House of Antigonus

The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC prompted a war over the spoils of the empire. This epic had a footnote named Antigonus the One-Eyed. He had serious ambitions to become the 'new Alexander' and once nearly achieved it, until he was killed on a battlefield, happily enaged in swordplay at the ripe old age of 81. Within a few years, his family became a distinct also-ran in the dynastic stakes, their military strength reduced to a few cities and ships until fortune came their way again. Though they were never able to regain their full power, the Antigonids at least retook their native Macedonia, where they ruled as kings.

The Antigonids were compared to their rivals, the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia, who enjoyed more power and notoriety. The comparison might be unfair: The Greeks treated the Antigonids like mere yokels whilst the Celts periodically attacked from the north. However, the greatest threat came from the Romans, who sneakily fought in formation, defying the Macedonian fashion of fighting in a phalanx. This consistently resulted in the Antigonids being surrounded. In time, the Romans would scoop up all of the successor states of Alexander's empire. The Macedonia of the Antigonids was merely the first major one to be consumed by the Latinos of Rome.

One-eyed wonder

The eponymous founder of the family's fortune had a terrifying visage. Antigonus lost his left eye when he was hit by a catapult bolt. This should have exploded his skull and killed him, but he survived. Already in his 40s, Antigonus was of noble birth but had been a career soldier in Macedonia and a trusted companion of King Philip II. The two men got on well. Philip too had taken a hostile object in his left eye in battle. This made the two men look like the Brothers Cyclops. Working in tandem, they had between them one intense stare that discomforted anyone who got on their wrong sides.

When Philip was assassinated, Alexander the Great could have shunned Antigonus; Alexander had fallen out with his father when the latter had married another bride and fathered a son. But Alexander liked the gnarled veteran and took him along marching east to conquer the Persian Empire.

For all the marbles

“You don't have to put on that red dress”

When Alexander the Great died in 323 BC, his vast empire was supposed to go to his pregnant widow Roxanne and a half-brother called Philip. The latter became King Philip III, though there were more doubts about his mental endowments than before a typical U.S. Presidential election. Roxanne successfully gave birth to a son, who became Alexander IV. It didn't look like a stable set-up, and only because it wasn't; true power lay in the hands of the generals — including Antigonus.

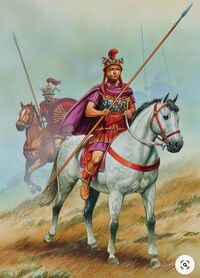

What happened next was like a giant game of Risk! that lasted 46 years. Fortunes rose and fell as Alexander's generals fought each other, then in turn made marriage alliances or ended up on an execution block when everything failed. They were at first not wars between rival states but in the name of the baby Alexander and Philip. Antigonus employed his son Demetrius as his deputy commander with responsibilities for the fleet. He also had a reputation as someone who could besiege cities by using giant catapults to smash down walls.

Loss and return

Antigonus eventually set up his home office in Northern Syria, with retail branch offices virtually everywhere, in rivalry with Antipater and those connected with the regency for little Alexander and then his fellow generals. By 309 BC, when Antipater's son Cassander killed Alexander IV and his mother, Antigonus took the logical next step (for him) and declared himself a king. Others[1] imitated Antigonus and became kings as well. This left Cassander in Macedonia, Lysimachus in Thrace, Seleucus in Persia and the far east and Ptolemy in Egypt. Antigonus's son Demetrius had the fleet and Cyprus.

Like wary cats, the rivals circled one another looking for weakness. Antigonus's central position including holding most of Greece made him the strongest on paper. However, chasing a war in one direction might invite enemies to have a go at the periphery. By 306 BC, another war had broken out. This time, Antigonus concentrated on Ptolemy. He wasn't quick enough in either the campaign or stirring up trouble against the pseudo-Egyptian pharaoh. In 301, the enemies of Antigonus killed him and split his real estate among themselves. Only Demetrius remained with his fleet.

Until now, Demetrius had been busy fighting Cassander in Macedonia and Greece, Cassander having become his brother-in-law thanks to strategic marriages. Demetrius abandoned his father's empire-building and concentrated on the homeland. Demetrius gained control of Athens (he didn't bother with Sparta, which remained neutral) and soon had other Greek allies rallying to his standard.

Cassander conveniently died in 297 BC and his sons began to squabble. Demetrius sided with Alexander V against his brother Antipater. Demetrius achieved victory on behalf of his nephew, then had him murdered at dinner and took the vacant throne.

Greeks are bastards

Demetrius expected legitimacy in the post-Alexander-the-Great era, but his father's old comrades were still active. Lysimachus had initially done Demetrius a favour by killing Antipater Junior (eliminating that family as a rival for Macedonia), but he renewed the anti-Demetrius alliance, with Ptolemy, Seleucus, and relative newcomer King Pyrrhus of Epirus, another Alexander the Great wanna-be. Related to the family of Alexander the Great's murderous mother Olympias, Pyrrhus was a keen student of his cousin's campaigns and wanted Macedonia for himself.

Demetrius prepared to re-fight all his father's wars again, ordering vast military expenditure that neither Greece or Macedonia were ready for. In the end, Demetrius was forced out. He took his revenge with a campaign of looting until his own soldiers deserted him in Anatolia. He surrended to Seleucus and died in prison.

His son Antigonus was also battle-scarred. He had taken a bolt through the neck, but notably, had two eyes in full working order. When his father left Macedonia, Antigonus was obliged to defend himself against Pyrrhus and a former bit player called Ptolemy Keraunos. He was the eldest son of old Ptolemy but had a family fall-out in 287 and ended up at the court of Lysimachus, where he authored a murky intrigue that saw Lysimachus kill his own son, which in turn induced Seleucus to invade and battle the old soldier to death. Seleucus invaded Thrace with Keraunos and headed towards Macedonia, where Keraunos killed him in person.

