Advertising

Advertising is the process of presenting a person with commercial messages he does not want to receive.

Advertising is fundamental to capitalism, because the Free Enterprise System produces a cornucopia of products, which the existence of advertising suggests that no one wants to buy based on what he knows about the product. The function of advertising is to provide information he does not know — that is, false information — to induce him to buy products he does not want.

History

Advertising was invented in America. Advertising shows us that Americans were uniquely in need of commercial products. Alone in the world, United States residents —

- Wore wrinkly clothing, with stains that just wouldn't come out, and other intractable problems such as Ring Around the Collar.[1]

- Suffered from debilitating though rococo diseases, including dandruff, the Five O'Clock Shadow, and the Heartbreak of Psoriasis.

- Lived in primitive housing with serious risks, such as indelible Bathtub Rings.

- Were notoriously inept at sex, requiring a variety of patent medicines just to maintain an erection.

These problems threatened lives, the propagation of the species, and thus the survival of the nation. Moreover, consumers often were unaware that they suffered from these problems until the advent of advertising.

Even after rectifying the serious threats to their lives and health, Americans discovered they had utterly no notion of their own identity. Thus, a follow-on function of advertising was to tell the consumer what buying a given car or drinking a given beer said about him. Now, one could plan to become a Macho He-Man or a beauty queen, simply by buying the right products. The consumer can be whoever he wants, at least until the money runs out.[2]

Early forms of advertising

Advertising was initially performed by traveling shows. Professionals called snake oil salesmen would tout their product from the door of a horse-drawn buggy, selling sample bottles to all who turned out to listen. Snake oil had marvelous remedial properties. It would remedy the advertiser of his poverty, while remedying the townspeople of their spare change.

| “ | Ya got trouble, Right here in River City! With a capital "T" And that rhymes with "S" And that stands for—Snake oil! | ” |

—The snake-oil salesman — or, as he became known, The Music Man | ||

Life came to imitate art in 1858, when Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas barnstormed the state of Illinois in their famous debates. They each stood on a soapbox to sell their product — like the salesmen of old — as though it were snake oil.

Snake oil itself is no longer sold due to animal rights activists insisting on better treatment for snakes. The snake oil salesmen themselves have moved to different venues, such as Congress. Much as they can now conduct a filibuster without in fact engaging in all-night recitation of the telephone book, they are usually on their soap boxes, without having to use soap boxes.

The broadcast era

The invention of broadcasting meant that the sales pitch did not have to be taken "into the field" by horse and buggy but could be piped right into the living room, moving radio waves instead of people, as it were. Happily, this societal shift did not reduce the amount of horse manure.

There was a problem with the new paradigm. Small town residents might turn out to listen to the local "Music Man" without realizing that his advertising was a message they didn't want to receive. Betty might be present at the gathering, with her magnificent pair of bezongas, and if the presentation dragged, there would be recourse to spitwads. By comparison, a family gathered around its Boob Tube or Tube Set would be acutely aware of the transition between programming they wanted to receive and advertising they didn't.

Ingenious devices sprang up to convince the audience, in addition to the falsehoods in the advertising, of the falsehood that it isn't advertising in the first place. Through the magic of "product placement," an advertisement becomes part of the program itself. When Rush Limbaugh transitioned from a six-minute heartfelt speech about the width of Hillary Clinton's ankles to a two-minute heartfelt speech about a great new way to preserve the canned goods in the backyard Bomb Shelter, it was product placement at work.

At the cinema, advertising has crept from Previews of Coming Attractions into the feature film itself, again through product placement. Thus we have Thunderbirds, set in an England where everyone including policemen and royalty drive Fords and astronauts drive them into space; and How the West Was Won, showing pioneering stagecoach drivers with bottles of Coca-Cola on the dashboard.

Print advertising

Advertising eagerly flooded into newspapers and magazines, but confronted the same problem, that the reader knew that the page contained both "editorial content" that he wanted to read, and advertising he did not want to read. The advertising industry briefly latched onto the vain solution of full-page advertising, so as to deny the reader the choice between the two, but the reader was only slowed down for a moment, then resumed flipping entire pages at a furious rate.

The more permanent solution involved the use of scantily clad women to pitch the product. Bikini babes now sell everything from automobiles to tour packages. The success of this technique gave birth to the pornography industry, where everything is essentially advertising and "editorial content" is something to be shunned. No one wants a porn flick with a plot. Print pornography pushed the limits with more-than-full-page advertising, that is, the "fold-out," which by all accounts captured the reader's attention.

An exception to the dominance of scantily clad women is the insurance industry, whose products are inexplicably sold by lizards and ducks.

The Internet era

The advent of Internet browsing presented new challenges to advertising, as it gives the end-user unprecedented ability to select desired content and reject not-so-desired content.

Fortunately, technology is racing to the rescue. Innovations such as the new "latest" Firefox version released last night, which your favorite Web services will tell you tomorrow is the only one they support, also Microsoft Windows 11, IPv6, and the proposed Internet2 will usher in a new era in which the web surfer will be unable to view anything of value without first proving he has sat through two TV commercials. Much like HDTV, however, the advertising industry will need regulations to be issued making the current gear unusable.

Sometimes, amateurs take up the profession of dropping advertising messages where they are not-so-desired; for example, dropping them onto wikis in foreign countries. More information on this is available at How Considerable The Duty Of Enjoyment By Delhi Companion On Your Lifetime (or rather, was available).

Economics

The economics of advertising have evolved along with its formats. Above all, advertising is not self-taught nor self-employed. The reader might avail himself of WriteYourOwnWill.com but must never Devise Your Own Ads.

Agencies

Rather, advertisements are executed by an advertising agency. An advertising agency is exactly like a government agency: It does things in your name, as the agency is your "agent"; they are merely things you would never have chosen to do for yourself.

Agencies are full of "creative talent." Creative talent is expert at sensing twists and turns in popular fashion and writing ads that exactly track them; that is, at never being creative at all. Instead, an ad writer must precisely tailor the advertising to the audience. A successful ad writer can produce the perfect advertising for rat poison for a city in which consumers have come to view rats as cute, furry little creatures that are merely chewing holes in walls that would otherwise have to be demolished. The usual strategy for advertising is to make the audience hate what it currently loves, enough to sell it a commercial "remedy." Conversely, advertising that makes the audience love what it currently hates is the field of political advertising.

There is university training for many careers, as even athletes can take courses purporting to teach them how to "manage" a sports franchise. However, there is no university course in writing advertisements. Like being the chief executive of a billion-dollar corporation, it is learned on-the-fly by trial and error, and at the expense of the careers of dozens of other people. However, joining a fraternity is an excellent first step.

The proper orientation of an ad agency is crucial. It measures public opinion and produces advertising exactly tailored to fit that opinion — and pervert it toward the purchase of a product the public would otherwise never buy. Nevertheless, the agency does not work for "the public," but for the producer of the product being marketed. This is the "client." The ad agency actually holds the public in thinly veiled contempt. This not only suggests the recurring analogies to politics but explains why unsuccessful pitch-men turn to careers in politics, while losing politicians begin writing advertising.

The advertising budget

In a typical television advertising campaign, the agency must write the scripts for a thirty-second slot, audition and sign actors to portray modern consumers whose lives will be revolutionized by the product, and manage the filming of the slot.

It is easy to understand advertising by grasping one simple fact: The agency does all those things for free. Then, the agency makes an "ad buy." It arranges with a broadcaster or a network to air the thirty-second slot, considering which stations the desired audience is watching at which times of day. It pays the broadcaster for that time, and sends the client a bill that is cleverly padded to recover the agency's own costs.

Two facts flow from this arrangement:

- A brilliant advertisement that is aired exactly once causes the agency to lose a ton of money.

- A mediocre advertisement, aired every two innings during each of the 162 games of a team in Major League Baseball, is a gold mine for the agency.

These two facts explain why the target audience is sick to death of practically every advertisement it sees.

Like tax increases, repetition of the same advertising eventually arrives at the point of diminishing returns. Each additional airing results in less penetration of the guileless consumer. Returns to the advertising agency, however, never diminish.

There is a single exception to this horrible paradigm: the Super Bowl. As 30 seconds of air time costs upward of $2 million, the agency can recoup its costs by padding the bill for a single showing. Fans of American football gather around the water-cooler at work the next morning not to discuss the 24-3 final score, the cheap hits the winners made after the game was already virtually decided, the flagrant pass interference violations that were not called, nor the time spent waiting for the referees to go "under the hood" and conduct Further Review, but about the advertising during the program. Indeed, viewers in the 30 teams that washed out of the playoffs before the Super Bowl watch the broadcast religiously, because everyone else at work will be discussing the advertising. One can't claim, "I switched the channel because they were rerunning an episode of Game of Thrones I hadn't seen."

Account under review

Recall that the purpose of advertising is to deliver messages that the audience does not want. Because of the above funding mechanism, the agency also delivers the client bills that it does not want. For example, given a "successful" ad campaign that uses deliberately bad singing and cheap production to convince the audience that donating a car to the client will somehow benefit starving orphans, the deliberately bad singing goes on forever, as the agency's funding remains a percentage of all the time it books.

The client has one option; not demanding that the agency switch to fewer or less expensive ad bookings (because only the agency is an expert at advertising), but putting the account under review. This entails numerous high-level meetings in which the non-experts dither toward a non-decision, which mostly reflects interpersonal antagonism and the quality of the food catering. The agency may send a representative to these review meetings. She has no information about either the conduct or the results of the ad campaign, but knows how to act as deferential and obsequious as a recently whipped slave. Meanwhile, the client avoids suggesting that her agency is awful, but instead issues a press release about "moving in a different direction," much like a ball club strains to explain dumping its World Series manager after starting oh-and-20 the next year.

Moving in a different direction means that the deliberately bad singing will continue, but the continual monthly bills will be payable to a different agency. Depending on the contract, the new agency might have to commission different bad singing. If the client has gone five years before putting the account under review, the new agency may conclude that there is enough loot on the line to perform "creative" effort of its own. Perhaps Animatronic puppies.

Some clients that have "moved in a different direction" schedule a remarkable ritual. The client invites multiple advertising agencies to come to it with proposed new campaigns, to compete for the account. Each agency puts forth its most nearly creative work, for no money at all. Disasters are occasionally nipped in the bud (pictured). However, agencies will only work for free once they are convinced that the client is even stupider and will pay monthly bills indefinitely to the winner during any subsequent lull in creativity.

Measuring results

Any good advertising campaign involves tests to see if it is effective. There are two components of this test:

- A straightforward analysis of whether the client's sales increased during the advertising campaign.

- An inscrutable analysis of whether the results were a consequence of the campaign.

This involves asserting that a sales increase would not have happened in the absence of the campaign, or conversely, that the boycott that went viral was not a result of using your air time to nag the audience about its toxic masculinity. That is, the test depends on post hoc ergo propter hoc, which is Latin for, "We can give these assurances to a Six-Sigma level of certainty, for a mere doubling of the fee."

Ad agencies always measure the results of their ad campaigns. Polling determines what percentage of the public remembers those Animatronic puppies, or can sing the client's current jingle. Ad agencies never measure what percentage of the public can recall who the client is or what its product is.

For precise measurement, the client must go beyond the vagaries of the ad agency. It must sign up for the gigantic vagaries of a marketing consultancy. This too is an agency, but it makes no media buys. It produces a report, of hundreds of pages, for which it bills the client on delivery. While this is a more honest business, it is not because anyone will be able to read its report. Happily, however, the report has a one-page Management Summary.

Techniques

The advertising industry recurs to several easily understood paradigms. A paradigm is a strategy to message the audience into buying a shoddy product.

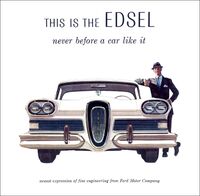

Simple mendacity

The most common way for an ad agency to induce the consumer to buy a product is to simply lie about it. Now, offering for sale one thing, and delivering a much different thing, is bait-and-switch, and it is very very bad. In advertising for cars, the ad agency describes the product, and delivers exactly the product described. The description is simply not true.

For example, the selling price includes mendacity, because it excludes:

- The destination charge, as the buyer certainly wants to drive the car off the lot and not take a bus to the coast to pick the car up at the pier.

- Dealer prep, the cost of the dealer taking a completely different car out of the back lot and making it nearly as attractive as the one the buyer test-drove. This too is a necessary charge. Without prep, the vehicle would remain covered with Saran Wrap, and would lack that new-car smell that the technician sprays into it.

- Registration. Everyone agrees that cars must be registered, and no one wants to get a citation the instant he drives off the car lot. Modern car dealers can process all the paperwork on-site (for only a hundred dollars more than the filing fee for the same thing at Town Hall).

- Taxes and fees. No one wants anarchy, so this line item covers taxes and fees arising from the sale, such as sales and excise taxes; also taxes and fees having nothing to do with the sale, such as the need to keep the bright lights lit in the showroom.

The above charges are very close to the taxes that Barack Obama told an eager nation that "you'll never see a dime's worth of." And indeed the buyer does not. The monthly car payment is a double sawbuck higher than you expected, but you've never been very good at math.

Advertisers who are not bold enough for full-strength mendacity can still participate, with the help of the pert little asterisk. For example:

- The car has air conditioning.

- The car goes zero-to-sixty in 15 seconds.

- The car gets 40 miles per gallon.

- But not if you have the air conditioning on.

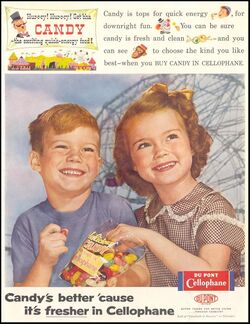

Corrupt the family

Occasionally, there is simply no way to pitch a lousy product. This is when an agency's "creative talent" gets creative:

- What would the Missus like? Social legitimacy? A feeling she is beautiful? Raw power over family politics? Perhaps the product can provide that.

- How about the children? Can they be gotten to pester the Breadwinner until he wilts?

- If everyone down at the Club began wearing kilts, wouldn't you go along?

The ad-man, like the surgeon, understands that there is always more than one way in.

Pound the table

The ad-man has much in common with the lawyer, who understands that occasionally neither the facts nor the law favors your argument so what you must pound is the table. Sooner or later, every ad agency must do business with an even more loathsome agency, an insurance agency, and develop an ad campaign to convince the unwilling audience that:

- If you pay now, the insurance agency will pay you back later if a mishap befalls you.

- There is no one in that skyscraper writing rules that will deny you that payment.

- A website can give you better customer service than that clueless backslapper in a suit in the downtown office who went to school with your father (Boy, I could tell you stories).

Preposterous on all three counts. The ad-man's snap solution? Bring in the ducks and lizards!

Advertising must often sidestep whether the product is any good, when there are legal or other reasons not to show the actual product in actual use, from beer to toilet paper. Ducks and lizards do not sell beer, but Clydesdale horses might. Usually, the ad agency turns to humor — which gets oddly unfunny when viewed for the 1000th time.

Advertising ethics

Ethics is vital to the advertising business. An example of ethics is the study of how to make a case for misstating the price of a car for sale. This boils down to three principles:

- Everyone else in the industry is doing it too.

- Doing it enables us to present you with offers you may appreciate.

- We have to do this; otherwise, we could not sell the car.

In other words, advertising ethics is identical to date-rape ethics.

Recent developments

Disclaimers

Modern government has responded to the flagrant dishonesty of modern advertising by dictating that advertisements must come clean and tell the truth by the end. This has led to the institution of fine print. Fine print is at its finest in advertisements for medicine, though it takes quite a while to list all the scary adverse symptoms you might experience. A typical advertisement may end by stating, "Visit our website for details." This indicates that the entire advertisement was untrue, but the consumer can find out exactly what the lies were, on-line (be sure to click for the "fine print").

Despite a promising Supreme Court ruling in 2018 that it can't be free speech if we tell you what the words must be, the government continues to mandate disclaimers. Legislators typically return to their districts and brag about doing this instead of voting for tax increases. (Disclaimer: They did that too.)

Legislators believe there is no limit to the number of disclaimers they can mandate. Of course, they also believe there is no limit to tax increases. However, of course there is: The available width and height of the advertisement. The ad agency adapts effortlessly by continuing to reduce the size of the print. Modern materials technology means it will not be long before every magazine can include a rip-out magnifying glass.

Broadcast ads also easily adapt to an increasing number of mandated disclosures, given that every phone can now compress speech without having to phone Alvin and the Chipmunks. The law merely says the advertiser has to utter these words, not that the audience has to be able to make them out.

The reason these adaptations are so easy is that, again, advertising consists of messages the consumer does not want, and disclaimers are simply more of the same.

