed the recent returnee Antiochus, who managed to seize power a few months later. Heliodorus was executed. The Junior Junior Antiochus, next in line to the throne at the age of 4, was locked in his playpen and died choking to death on his rattle.

The new ruler was keen to extract more gold for his wobbling empire. He once again pressured the Jews to provide coin. When that wasn't forthcoming, Antiochus Hellenised the temple of Jerusalem, changing its name to the Zeus Lucky Dip Emporium. With that, Antiochus would get all the gold and silver he needed to cross the frontier with Egypt. Pharaoh Ptolemy VI, who was also Antiochus's cousin via his mother being a sister of Antiochus III, saw his army melt away and got himself captured. Ptolemy had been expecting Roman support, but the latter were off fighting a war against Macedonia.

Rome intercedes[edit]

It seemed Antiochus was intent in either taking over Egypt or at least grab money for his own treasury but then news of a rebellion in Jerusalem came through. The Jews had no love for a lucky dip temple and had overthrown all Antiochus's statues including one of Zeus. The rebels mainly came from one family called The Maccabees. They were a grim humourless bunch with an austere view of religion. There enemies were not just the Greek speakers but with anyone who showed a 'hint of Hellenic decadence'. Beards became compulsory and women forbidden to become visible anywhere except their home.

Seeing that a war to surpress Judea was going to take time, Antiochus returned to Egypt. He was met by an elderly Roman ambassador called Gaius Popillius Laenas. With Ptolemy VI hiding in the bushes, Laenas stated that he was the power of Rome. Dare to cross him or face the wrath of that city. The Macedonians and their Greek allies had been crushed. Did Antiochus want the same fate? When the Seleucid ruler started to argue Laenas drew a circle on the ground around Antiochus. If the Greek king stepped out of it without agreeing terms the Romans would take this as an act of war and would attack again. Antiochus reluctantly agreed to leave Egypt and never return. On the way back to Syria he again tried to crush the Maccabees but failed. Antiochus had better luck further East with a war against the Parthians but then died before completing the task in 164 B.C.

Bearded cousins (real and fake)[edit]

The death of Antiochus IV would soon see the Seleucid empire unravel. Antiochus V was another child ruler who didn't last long against another claimant: Demetrius I who, spending two decades as a hostage of the Romans, had picked up several of their habits such as speaking Latin and wearing a toga. Demetrius I was still determined to restore Judea to the Seleucid empire's full control and managed to defeat and kill senior Maccabee leader Judas Macarena (while he was dancing Mambo No. 5).

Demetrius seemed secure on the throne until receiving a letter from an apparent long-lost cousin. This was Alexander Balas, who said he was a son of Antiochus IV. He had a sister called Laodice; Demetrius had never heard of her either. The resulting chaos was a cue for other powers around the crumbling Seleucid empire to grab territory for themselves.

It turns out that Balas was not a Kissing Cousin but a killing cousin; he knocked off Demetrius I and married off his sister to a king of Pontus in Asia Minor. Balas got a bride of his own, Cleopatra Thea, daughter of Balas's chief ally in the alliance, Ptolemy VI of Egypt.

Whilst all this was going on, the Seleucid empire lost Persia to the Parthians. Balas hoped to regain the territories until Ptolemy switched sides and backed Demetrius II, a son of Demetrius I. Cleopatra Thea (who had borne a son to Balas known as Antiochus VI) abandoned her husband and baby and rejoined Ptolemy. She and Demetrius II were married and were soon bouncing royal baby boys on their knees. Balas was killed in battle with his head presented to Ptolemy as a 'precious gift from your ex-brother-in-law'. Ptolemy appreciated the joke but died shortly after.[5] Demetrius insisted that his Egyptian allies leave, lopping off a few heads to emphasise his point. Those who kept their heads complied and returned home.

A general called Diodotus Tryphon now got hold of Thea's eldest son Antiochus VI (by Balas) to use against his mother Cleopatra Thea and Demetrius II. Dispensing with his luckless puppet prince soon after, Diodotus appeared keen to start his own dynastic empire. Most of Syria fell quickly to him. Demetrius II had been unable to respond, as the Parthians had taken most of Mesopotamia and had then improved on that by also capturing Demetrius II. The Seleucid empire appeared to be over; only a few cities still acknowledged the imprisoned Demetrius's rule.

Demetrius's younger brother Antiochus now advanced his own royal claims. Known as Antiochus VII, he married Cleopatra Thea in around 138 BC. She was still legally married to Demetrius, so this was technically bigamy, but she was a product of incest and took the new marriage in her stride. The two at first seemed to be a successful power couple.

Diodotus Tryphon was killed and Mesopotamia largely re-taken from the Parthians. A deal was done also with the Maccabees in Jerusalem. Antiochus apologised for 'earlier misunderstandings' between Greeks and Jews and full automony in exchange for troops if so requested. The Maccabees agreed. Happy Hanukkah to them!

The Parthians stirred up the pot again by releasing Demetrius II. He hadn't had it that bad, living in a comfy palace with a Parthian princess to occupy his time. Demetrius had twice tried to escape but the Parthians always brought him back. Now a new opportunity for freedom arose. The Parthians were worried that Antiochus VII might restore the Seleucids in Persia. Demetrius was set free but had to leave his wife behind. The Parthians were expecting a drawn out struggle but Antiochus managed to get himself killed in an ambush. Cleopatra Thea remarried her returning husband Demetrius II. In his absence, she had produced two more sons by Antiochus VII. One of them, Seleucus, had been captured after the battle, whilst the other, Antiochus (later Antiochus IX), had been sent by Cleopatra to the Greek-speaking city of Cyzicenus on the Aegean coast as a 'precaution' in case his uncle wanted him dead. Dynasties worked best when inconvenient relatives were murdered.

Seleucus banged his tin cup against the bars on his door and demanded his freedom. Finally, the Parthians decided they could use their hostage to do what he was best at: making trouble. They let him out to take the body of his father Antiochus VII to be buried in Syria. However, Seleucus didn't hang around, believing he was safer back in Parthia. He knew his military prowess left something lacking. Actually, everything. Moreover, he was in hot water with the Romans as well, and they had recently annexed Greece and Macedonia, destroyed Carthage, and planted tent stakes in Asia Minor not too far from Syria.

That left Egypt, where a family struggle between Ptolemy VIII (also known as Gutbucket)[6] and his sister-wife Cleopatra II (also Cleopatra Thea's mother) developed into a civil war. Demetrius led an army in support of Cleopatra. Ptolemy responded by producing an adventurer called Alexander Zabinas to cause Demetrius trouble. He also supplied him with an army.

This imposter claimed to be a son of Alexander Balas, whose own relation to the Seleucids was dodgy. Still — imposter or not — Zabinas quickly gained the upper hand against the unpopular Demetrius. The Syrian capital Antioch fell to Zabinas and his Egyptian troops. Demetrius, on the other hand, had got a financial boost when Cleopatra II had fled from Egypt but had thoughtfully brought her country's gold reserves with her. Alas, not a military boost; he lost the war against Zabinas. Thea kept control over the cities that backed her earlier; when Demetrius tried to gain entry to one of them, the gates were closed in his face. Friendless, Demetrius tried his luck elsewhere until he was struck down by one of her assassins. Meantime, Cleopatra II had made peace with her brother Gutbucket Ptolemy, taking what money she had left back to Egypt.

Walls closing in[edit]

These long internal wars shrank the Seleucid empire down to southeastern Asia Minor, Syria, Lebanon, and what is today northern Israel. Persia had been lost in the 140s and Mesopotamia with the death of Antiochus VII. The murderous family squabbles continued. When Demetrius II died, his eldest son Seleucus V briefly became ruler. But he never asked 'Mother, May I?' and Cleopatra Thea had him shot to death by arrows. She then supported Seleucus's brother Grypus,[7] who became Antiochus VIII. Cleopatra made sure she was also co-ruler; though born in Egypt, she felt as Syrian as anyone else in the family.

The imposter Alexander Zabinus was still in control of most of the Seleucid empire, until the next dynastic shift. Cleopatra II had returned to Egypt, where there had been a family reconciliation. In the spirit of amity, Ptolemy VIII deserted Zabinus and supported Antiochus VIII. This was another alliance-by-marriage, as Ptolemy VIII's daughter Tryphaena married Antiochus VIII. Zabinas lost his Egypt-financed army and, shortly after, his life in battle. Another family war was over.

With one dangerous enemy out of the way, it was time for Cleopatra Thea to enjoy family life. She had married three kings and given birth to four others. Unfortunately, she was enamored of intrigue and treachery, especially given the presence of daughter-in-law-and-cousin Tryphanea, whom Antiochus VIII might favour over dear old Mum. Mum realised that the solution was to knock off her son, and maybe invite the surviving half-brother to become ruler. However, Antiochus either got tipped off about the poison in his drink, or knew his mother too well. In any event, the goblets were switched and Cleopatra Thea got the fatal draught.

For a few more years, Antiochus VIII and Tryphanea ruled in relative peace. Tryphaena was adept at filling a family nursery. At least six sons came from this union — all of whom would get their turn on the throne. In 116 BC, the exiled Antiochus returned to Syria to throw his diadem into the ring for the kingship. The ever-helpful Ptolemies supplied him with a queen — this time, Cleopatra IV. The latter had been enthroned briefly as queen of Egypt but lost that title in a struggle for power and fled to Cyprus with her supporters. Cleopatra was as productive as her sister Tryphanea, producing two future kings of Egypt, a queen of Egypt and a king of Syria. Cleopatra didn't live to see any of this, as she was captured by Tryphanea, who had her sibling done to a very public death in 112 BC. Antiochus VIII objected but wasn't strong enough to stop this murder. The following year, Antiochus IX got a chance for revenge. Tryphanea was imprisoned after losing a battle, and Antiochus IX effectively sacrificed her on his dead wife's tomb.

Last knockings[edit]

With so many Seleucid wannabe kings around and ready to kill each other, eventually even Syria wasn't safe for the Syrians. The entire family appealed for allies, with promises that could never be kept. In 75 BC, Tigranes King of Armenia invaded Syria and seems to have taken nearly everything. The last major resistance came from another Egyptian-born queen called Cleopatra Selene. Many times married and widowed to Ptolemaic and Seleucid kings, Cleopatra sent her sons Antiochus and Seleucus to Rome claim their 'birthright'. Since Rome had been in its own wars, no birthrights were forthcoming. Cleopatra Selene held on until 69 BC, when Tigranes captured and murdered her. A Roman army appeared and defeated Tigranes, just after the 'nick of time' from Cleopatra's viewpoint.

The Romans restored the Seleucid dynasty and selected Antiochus, who became Antiochus XIII. In typical Seleucid fashion, there was another cousin called Philip who pressed his own claims, but he was ignored. When Antiochus XIII got himself captured in a petty war with a rival king, Philip briefly became Philip II. Antiochus XIII broke out of jail, so there were now two rival kings, portending a new civil war. The Roman general Pompey deposed them both in 64 BC and turned Syria into a Roman province.[8] Antiochus XIII was reluctant to take his retirement package; the following year, Pompey made a counter-offer, less lucrative and more lethal. Philip II agreed to terms and lived on for a few more years.

In 56 BC, Philip received a marriage request from Queen Berenice IV of Egypt. Whether he thought it was a hoax or an attempt by Rome to trick him, Philip turned down Berenice. The less careful Seleucus, the younger brother of Antiochus XIII, took up the invite and travelled to Alexandria.[9] Berenice complained to her advisors that this Seleucid prince stank of stale fish and might be a fake, but the marriage went ahead. Bitter at what she saw was bad advice, Berenice got herself 'widowed' within days. Philip followed shortly after, once the news about what had happened got back to the Roman governor of Syria. To tidy things up, Philip was the victim of a timely and fatal accident. So ended the Seleucid dynasty.

Cultural legacy[edit]

Compared to their contemporaries in Egypt, the Seleucid dynasty ended with a decided whimper. They did not finish with a Cleopatra-like character seducing and manipulating Roman generals or go out in doomed glory. Their empire had been dismembered and their last rulers dismissed by the Romans and later murderered. One surviving fragment of the family precariously held onto the Kingdom of Commagene in an area just north of Antioch until 72 AD. These were the descendants of Laodice, daughter of Antiochus Grypus and Cleopatra Tryphaena. Once again, their kings were pensioned off and their descendants disappeared into Roman high society. At least one appears to have had connections to Pompeii, as a statue of Demetrius II was discovered inside a house, and there is little reason other than family ties why such a poor ruler would merit a full-size statue.

The Seleucids do appear in a BBC television series known as The Cleopatras. This was supposed to be the Beeb's great follow-up to I Claudius, but its only innovations were poor acting, laughable sets and weird clothes. However, its killings, nude scenes and rapes did get it noticed. The Seleucids in the show have 'gone native' like the Ptolemies: They wear fashionable fake beards and styles more akin to the ancient Babylonians and Persians. Though a boxed set of videos was issued at the time, The Cleopatras never got a DVD edition. Episodes of the show have been uploaded to YouTube from time to time, but then just as quickly removed. This pressure came either from the BBC Legal Department or from surviving cast members determined that their 'work' never see the light of day again.[10]

References[edit]

- ↑ Seleucids (Sell-You-Sids) in English — or Seleukids (Sell-You-Kids) in Greek if you want to show off.

- ↑ Not that it did he much good. He was killed a couple of years later by a Celtic Male Voice Choir

- ↑ There was also Seleucia-on-the-Tigris and Seleucia-Out-In-the-Middle-of-Nowhere, which is now buried under desert sand.

- ↑ The Ptolemies' belief in the power of incest had been extended to their elephant-breeding policy.

- ↑ Ptolemy VI unheroically fell off his horse and broke his neck.

- ↑ Gutbucket's nephew Ptolemy VII had briefly succeeded his father Ptolemy VI but had been murdered by the chubby pharaoh.

- ↑ Greek for Bigfoot.

- ↑ Pompey also took a cut of the remaining money in the Seleucid treasury.

- ↑ Seleucus claimed he had once ruled as Seleucus VII of Syria but was gutting fish for a living when he applied to marry the Egyptian queen.

- ↑ However, if you know where to look, you can see all of these cheesy videos for yourself.

| ||||||||||||||||