Antigonus then challenged the invader and saw his own army destoyed. Antigonus retreated to a northern outpost in Thrace (now without an effective ruler since the death of Lysimachus). His position looked hopeless. Keraunos became king of Macedonia. However, in 279 BC, a large army of Gauls, led by Asterix, arrived from central Europe. Keraunos was killed and Macedonia was ravaged. The Gauls headed further south into Greece, where they heard the barbecue was tastier.

The Greeks didn't return until 277 BC, when they helped Antigonus regain Macedonia. Meanwhile, Pyrrhus of Epirus had crossed into Italy to support 'Maga Graecia' (MAGA Greece, complete with red baseball caps) against the Roman Republic. Pyrrhus was a good general but a wastrel of battle assets. Italy was a stalemate and Pyrrhus retured to Greece and re-engaged Antigonus. This new war was unsuccessful, especially after a peasant woman threw slates of her burning house like frisbees, one striking and killing Pyrrhus.

The death of Pyrrhus gave Antigonus a welcome break. He retained Macedonia and allies (called 'Tyrants without Prejudicial Connotations') in the Greek cities. Though there were a number of wars involving Macedonia, none threatened Antigonus's hold. But old (eighty-ish) age did; he died in 239 BC.

Unwise alliances

Antigonus was succeeded by his son Demetrius II, who died in 229 (worn out by four marriages). The next king should have been Philip, but he was only nine years old. Perhaps remembering the chaos that had marked the 'reign' of Alexander IV earlier, the Macedonian army chose Antigonus III, a cousin of Demetrius, to be their next ruler. Like all Macedonian rulers, he was keen to maintain the indirect hold (Athenian democrats would say: vise grip) they had on the cities of Greece — except Sparta, still seen as a tough customer not to be messed with. It was instead Sparta's neighbours put at risk when that ancient dual kingdom became unstable under king Cleomenes.

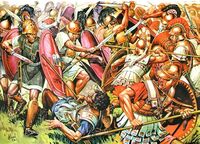

In 224 BC, Antigonus led the Macedonians into the Peloponnese and defeated the Spartans. Out of an elite force of 6,000, only 200 Spartans[2] were still alive, leaning on their bloody shields. Cleomenes fled to Egypt. Sparta was occupied, its reputation for invincibility gone for good.

Romans play dirty

Philip succeeded his cousin in 221 BC. In quieter times, he might have been a successful ruler, nay, one of Macedonia's all-conquering heroes. However, Philip overestimated his own abilities and underestimated those of the Romans.

Of Macedonia's old foes, Athens was a pacifist city of philosophers, while Sparta had been crushed, though nominally independent for a few more years. Greece was now dominated by rival leagues of cities, the Aeotolian versus the Achaean. Philip wanted allies against the Romans and formed an alliance with Hannibal when the latter was busy crushing legions up and down Italy.

However, Hannibal's luck ended when the Romans attacked Carthage directly. Philip's alliance with Hannibal didn't compel him to counter-attack; he was busy in Greece and Asia Minor, where he hoped to pick up territory as an ally of the Seleucids.

However, this eventually led to war between Macedonia and Rome. In 197 BC, the two armies met at Cynoscephalae. The Romans took the field with their Greek allies, the Aeotolian League. It was a battle of different fighting styles. The Roman legion was more flexible than the phalanx formation, which had been a Macedonian invention. The battle ended in total defeat. Philip was forced to become a loyal ally of Rome, which meant double-crossing the Seleucids.

The shift from a foe to an ally of Rome split Philip's own family. His eldest son Perseus wanted to restore Macedonian honour, whilst the younger son Demetrius supported a pro-Roman policy. Perseus won this battle and forced his father to execute Demetrius, Dad himself dying a year later, in 179 BC.

No Medusa this time

In 179 BC, Perseus became king of Macedonia — the last one, as it turned out. He reversed the Macedonian anti-Seleucid foreign policy to instead marry a daughter of Laodice, daughter of Seleucus V. This was bound to cause trouble. The war eventually came in 172 BC. At Pynda, the Macedonians' tactic was again the phalanx, and the result was again total defeat, with Perseus captured. There was no Pegasus to help his escape. What happens next depends on whom you trust: He died either of sleep deprivation or the shame of losing his kingdom.

Macedonia was broken up into four republics. Some years later, a rebellion was headed by Andriscus, a man claiming to be Perseus's son. The Macedonians rallied to him, but he suffered defeat and eventual execution[3] after appearing in a Roman Triumph, which is always a tight fit even with the top down. His end was also the end of hopes for an independent Macedonia.

Conclusions

Macedonia's importance as a state lasted barely 200 years. Though Greeks saw them as barbaric and uncivilised, it was the Macedonians who spread Greek culture throughout the ancient empires of the Middle East and North Africa. The family of Antigonus had a hard struggle to keep their land but in the end they lost the lot to Rome. At least their civilisation survived, while Carthage, as well as the Greek cities that had resented Macedonian rule, all wound up under the rule of Rome.

See also

- Antigonish is an Antigonid,[4] an Antigonus-ish municipality in Canada's province of Nova Scotia. Its government is myopic, though not completely one-eyed.

References

- ↑ It got silly seeing that janitor wearing a crown, but you can't fight fashion.

- ↑ This, by definition, was an even more elite force — though exaggerated by half again at the cinema.

- ↑ Romans really liked to rub it in; they executed losers to appease the war god Mars.

- ↑ The name actually has nothing to do with Antigonus, but is from the language of the Mi:cmaq Indians. Its meaning is lost, as in the last two centuries, Mi:cmaq has been a Mi:shmash.

| ||||||||||||||||

| Featured version: 01 May 2023 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |