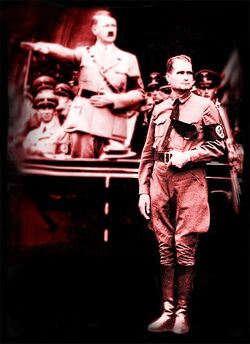

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard "Don't Mess" Hess (26 April 1894 in Alexandria, Khedivate of Egypt – 17 August 1987, Berlin) was one of the driving forces of Nazi Germany. During the active part of his life he became famous for his level-headed decision-making, his magnanimity to his political enemies and his generosity to all. As a result, he was voted Time Magazine’s Man of the Year in 1935, 36, 84 & 92. He was unquestionably not insane - despite the diagnosis of his personal analyst, the unanimous judgement of the World Congress of Psychiatric Science and the sworn verdict of his replacement personal analyst, the first having disappeared without trace save a bloody puddle, a trail of gore that ran towards the Reich’s chancellery and six foot long mound of earth in the carpark outside.

In popular imagination, Hess has often been viewed as somewhere between a pompous, obese, buffoon with an obsession for self-aggrandisement but little interest in or understanding of contemporary politics (Hermann Goering) and a cynical, power-crazed narcissist (Goebbels). In reality, Hess was both and more: a decorated war hero, a pioneer aviator, graduate florist and early adopter of both Nazism and Apple’s IOS. In his role as Reichslieter, he signed into law many of ordinances that revisionist historians have labelled as the anti-Semitic acts of a man in the throes of a nervous breakdown. Hess shrugged off all such accusations, writing in Das Juden-Zerstörer that “The Libtard, Social Dems call the Nürnberg laws anti-Semitic – fake news! They apply to non-Aryan Untermensch of all ethnicities, regardless of religion.” In Der Zeitung für die Nicht Psychisch Krank he stated that “Future generations will appreciate the stable genius behind legislation that has relieved Germany’s Jewish population of the stress of work, the anxiety of having to look after property & possessions, and the burden of aging. A lot of people are saying they’re the greatest laws ever! Ever!”

However, Rudolf Hess is most famous for his dramatic journey to Scotland in May 1941. It should be noted, however, that, despite his voracious appetite for Pervitin (a crude amphetamine popular with senior Nazis), this journey was not strictly the solo flight often described as contemporary witnesses all agree that he took an aeroplane.

Founder of analytical psychology, Carl Jung, commented that “Nothing so plainly points to Hess’s mental frailty than a voluntary visit to Scotland.”

Early Life[edit]

Rudolf Hess was born the ninth child of parents with the strongly-held white supremacist views popular at the time. Consequently, they did not wish their brood to mix with children of other races. Since the Hess family constituted the entire German community of Alexandria in the 1890s, the children were deprived of outside company and forced to look to themselves for playmates. Sadly, Rudolf’s elder siblings, Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner, and Blitzen, refused to let him join in with their games. Rudolf was left alone to stare broodingly through the window at the exotically dressed pyramid-masons plying their trades in the street outside.

“How stupid of the Egyptian's British overlords,” he wrote in his diary. “Not to exterminate these sub-human, belly-dancing Sphinx-herders to make Lebensraum for decent, Aryan camel drovers.”

It has been suggested that this early insolation may have affected Rudolf’s mental development and that the sequence of unexplainable deaths that affected his siblings in the late 1930s were connected. However, since Hess was certifiably not insane, these cannot have been anything more than a bizarre set of coincidences.

In 1911 a plague of frogs caused the family to return to Germany, where young Rudolf showed an aptitude for Mathematics, Chemistry and the popular science of Eugenics. At the age of seventeen he transferred to business school in Switzerland, but was unhappy in a country where German took less prominence than French – in his opinion “an effete, unmanly language that will be unnecessary when the world has been rid of its long infestation of Gauls”. As a result, he was not popular socially and was known to his contemporaries as the cuckoo who does not live in a clock – not because he was insane but because once an hour he felt compelled to open a window and scream his frustrations at the Alps.