Targeted advertising

Historically, advertising has always been a broadcast in the most general sense, widely diffusing one's message like an oak tree dropping acorns everywhere and hoping a few don't hit pavement. Advertisers are open to new technology to guide their messages toward pay dirt.

Legacy media help somewhat. For example, a new evangelical church is able to advertise where sinners congregate, such as on the pages of Hustler. Aerosol deodorants advertise so as to select an apt audience, such as on New York Yankees telecasts.

Social media, collecting gigabytes of sensitive personal information about their users, can let agencies precisely target their advertising. For example, Russian 'bots trying to influence a U.S. Presidential election can elect to send their message only to Facebook users who state a preference for Hillary Clinton, and offer them damaging information about her, especially a couple weeks after the election. The advertising can be geographically targeted, as well, hitting mostly states that she won anyway.

Such targeting of advertisements lowers their cost — which the agency never cared about in the first place, as the bill, after padding by the agency, is sent straight to the client.

Personal advertising

Those late adopters who worried that the cellphone was merely an attempt to attach a vending machine to their bodies got it all wrong. In point of fact, it is a remote-controlled vending machine, a crucial way of getting the signature unwanted messages of the advertising industry directly to you, especially given the innovation of paying even for calls you didn't place. Ideally, you are so annoyed at paying for the call that you will not be annoyed at all at the pointless message.

The agency lowers the cost of this advertising, to everyone but the target, in several ways:

- It puts the pitch-man in a place like Pakistan, where wages are lower, and the message can be delivered in a charming if inscrutable foreign accent.

- It uses a robot to dial the phone, avoiding putting a pitch-man on the line at all until it seems a live person has picked up.

Sometimes no pitch-men are available when the call goes through, but a voice will come on the line within 15 seconds or so. The person answering need only shout, "Hello? Hello?" a few times. The U.S. government, in consultation with the advertising industry, puts strict limits on the percentage of time you answer a call and there is no one on the line at all; while a separate agency of government has prohibited robo-calling entirely, except for politicians, charities, and those who put their sales pitch in the form of an "opinion poll."

With this medium, though the agency can mislead as usual about the product being advertised, it is not possible to conceal the fact that it is advertising. ("Hi! This is Sruthi! How you are doing? You are having a good day?") However, it is now possible to get one initial lie in, by displaying a phone number other than Pakistan. An attractive way to make the target answer the call is to claim to be in his own city, or in an attractive tourist destination, such as Chicago or Grand Rapids. Many people answer calls from these locations simply on the off-chance that it is a voluptuous single woman calling to fly you in for a steamy one-night stand.

IHeartRadio

In the 2010s, talk radio continued to decline, while advertising continued to prosper. Given the shifting economics, one business — with the single message that you would be the coolest person in your neighborhood if you simply let us put our code into your phone (and do please enable location-tracking and the selfie camera!) — searched for new ways to spread that message.

Rather than contact a radio network to buy time, the business pursued a quantity discount, buying a radio network so as to own all the time. Now, despite the annoyance of having to pay staff, apply for broadcast license renewals, and procure content, the business can air its ad as often as it likes. This gave us IHeartRadio. In the future, the company will actually sell advertising time (which means it will have two separate motives to air advertisements more often than anyone can stand it). However, most IHeartRadio stations have not gotten to this point. During commercial breaks, they do nothing other than play medleys of hits from 1972, assuring listeners who happen to be stuck in that year that they can hear it all the time by merely downloading the app. Otherwise, they will hear the same ad all the time.

Paid programming

Those without the resources to purchase an entire radio network, nor anything better going on in their lives, can still dabble, by purchasing an hour a week of weekend airtime. This lets you buy your way into a radio station's stable of audio stars. Instead of attracting listeners to hear the station's advertisements (because you don't attract listeners, apart from Mom), you can be one of the station's advertisements, sub-letting one-minute breaks to anyone you can convince to buy them, in vain hopes that the total will cover your own costs.

Between those sparse advertisements, you can broadcast whatever content you want, and call the show anything you like. You can dispense financial information that is only indirectly self-serving, or explain how the Issues of the Day all work back to the Koch Brothers or the Trilateral Commission. An exception is that, lately, The Lutheran Hour is done after a mere 30 minutes.

See also

| Featured version: 6 June 2019 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |