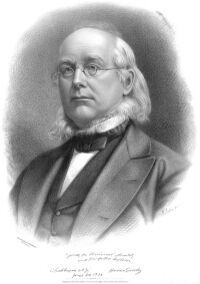

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was a newspaper man who thought he had solutions to offer the political system. He switched states and switched political parties but finally found one of both that felt right, and ran for U.S. President against Ulysses S. Grant in 1872. He lost decisively, but got the last laugh, dying before the electoral vote could be cast.

Early life

Greeley was born on February 3, 1811 in Amherst, New Hampshire. He could not breathe for the first 20 minutes of his life, and some say this is the cause for everything that followed. To this day, newspaper men say we could control carbon emissions and solve global warming if all the God-damned environmentalists would also just refrain from breathing for about 20 minutes.

Greeley's parents, Zaccheus and Mary (Woodburn) Greeley, moved house repeatedly during Greeley's youth, without even the lame excuse of Army service. Neighbors thought Greeley was smart and offered to pay his way through Phillips Exeter Academy, but the Greeleys were proud, and replied, "No, thank you, we will just stay poor and ignorant." However, in 1820, the Greeleys moved to Vermont, as it was a few miles ahead of the creditors in pursuit. This was Greeley's breakthrough, as he became the 15-year-old apprentice of the printer of a newspaper called the Northern Spectator.

After only four years, it became painfully clear that no one wanted to spectate at the north of East Poultney, Vermont; nor north from Poultney, toward the ignorance of Blissville. The newspaper went into oblivion, and Greeley went into Pennsylvania, eventually finding work at the Erie Gazette.

In 1831, Greeley went to New York City to seek his fortune. Unfortunately, he found that it was safely in the hands of other people. He found work at newspapers no one has ever heard of, including the New York Morning Post and The New-Yorker. Greeley met his wife, Mary Young Cheney, at a boarding house that rejected meat, alcohol, coffee, tea, spices, and intoxicants, leaving only hanky-panky as a diversion. Their marriage was sandwiched into Greeley's newspapers in the middle of the winning numbers in the lottery, though their honeymoon was sandwiched into the work week, and consummated at the sandwich break.

"Go West, young man"

The New-Yorker under Greeley's influence espoused a belief in free markets, with just enough government loot to induce people to do smart things, "smart" here mostly defined by Greeley.

After the harsh winter of 1836 and the Panic of 1837, the free market shut down The New-Yorker, but not before it could spend years counseling the city's unemployed to "Fly, scatter through the country, go to the Great West, anything rather than remain here" — though he meant places like Michigan, which is not really the West, and not really great. "Your capabilities are sure to be appreciated and your energy and industry rewarded," Greeley wrote, primarily to the New Yorkers who had shown neither capabilities, nor energy, nor industry. It is not clear whether anyone took him up on it. Greeley didn't actually think New York sucked, because despite urging the bums to leave, he himself stayed put.

Dabbling in politics

Greeley's life took another fateful turn when he met Thurlow Weed. While on Weed, Greeley became editor of the Jeffersonian, the house organ of the Whig party, and even spent a month in Detroit. In 1840, Greeley edited the national Whig newspaper, the Log Cabin, and that was before the gays took it over. His writing was crucial in the election of President William Henry Harrison. His reward would be to return to New York City and start another newspaper no one would ever hear of, the Tribune. That is better than what happened to Harrison; Greeley's guy had died after a month in the White House and John Tyler was now President. The newspaper took in $92 in its first week, which would have covered its expenses, if it had been six times greater.

The Tribune continued to dabble in politics, backing Henry Clay even though he had run against Harrison, then disastrously taking a position against slavery and against admitting Texas to the union. However, Greeley did hire Henry Raymond, an assistant editor who went on to start the New York Times, which people have at least heard of, though they no longer read it. Greeley hired a Washington correspondent, then a foreign correspondent, to take the place of boring local coverage, as Greeley assumed everyone in New York City had "gone West."

Dabbling in Congress

In 1848, Rep. David Jackson was unseated from Congress for election fraud, and Greeley said, "I could do that." The Whigs, including some under the influence of Weed, chose Greeley as the new Congressman. The Sixth District was Irish, and Greeley backed Ireland's independence from Great Britain, although Congress could do nothing about that. That stand made Greeley more popular in the Sixth District than he would ever be in Congress, as he spent his time exposing his colleagues' scandals, absences on roll-call votes, and abuse of travel allowances. His other initiatives involved trying to get the Chaplain fired and to eliminate alcohol on Navy ships. Congress adjourned, Greeley returned to New York City empty-handed, and the Whigs next nominated someone else.

But the Tribune was a solid daily newspaper. Some said it was more persuasive than President Tyler, which Greeley thought was a big deal. He became independent of the Whigs, through what they called "Fourierism, Mesmerism, Maine Liquor laws, Spiritual Rappings, Kossuthism, Socialism, Abolitionism, and forty other isms" — the Gerald Ford of his day.

Greeley opposed the bill to let each state decide for itself whether to support slavery, preferring to send armed men into slave states to give the locals a piece of Greeley's mind. The Kansas-Nebraska Act put that question to rest, and put the Whig Party to rest too. The Republican Party took shape as a new anti-slavery party, and Greeley was closely involved and felt it should have nominated him for something, as he had plenty of ideas and his only lack was actual accomplishments.

Going West

In 1859, Greeley took a bit of his own advice, and boarded the Transcontinental Railroad to see what he had been talking about for all those years. He was profoundly unimpressed with the locals, with "small mining towns" like Denver, and with the American Indians — though when he got to Utah, he was impressed with Brigham Young, which got to the Final Four that year. He reached California and concluded that the Pacific Ocean was "no big deal either."

1860 campaign

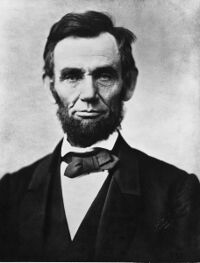

The Republican Party was about to nominate Sen. William Seward, who was not yet known for his famous Folly, but did buy a lot of advertising in the Times and none in the Tribune. Greeley attended the convention, as a substitute representing Oregon (which he had come close to on his tour of the West), and had the last laugh by helping Abraham Lincoln edge out Seward for the nomination.

Greeley assured the nation that Lincoln would never disrupt slavery where it currently existed. Also that Seward would never become Secretary of State. In 1861, Greeley wrote editorials that the nation should let the "Cotton States" leave in peace. However, when the South attacked Fort Sumter, Greeley's editorials promoted war, even at the cost of losing mail subscriptions down South. "Go West, young man" turned into "On to Richmond!"

Following a defeat at Manassas and the brief nervous breakdown that resulted, Greeley turned into a relative pussycat for most of the rest of the year. In 1862, however, Greeley resumed pestering Lincoln for anti-slavery legislation, even after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all the slaves, except those held in the slave states. Greeley supported Lincoln for re-election in 1864, after a bit of respectful flirting with others. However, when John Wilkes Booth cast his vote, Greeley argued for the jailing of Jefferson Davis, though he also helped bail him out, which wasn't great for subscriptions either.

Presidential campaign

Greeley had compiled not just a record of bad predictions and legislative low achievement, but election defeats in 1866, 1867, 1869, and 1870, the selection of less significant offices never leading to more significant results. In 1870, U.S. Grant tapped Greeley as Ambassador to the D.R., but Greeley's response was F.U.

The obvious next step was to run for President in 1872, if a suitable political party were found. The Liberal Republicans obligingly nominated Greeley on only the sixth try. The Democratic Party followed suit, and even promised equal rights for African Americans, the epitome of a promise on which the promiser hopes never to have to make good. Scandal began to surround Grant, while surrounding Greeley was — surprise! — newspaper mudslinging and political cartoons. Greeley's wife cast her own vote by falling ill and dying a week before the election, making Greeley either stop campaigning or look like a cad. Grant won re-election and the nation asked whether Greeley should even be dumped as editor of the Tribune.

This was too much for the old guy, and he died, even before the 66 supportive Southerners were able to cast Electoral Votes for him. They all found someone better to vote for, judging by the presence of a pulse. Greeley had asked for a simple funeral, but his family put on a big bash, a final Greeley prediction that failed to pan out. Ditto the prediction that no one would have a kind word to say about him; there are a couple passages that could be read that way, up in Section 1.

Conclusion

It becomes clear that Greeley's career, while having no tangible results in terms of winning elections and passing laws, far surpassed those first 20 minutes of life gasping for breath. Even those who do not say that that episode was the cause of everything that would go on to occur, believe that Greeley had Asperger's Syndrome, and going without air might have been the cause of that. Many Aspies long to have a celebrity as "one of their own," and Greeley certainly is not going to talk them out of it. Similarly, millions of dyslexic people want a newspaper publisher to look up to, given that they are not going to look down at his newspaper.

See also

| Featured version: 15 May 2015 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |