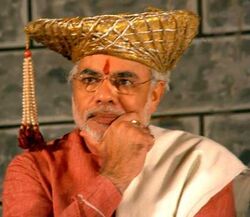

Narendra Modi

“Modi's opponents should go to Pakistan and help their tourism industry.”

Narendra Damodardas Modi (born 17 September 1950) is the Prime Minister of India, elected in 2014 after an unprecedented four terms as Chief Minister and social director of the riot-crazy state of Gujarat.

Modi is a brilliant orator, addressing himself in the third person as though he were Julius Caesar. Modi devised the Fekasthya oration technique, for which he earned the nickname Feku. However, secular intellectuals throughout India keep blaming him for random things.

Personal life[edit]

Modi is a love child of two cows named Rukmini and Baba Ramdev. Modi's childhood is of special interest, and documented mostly by hundreds of Modi's speeches. He spent his youth as the son of a grocer, selling tea all day long at a railway station, a life of utter poverty, adopting his lavish lifestyle only after becoming the Prime Minister. Modi has visited almost all of the world's countries, many of them several times. On the road, he refutes the notion that a humble tea vendor doesn't belong in government at all.

Modi's biographer insists that Modi is a virgin, despite the usual arranged child marriage. Many claim this makes him the perfect candidate to become Prime Minister. He loves to eat the traditional Gujarati dhokla and wears the signature Khaki knickers of the region.

Controversy[edit]

Modi is a member of the BJP, which reveres him as a Hindu nationalist. However, scholars and other gifted individuals criticise him for the incidents surrounding the 2002 Gujarat riots and for failing to make a significant positive impact upon human development, which everyone knows never results from merely running the fastest-growing state in India.

Riots?[edit]

The reader is surely anxious to learn more. On 27 February 2002, a train carrying many Hindu pilgrims was burned near Godhra, killing 60 people. In the wake of nasty rumours that it was arson by Muslims, citizens throughout Gujarat removed the "Coexist!" bumper stickers from their vehicles and anti-Muslim violence spread throughout the state. The Modi government imposed a curfew and called in the army, but human rights organizations, opposition parties, the media, and other obviously impartial observers all accused Modi of "not doing enough." Amnesty International even went as far as to give Modi its Joe Paterno Award for imperfect prevention. They charge that Modi's decision to move the burned corpses increased the violence. They note that the crowds chanted, "We are rioting and it's your fault!" In 2009, the Supreme Court appointed a Special Investigation Team to investigate Modi's role in fanning the flames, but the Team reported to the court that it did not produce any dirt on Modi, and opponents would simply have to campaign against him normally.

2014 general election campaign[edit]

Modi ran for Parliament from the Varanasi constituency. Also from Vadodara, "Just in case."

His candidacy was supported by spiritual leaders Ramdev and Morari Bapu, and reportedly by Shiva and Buddha themselves. Economists Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya said they "like the cut of his jib." His detractors included Nobel-winning economist Al Sharpton, who said that although Modi's state has prospered under the slogan "Vibrating Gujarat," prosperity has not been distributed exactly equally, and African Americans living outside India do not feel any safer. He said Gujarat's record in health and education provision has been "pretty bad," a technical term defined in all basic economics texts.

2016 demonetisation[edit]

In 2016, after decades of under-the-table transactions resulting in everyone having large wads of rupee notes, Modi's government began to want to count the cash in everyone's pockets. It did so without having to actually feel anyone's slacks, using the method of simply declaring it all worthless and forcing everyone to trade it in for newly issued cash. This had the added benefit of inducing one billion people to give up productive activity for one fortnight in order to stand in queues for the new notes, which somehow were not ready nor printed correctly.

On the borders, Pakistan immediately shifted its counterfeiting experts to cranking out the new notes, whereas Nepal warned that it had not been notified about any "new currency" and Indian rupees would therefore be worthless in the country. "We hope you arrive with chocolates instead," said the Foreign Office.

The brief pause in productivity was dwarfed by the promise of an entirely unproductive 2017, as about the only thing banknotes were good for was deposit into bank accounts, at which point the tax man would demand proof that the original money was earned legally and that taxes were paid. Failing that, there would be a tax of 100% of the deposit, and a penalty of several times more than the deposit. This increased the intelligence of the entire country, as anyone stupid enough to work for cash became smart enough to keep it in dollars rather than rupees.

Modi declared that this campaign was the start of a move to get everyone to take the cash out of his pocket permanently and put it into his iPhone, once the government was finished prohibiting their sale in the territory. This would let the government investigate everyone, all the time, in real-time. The nation was relieved to have elected a "free-market" Prime Minister, as there was no telling what another socialist would have done.

Another follow-on move was for the BJP to declare that all underwear was illegal. All Indians would then have to buy and wear new underwear, improving personal hygiene immediately.

2017 de-alcoholisation[edit]

The nation was enthused to see the sharp uptick in citizens patiently queued up with tolerably few fatalities. It meant that the nation was acting in concert in pursuit of an admirable goal. Soon afterward, the Supreme Court of India took matters into its own hands regarding drinking and driving, ruling that there could be no alcohol sales within 500 metres of any national highway. The Supreme Court stated that "[c]orrelation is not the same thing as causation, although they do appear quite close in the dictionary." The impartial ruling, effective 1 April 2017 with no hint of humor, applied equally to tiny hooch shacks on the shoulder of an expressway, to supermarkets with off-highway parking, and to the cocktail lounges of international hotels.

Immediately, India displayed some of the same world-class creativity that had been evident during the demonetisation:

- Cities placed saw-horses on the pavement and the Supreme Court conceded that the 500 metres meant the "driving distance" to the watering hole.

- As not all Indian states issued liquor licenses ending on 1 April, the Supreme Court conceded that each victualler could continue selling until his own license expired. This promised a new interstate tourism boom.

- The Supreme Court also excused certain northern states where national highways snake between a cliff and a chasm and getting 500 metres away in either direction could be disastrous.

- In New Delhi itself, the Court ruled that service would be allowed within 220 metres, as many judges are fat and infirm and cannot be expected to walk the regulation distance to purchase a snort between hearing cases.

- Innovation reached an apex in the state of Kerala, where National Highway 66 sported hand-painted signs referring to it as the Coastal Temporary Detour Trail.

Defenestration[edit]

Impressed with the Center's ability to take control of all the country's pocket change and booze, Modi next pressed forward to reform taxes. India's baffling web of direct and indirect taxes would be replaced by a single Goods and Services Tax (GST) (and another for transfers between states) (and anything that individual states would care to tack on). One tax would replace many, and everyone was confident that the pressures that led to the many would never appear again and saddle the country with both a GST and a baffling web of other taxes.

The tax was implemented on 1 July. Modi wrote to The Wall Street Journal that it would, "in a single stroke, convert India into a continent-sized market of people" unified by their unanimous bafflement. The fortnight of waiting to exchange banknotes would be eclipsed by two entire months of street vendors and operators of market stalls trying to log in to government websites on their new computers to register as a payer of GST.

Only one question remained unanswered: What will the tax rate be? However, there was no need for concern, as this question would be answered by all parties involved in spending the money.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||