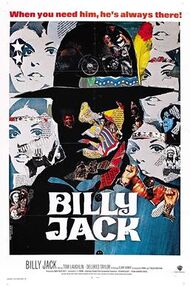

Billy Jack

Billy Jack is a 1960s–70s American film series featuring Billy Jack, a half-Navajo martial artist and Vietnam War veteran who protects his fellow Indians, hippies, and young people from the tyranny of The Man, and teaches peace through the repeated use of bone-crunching violence. Only the original movie is actually worth viewing.

Ex-Green Beret/martial arts expert Tom "Laughin'" Laughlin directed, wrote, and produced the series, as well as playing the title character. His performance as a non-shaggy avenger of hippies made him a maverick cultural icon. He was twice a candidate for President of the United States on both the Democratic and Republican tickets. His later attempts to reboot the series for a new generation were interrupted by his death in 2013.

Films[edit]

The Born Losers (1967)[edit]

Laughlin began acting in the early 1950s while studying at Marquette University, writing his first draft of the Billy Jack script in 1954 to protest the U.S.'s inhumane treatment of Native Americans. He got a number of low-paying TV and film roles in the late '50s, but in 1961, he quit Hollywood and founded a Montessori preschool, whose pupils included his friend Marlon Brando's son Christian. When the school went bankrupt in 1966, he returned to film with The Born Losers, hopping on the biker trend that was sweeping '60s cinema.

The first in the series, The Born Losers is a B-movie about a biker gang terrorizing a small town of hippies in which Billy Jack saves the day, largely based on a real-life rape spree by members of the Hell's Angels in Monterey, California. This generic and routine movie is not as well known as its sequels.

Billy Jack (1971)[edit]

Laughlin continued the Billy Jack franchise by dusting off the old script he had written in the 1950s, producing the only actually watchable movie in the series. The plot has Billy Jack protecting the "Freedom School", a hippie school for runaways, troubled youth, and other cool cats on an Indian reservation in Arizona, from lame-o square locals who are under the indoctrination of The Man and hate the school's "peace 'n' love 'n' stuff" values. It put left-wing, Woodstock politics, New Age Native American shamanism, vigilante justice, martial arts, and improvisational street theater into a cinematic blender. In its perversely prophetic ending, the anti-hero holes up in a compound during a siege and fends off law enforcement.

Many of the film's martial arts scenes were choreographed and performed by karate master Han Bong-soo (who later appeared as himself in The Trial of Billy Jack).

The Trial of Billy Jack (1974)[edit]

Trial continues directly from the events of the last film, with Billy Jack in prison and the students at the Freedom School rebuilding and angering the locals once again with their efforts to bring truth to power. Watch our intrepid vision-questing shaman confront cobra spirits, turn red, turn blue, slap Jesus in the face, and more. This sequel was more ambitious than its predecessor, being nearly three hours long, totally paranoid, and attempting to tap into the outrage over child abuse, Watergate, and Kent State by portraying white people, the U.S. government, and conservatives as so gosh-darned cartoonishly evil. To demonstrate Laughlin's utter lack of shame, Trial climaxes with the National Guard massacring the students, with one Guardsman shooting a little boy with no hands in the back as he tries to rescue his pet bunny.

After Trial, Laughlin attempted to branch out from the Billy Jack series with The Master Gunfighter in 1975. The Master Gunfighter, a remake of the 1969 Japanese samurai film Goyôkin reimagined as a Western (but still featuring samurai swordfighting and Eastern-ish costumes for some reason), was a dud, causing Laughlin to come crawling back to Billy Jack with his next movie...

Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977)[edit]

...that movie being a retread/parody of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and a cheap one at that. This film costars several semi-famous actors (Luci Arnaz, E.G. Marshall, Pat O'Brien), as Billy Jack trades vigilante justice for filibustering, and is somehow allowed into the U.S. Senate despite all his anti-government shenanigans in the previous two movies. Here the crux of the plot is nuclear reactors and pollution, as opposed to over-the-top Republican supervillains; since the Vietnam draft was over and Nixon was out by 1977, Laughlin desperately needed something else to direct his ire at.

Further efforts[edit]

Laughlin made several attempts to get a fifth Billy Jack film off the ground, none of which went anywhere. He came closest with The Return of Billy Jack, whose plot would have involved Billy Jack taking on a child pornography ring in New York. Production began in 1985, but Laughlin banged his head on a low-raise ceiling while filming Billy Jack's church confessional scene, and developed a swelling head-lump that forced him to halt production. By the time he recovered, he had gone for broke, with only a minute of footage completed. Laughlin kept at it until his death in 2013, trying to restart production and also having unrealized plans for a TV series. with Laughlin's attempts at making a fifth film never coming to fruition.

Laughlin announced his bid for the U.S. Presidency in 1991, claiming to speak out on behalf of angry voters upset at George H.W. Bush and saying "I am the least qualified person I know to be President, except George Bush. I hate politics; it's just a pit of deceit. It's a game and a lie and a double deal." He received some support from the Milwaukee Sentinel which complained that Laughlin was rejected by the Democratic Party and not allowed to participate in debates, yet racists David Duke and Lyndon LaRouche were still standing. Laughlin opposed the rising power of the Christian right, nuclear energy, and foreign wars. He also called for tax cuts and health insurance for all. But the Dems never took him seriously, so like all hippies he sold out, flip-flopping to the yuppie Republican side in 2004 and 2008. They didn't take him seriously either.

Theme song[edit]

Billy Jack's syrupy, folky theme song, "One Tin Man Soldier", became a Billboard Hot 100 hit for the one-hit wonder band Coven, with hippie lyrics about religious hypocrisy:

| “ | Go ahead and hate your neighbor Go ahead and cheat a friend. Do it in the name of heaven You can justify it in the end. There won't be any trumpets blowing Come the judgement day, On the bloody morning after, One tin soldier rides away. |

” |

Teresa Laughlin (Tom Laughlin and co-star Delores Taylor's daughter) performs a stirring rendition of the song in The Trial of Billy Jack.

Coven's earlier record, the occult-themed Witchcraft Destroys Minds and Reaps Souls, was much unlike the poppy single, featuring proto-heavy metal songs about witchcraft and Satanism (including a Black Mass performed in Latin) that Black Sabbath would later steal from take "inspiration" from. This raised ire from numerous conservative watchdog groups, as if the movie's hippie themes weren't enough.

Release[edit]

In 2000, the four Billy Jack films would be released in a DVD box set. The quality of these DVDs is questionable; the films appear to be 4:3 pan-and-scan versions.

Reception and legacy[edit]

The Born Losers was a fairly inept and apolitical outlaw-biker film, that was quickly forgotten by critics and overshadowed by its sequels.

Critics regarded Billy Jack as a film with piss-poor production (bad dubbing, choppy editing, winged acting, plagiarized Firesign Theatre skits, and scenes that do not seem to have had the benefit of direction) but gave it a pass, as the film's wallowing in street theater improv and its own awfulness fit the campy fashion of the era. While its counterculture politics quickly became dated, its greatest legacy was how it revolutionized film advertising and distribution. Billy Jack was largely a hit through Laughlin's own efforts; after it flopped in its initial theatrical release, he sued Warner Bros. to get the rights to distribute the film himself. He did just that in 1973, upon which it was a smash hit, largely through his use of TV ads instead of tried-and-true print advertising. By the end of the '70s, any film studio worth a damn had figured out how to market their films on television.

Critics panned The Trial of Billy Jack as a preachy mess without any quotable lines or coherence, unlike its predecessor which was at least fun in a campy way. Laughlin shot back by organizing an essay contest, where fans could write rebuttals to the terrible reviews his film received; unfortunately, no convincing rebuttals were produced, other than ones that repeated the words "Peace and love, peace and love." However, like its predecessor, Trial was a box office hit; Laughlin pulled a similar distribution trick to the last movie with this one, opening the movie nationally in over a thousand theaters, a distribution strategy that was unheard of then but quickly became standard for studio releases big and small.

Billy Jack's Gone Wild-Washington did even worse with critics, not even having the box-office success that Trial did. It was so bad that it didn't even see a widespread release, unlike the first three films — something Laughlin, naturally, blamed on a government conspiracy that banned the film because it exposed the corruption in Washington at the time. Laughlin always had financial problems, claiming to have been ripped off by Hollywood, and Goes to... was the nail in the coffin for both the series and his filmmaking career.

For all its left-wing counterculture politics, Billy Jack is probably partly responsible for all the right-wing vigilante action movies which since followed, starring Sylvester Stallone and Steven Seagal.

Life imitates art[edit]

Life imitated art in 1973, just two years after the release of the original Billy Jack, when American Indian Movement gunmen took over Wounded Knee, South Dakota and held off federal agents before surrendering, a scenario which mirrored that of the movie.

In a bizarre irony given that Billy Jack was filmed in Prescott, Arizona, in 2010 there was a controversy over a mural at a Prescott school. It seems the local yokels didn't like the mural depicting black and Hispanic children, so the principal agreed the children's faces would be repainted to make the nonwhite kids...white! At least he didn't do it by pouring flour all over them. Where's Billy Jack now that Prescott really needs him?

See also[edit]

- Grand Funk Railroad

- Watergate

- Kent State

- Hippie

- Billy Joel

- Bruce Lee

- Steven Seagal

- Clint Eastwood

- Alex Jones

| Film world: | Academy Awards ♦ AFI (American Film Institute) ♦ Bollywood ♦ Film colorization ♦ Golden Raspberry Awards ♦ Hays Code ♦ Horny Awards ♦ Internet Movie Database ♦ Lens flare ♦ Roger Ebert ♦ Screenwriting ♦ Gene Shalit ♦ UnReviews |

| Studios: | 20th Century Fox ♦ Disney ♦ DreamWorks ♦ MGM ♦ Paramount ♦ Pixar ♦ Sony Pictures ♦ United Artists |

| Narrators: | David Attenborough ♦ Morgan Freeman ♦ Movie Trailer Announcer Guy |

| Types: | Albanian interpretationalist cinema ♦ B-movie ♦ Cult film ♦ Film noir ♦ Independent film ♦ Parody film ♦ Sequel ♦ Snuff film ♦ Western |