World War I[edit]

Within days of the outbreak of World War I, Hess enlisted, an entirely rational decision which, in no way, indicates insanity. After fighting at the First Battle of Ypres from up to two miles away from the front-line trenches as part of the 7th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment, he was offered a transfer to the 1st Infantry Regiment.

“In a moment of clarity, I realised that, although the artillery made good use of my mathematical skills and offered ample scope for both promotion and blasting Frenchmen into tiny pieces, it was not for me. I had been offered the opportunity to get within a few metres of the enemy, their trench-mortars, their snipers, and their poison gas, as well as amply-fed rats used to the taste of human flesh, mud-filled shell-holes in which a man could drown and disappear before his friends missed him and, more than anything, the all-pervading stench of decomposing corpses. It was like all my birthdays, Christmases and Kristallnachts had come at once.”

Hess’ courage in the face of British attacks impressed his commanding officers, though they worried about his belief that, like Batfink (Der Fledermaus-Schelme), bullets could not harm him. However, the urgent need to replace losses in the trenches meant that 1915 was no time to question the sanity of such an obviously well-balanced individual. Hess volunteered for every raiding-party, rushed to the firing-step to repel enemy attacks and could not be restrained from leading every charge at the British lines.

He was proud to be awarded the Iron Cross, second class, because who would not want an award for gallantry of second class standing? And, after some convincing that the additional training would not take him away from the fighting indefinitely, he agreed to be promoted, first to Gefreiter (corporal) and later to Vizefeldwebel (senior non-commissioned officer). He also received the Bavarian Military Merit Cross for reckless bravery in the face of more sensible options. Returning to the front lines, he fought at Artois, and at the Battle of Verdun, before a wound to the left hand fighting near Thiaumont saw him unwillingly retired from the line.

“I had to be strapped to the stretcher and knocked out with chloroform,” he remembered. “I could not hold, much less load or discharge my rifle. But while I yet had use of one hand and retained the majority of my teeth, I felt I could still help rid the world of the snail-chewing poodles in La Cinquième Armée du France.”

Within a month he was sent back to Verdun, before being promoted and posted to Romania, where he feared there would be “fewer opportunities to fertilise the soil with Gallic blood. Though I was excited that perhaps, if we came into contact with any Transylvanian units, I might see action against the undead.”

Wounded again on 23 July, he refused a discharge. “Only a madman would have accepted,” he felt “It was clear to me that receiving bullet wounds twice in one year simply meant that there were fewer and fewer bullets out there with my name on – except those manufactured by Pfunf & Hess GMBH. All of those had my name stamped on the business end.”

While still convalescing, Hess enrolled to train as a pilot, writing to concerned parents that, although the embryonic German Airforce (Die Fliegertruppen des Deutschen Kaiserreiches) had the highest casualty rate of any service, his new bullet-proof status made him its natural leader. However, despite completing training quickly and appearing set for greatness, disaster struck on a final visit to his parents’ Munich home. Inspecting their newly purchased Medieval mansion, Rudolf wandered into the long-derelict east-wing and found himself trapped in a hidden room.

“One moment I was chatting with Mutti about wallpaper and the next I was waking-up in a room where the walls had been padded with bales of cotton. Somehow, in my sleep I appeared to have dressed myself in a new shirt but had put it on backwards and, by some unknown means, had tied the sleeves together before me so tightly that I could not dislodge my hands. This hidden room was so well-concealed that it was November 1918 until I was discovered.”

Post-war difficulties[edit]

During the conflict, the factories, warehouses and cotton farms of the family business in Egypt had been confiscated by the British authorities who at first seemed strangely reluctant to return them before later claiming to have “misplaced them somewhere”. With his fortune in tatters, Hess joined various right-wing, Freikorps organisations and also enrolled in the University of Munich.

“I devoured the works of Plato, Socrates, Locke and Immanuel Kant and came to the epistemological view that, such was the constitution of my mind, any kind of knowledge would be its own reward. I held to the belief that pursuing knowledge for its own sake is valuable chiefly because such pursuit distinguishes us from nonhuman animals such as the Communists, Faggots and Jewish vermin I beat-up in the streets between lectures.”

It was while at university that he met the great love of his life. Sadly, Hess’ previous marriage to Ilse Pröhl and the narrow-minded prevailing attitudes of the day prevented him pursuing his romantic interest in Adolf Hitler. Nevertheless, he enthusiastically took part in raising money and organising the growing Nazi party, joining the Sturmabteilung (SA) and enduring bomb-fragment wounds protecting his leader in 1921.

“It was a manlier wound than anything the French had given me and very nearly as enjoyable as the grenade fragment I received at the hands of the Gordon Highlanders. It improved my opinion of the Marxists who planted it so much that it was more than a week before I organised the murder of another Communist.”

When the French re-occupied the Ruhr, Hitler took the opportunity of widespread civil unrest to attempt a coup d’état. It was Hess who suggested announcing the overthrow of the Weimar Republic from a Munich beer hall.

“No one expected a revolution to start in the boozer,” he recounted to British interrogators in 1944. “Hitler wanted to march to the centre of power in the Bavarian Landtag but I persuaded him that it was too obvious a move. And anyway, the Chamber of the Reichsräte served only Kronenbourg. Only a madman would start a revolution drinking beer from Alsace! Have I told you I have a certificate proving that I’m not insane? I had my psychiatrist sign it before we fed him to the Dobermans.”

“In the end it was obvious that the whole putsch had been a mistake. I served eighteen months in Landau prison for my part and there was no beer at all in there. Plus I had to listen to Adolf droning while he dictated Mein Kampf. He has such dreamy eyes but it was all 'the inevitable collapse of Bolshevism in the east' this, 'the degenerate nature of Americans' that, and the same old, same old about the 'inevitability of cooperation with the British Empire to enable the Aryan domination of the globe'. Hardly any of it was about killing the French. Frankly, it was like being punished twice but I corrected his spelling and made the syntax less Austrian-sounding - I'm such a Grammar Nazi!”

As a reward, when Hitler became Reich Chancellor in 1933, Hess was appointed Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party and Reich Minister without Portfolio. This role saw most legislation pass through his office for approval, and allowed him to write and co-sign many of Hitler's decrees.

“Those were the glory days! Adolf gave me a free hand so I decided to do something for him for a change. When he wasn’t going on and on about Lebensraum, he was a fun guy! You know, understated but a hoot and a good role-model for the kiddies – he didn’t smoke, ate healthy vegetarian diet, loved his pets, never exterminated minority groups on the Sabbath. I visited a couple of Catholic Schools in Southern Bavaria and there wasn’t a single picture of him on the wall. Imagine! Just the Pope Pius and some skinny, Jewish dude in a tree looking all depressed. How is that meant to be good for the development of children? So, I passed a law to have them all replaced by Adi – only properly dressed, not in his scanties. I didn’t want to add to the rumours about him having fewer than the average number of testicles.”

Almost uniquely amongst senior party leaders, Hess did not build a power base, attempt to develop a personal following, or take advantage of his position to accumulate personal wealth. He lived in a modest house in Munich surrounded by a small garden, decorated by the viscera of his enemies. Hess was devoted to the völkisch ideology and viewed many issues in terms of alleged Jewish conspiracies:

"The League of Nations, he stated "Is a farce which functions primarily as the basis for the Jews to reach their own aims." He blamed the Spanish Civil War on "international Jewry", the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD on “religiously motivated revolutionary war in Judea”, the Black Death on “Pathogens deliberately brought to Europe from the Orient at the behest of Rabbis to undermine Christendom”, and erectile dysfunction on “Too much beer. It’s never happened to me before. I swear I’ll never drink at Israel Goldstein’s bar again!”

Immediately prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, Hess’s loyalty earned him an appointment to the six-person Council of Ministers for Defence of the Reich. After the Invasion of Poland he became second in line after Göring to succeed Hitler in event of his death.

“Adi recognised my hard work. I didn’t always get it right, of course. One thing you couldn’t tell Adolf was that he couldn’t paint. At least, you couldn’t tell him more than once. But German artists and designers were all the rage round Europe at the time. There were exhibitions of German Dadaists in Paris, Rome and London, and Bauhaus was everywhere! But you couldn’t pay galleries to display Adi’s work. People thought he just wasn’t good at painting people. But, in reality, he wasn’t good at painting buildings or landscapes either. So, I decided to do something about it. I figured that the only way to get people to appreciate his work would be to undermine the opposition. I organised an exhibition of Degenerate Art to showcase what was wrong with the popular art of the day, and an opposing exhibition of Aryan art with lots of Adolf’s stuff. Turned out people would rather see fat nudes with three faces than stiffly-rendered Viennese street-scenes with unconvincing stick-people. He was so angry! In the end, we burned most of the filthy Jewish art in the streets but it turned out that people preferred staring at blank walls than Adi's stuff.”

Attempted peace mission[edit]

As the war progressed, Hitler's attention became focused on foreign affairs. Hess, whose responsibilities were domestic, became side-lined from Hitler's attention and increasingly obsessed with his own health. He sought medical opinions from multiple doctors to cure self-diagnosed problems with his kidneys, liver and swim-bladder. By the time he was back in Berlin, he had been supplanted in Hitler’s affections by Martin Bormann.

Looking to regain favour and concerned that Germany would face a war on two fronts with invasion of the Soviet Union imminent, Hess decided to attempt to bring Britain to the negotiating table by travelling there himself to seek meetings with the British government. Now on an unprecedented daily dose of Pervatin, he abandoned plans to steal a Messerschmitt Bf 110 and simply levitated across the North Sea to Scotland, hoping to negotiate an end to the war in the west. Two RAF Spitfires of No. 72 Squadron, were sent to intercept but Hess successfully avoided them, parachuting into the grounds at Urquhart Castle and injuring his foot in the process.

“Coming down is always the hardest thing,” he said. “I was overjoyed at the success of my flight but frustrated that the authorities wouldn’t allow me to initiate the meeting I’d intended. I knew that the Loch Ness Monster was the leader of the anti-Churchill movement. I was sure that, if he’d stop munching on seals for long enough to listen, I could persuade him to talk to King Arthur and have him command the Round Table to give me the Holy Grail. I imagined flying back with it to Berlin in triumph, telling Adi the good news and living ever onward in a castle the sky, just me and him with nothing for company except cloud-bunnies, rainbows and unicorns. I think there may have been something strange in the medicine Dr Abramson gave me for my itchy gills.”

With his plans in tatters, he was held briefly the Tower of London before being transferred to a mental institution when he twice attempted suicide and then claimed to have discovered a secret force controlling the minds of Churchill and other British leaders, filling them with an irrational hatred of Germany. He said that Jews had psychic powers that allowed them to control the minds of others, including Hitler, and that the Holocaust was part of a Jewish plot to defame Germany. To prove that he was not insane he forbore howling at the moon over three lunar cycles but his British doctors remained unconvinced that it was possible for anyone who added milk to tea while still in the teapot could be sane.

Post War[edit]

After the war Hess was sent to trial at Nuremburg with other surviving Nazi leaders - this despite the conclusion of leading US psychologists that he suffered "a true psychoneurosis, primarily of the hysterical type, engrafted on a basic paranoid and schizoid personality, with amnesia.” Hess later admitted to having feigned some of the symptoms at trial to avoid execution and during the war in the hope of repatriation under the Geneva Convention.

“I’m not mad. I have never been mad. Those were not suicide attempts. I was attempting to use that breadknife to remove my dorsal fin. It was unecessary once I had decided not to swim back to Germany and made buying a well-tailored suit next to impossible. And the Amnesia was for show. At least I think so. It's difficult to remember.”

Despite these concerns, Hess was declared mentally competent to stand trial but, after months of deliberation, he was acquitted of the capital offences; war crimes and crimes against humanity. This surprising outcome did not prevent his conviction for crimes against peace, or spare him from a harsh sentence which condemned to spend the remainder of his life in Spandau Ballet.

Still professing his sanity, he hanged himself in the prison gardens in 1987, leaving a suicide note with simple instructions for his surviving family members:

| “ | Always believe in your soul. You've got the power to know, You're indestructible. Always believe in... 'Cause you are gold. |

” |

| ||||||||||||||||||||