Citizens Band

“Ten-four, Little Buddy...over?”

Citizens Band or CB is a radio service in the United States, and anywhere else people like to pretend they are Americans. Citizens Band is like a wiki or IRC where everyone is an IP.

Citizens Band arose in the 1940s as a rebellion against commercial radio, on which information was getting too reliable. It enjoyed popularity in the 1970s and early 1980s, based entirely on the lack of decent alternatives, and briefly exploded into a worldwide fad based on a pretty awful movie. It retains its popularity in the Southern United States, alongside moonshine and adultery, and can still be enjoyed today, although drunken monologues emanating from Tennessee mountaintops over linear amplifiers drown out local and relevant conversations.

History

The United States established Citizens Band as a national institution just before turning its attention to the somewhat more destructive World War 2. There were originally 23 channels, assigned irregular frequencies. The earliest Citizens Band users (referred to as Good Buddies) received a Citizens Band "rig" for Christmas and immediately rushed to Radio Shack with any presents that had come in the form of cash to buy crystals tuned to the two or three channels they had decided to take a chance on.

Operation required a license, and this required a cash payment and a long wait for a letter in the mail with a certificate suitable for framing behind the desk that would become one's Base Station. But unlike ham radio, the licensee did not have to learn Morse Code, memorize a long list of frequencies and be able to recite the proper operating modes on each of them, and demonstrate the technical ability to disassemble a radio and put it back together blindfolded. Most of these skills required coursework at meetings of other hams, where everyone dressed alike, down to the pocket protector and nerd strap.

Although the regulations did not require technical skill, the radios did. After buying a radio, you had to buy an antenna, and then pay a technician with a signal-wave-ratio meter to "match" the antenna to the radio, or else you would get too much signal, too much wave, or too much acrid smoke billowing out of the radio.

In place of the technical training was a pamphlet known as Part 93. It only required that the Good Buddy keep his transmissions brief to let others interrupt, and not discuss anything more useful or political than the quality of each other's signal. However, as the frequencies were policed as poorly as anything else the U.S. Government polices, having to learn these rules did not mean one had to obey them. This meant that Citizens Band achieved popularity among truckers, geeks, and lonely single men.

International adoption

The desire to act like Americans led most countries outside the U.S. to offer a radio service likewise tailored to the untrained and undisciplined. These countries fell into two groups:

- Countries that were not serious enough about it to do anything but copy the U.S. rules and frequencies, and

- Countries where "national pride" required them to devise different frequencies, kicking off a long wait to see if anyone would make radios for them.

Technical advances

The first quantum leap forward was the frequency synthesizer, which meant that a rig could support all 23 channels. Given the inscrutable gaps between frequencies, this meant that each rig needed a gigantic selector knob attached to an even more gigantic gang of switches. It also meant that that generation's version of the hacker busied himself installing extra switches to short out the knob and gain access to the channels between the legal channels, such as the smutty secret that was 22-A. This is one of history's rare efforts by which an individual contrives to be heard by fewer people.

Although a 23-channel radio was futuristic, recall that this all happened in The Past, where $59 was a lot of money. It was unthinkable to discard your CB radio with crystals for Channel 4 and Channel 8, even though you had heard that truckers were saying really gritty things up on Channel 19, and actual fires and robberies were being called in on Channel 9. You were not going to just put the old radio on eBay. So when the gang went to a new channel, most Good Buddies saved up lunch money, bought additional crystals, and opened up the radio and swapped them in.

Sudden popularity

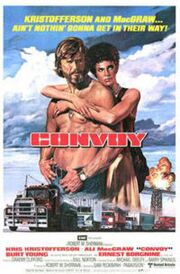

Citizens Band gained instant unwarranted publicity thanks to a movie, even before roller derby did. In Convoy, a truck driver named Rubber Duck uses his radio to organize a massive convoy of trucks as a protest of something-or-other. The movie was a huge commercial success that really isn't worth seeing. But its characters gave the audience an instant feeling of superiority, and the desire to feel it weekly led to the television series Dukes of Hazzard.

These shows brought about an immediate explosion in the popularity of Citizens Band, which did not change the fact that it still required a license. If it was Mother who gave you your rig for Christmas, she would surely insist that you not use it until your license arrived. And, surprise of surprises, the FCC was overwhelmed.

Their personnel were planning for an imminent crisis. They were soon going to issue license KZZ 9999 and would have to do the unthinkable: Go to eight-character licenses, starting with KAAA 0000. This only made matters worse, as even people with no desire to wish everyone a Big Ten Four put in for licenses, hoping for the shorter license signifying an Early Adopter who could rightly boss around the young punks who came afterward.

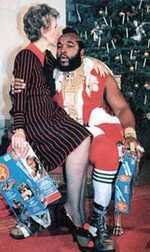

At the same time, America was getting an equally useless Christmas present — Ronald Reagan — whose wife Nancy suggested that radio operators could, "until their licenses arrived," cobble a license number out of their initials and ZIP code. Now you were KJRJ 90125, as a lot of other people were too, and no one cared that licenses were now nine characters long. To add to the confusion, a rig located in 90125 still had insufficient power to reach anywhere outside 90125. This meant that all the new licenses were three characters long. But the suggestion came from the Office of First Lady, and was an invaluable excuse, as there was no time limit on how long one could claim the "check is in the mail."

In the wink of an eye, the FCC announced that it would not issue licenses at all, even if you mailed it money. Your coveted seven-character license was now useless and the radio band was a free-for-all, a change that was less than palpable. These same three phases — nit-picky regulations, elastic exceptions, and collapse and surrender — would soon be applied on the nation's southern border.

More technical advances

The myriad employees no longer engaged in stamping out Citizens Band licenses were diverted into more vital work: catering to the radio manufacturers lobbying the agency. These manufacturers had sold a rig to every single American, and their survival now required finding a way to force everyone to junk all their existing rigs and buy new gear.

The solution was to expand the service to 40 channels, and in the wink of an eye, decree that all new radios would have to support all 40. There has never been anything near 23 channels of good conversation, nor anything important discussed above Channel 23 (nor below it), and most of the new channels were reserved for needless experiments such as using sidebands to have two needless conversations on the same channel. Nevertheless, everyone ran out and bought a new rig (ka-ching!), ensuring that the same regulatory strategy would later be used to give a big, green-backed kiss to makers of HDTV and routers.

The final technical advance was to put all the tuning electronics on a single chip. This instantly dashed the hope of rewiring your rig to gain access to naughty conversations on illegal frequencies, or to solder in a linear and overcome the built-in two-mile transmission limit. The popularity of Citizens Band was gone and it now survives as a niche industry among radio buffs who lack the attention span to get a ham license, and in most cases even to get a ham sandwich.

Operation

Handles

In the United States, a Good Buddy no longer needs a license, but use of a handle is obligatory. In the absence of a license number, Part 93 requires handles to be broadcast at frequent intervals — so that the person talking is identified, right? Like bakeries and pet shops once the swells gentrify your city, every handle has to include some sort of pun. Handles are like usernames in chatrooms on the Internet. They usually reflect how the owner wishes to appear rather than what he is really like.

Slang

Good Buddies invented their own jargon, a sort of audible Leet. Like carnival hands, CB users wished to keep their reports on locations of speed traps secret from the police — though the police knew the jargon better than most CB users did, and had a CB in the cruiser themselves, so they could tell when the speeders were clued in and the cops ought to set up somewhere else. The police themselves are known as smokies, whether they are state police wearing Smokey the Bear hats or local police with the eight-sided ones.

Any Good Buddy wishing to transmit must first make a transmission of "Breaker one nine," or whatever the channel number is, and wait for formal permission from another user to broadcast. The rationale is that, if there is no other user to grant permission, then he would be broadcasting to nobody — and if he wanted that, he would edit Uncyclopedia instead. In practice, the new speaker never receives a reply inviting him to broadcast, and bulls forward without one. The reason for this formality is that Citizens Band radio is designed so that, if two users broadcast simultaneously, neither is heard. This is also the reason that nobody ever steps forward to grant the break.

When the Good Buddy has finished speaking, he must signify by saying "Over," so that the other users don't have to sense silence to know that the channel is silent — which they are supposed to do anyway, to give a chance to another Breaker. Modern users avail themselves of the Roger Beep, where their rig indicates they have released the Push To Talk. This means that, in the rare case where a user has a pleasant voice, a horn sounds at the end to jolt you back to revulsion.

During the transmission, you must use ten-codes, which help users pretend they are police — or rather, smokies. For example, if you wish to say "Yes," you must instead say "Ten-four," to avoid confusion. Over time, "ten-four" is stylized to "ten-forty" and thence to "forty-roger," which technically is not a ten-code but a forty-code. There are no other forty-codes. Similarly, if a Citizens Band user asks you, "What's your ten-twenty?" simply read your wristwatch to him. Other ten-codes advise listeners that you are monitoring the channel, as though anyone cares; or that you are going to stop monitoring the channel, which won't make or break their day either. There is "no" ten-code for "No."

Oddly, there never was a ten-code to refer to the professional FCC personnel who monitored each Citizens Band channel to ensure its orderly use.

Decline

There are exactly two CB radio brands left, Cobra and Uniden, and if they are anything like Radio Corporation of "America," they both represent a one-man office importing gear made in Red China where the wise citizen does not ask for a Break at all. The packages are so similar that the innards must be identical.

In 2019, Uniden started an advertising campaign celebrating its 55th birthday and calling on Americans to take up the hobby again. As though our phones weren't working, as though they weren't smaller than a piece of flatbread, as though they didn't have better power management and more attractive displays than radios ever have had, and as though they didn't include a music player, a movie studio, and the correct time-of-day, so you don't have to ask for a Breaker Breaker in the first place.

Rather than ask why Citizens Band has become so unpopular, we should ask why we ever liked it. The answers are as follows:

- It did something we could never do before, so like a randy teenager, we wanted to do it all night, every night.

- We had no idea things could be better — that information could be accurate, that you could get the exact information you wanted, and that it could come from someone other than a grifter waiting around the bend to rob you.

Modern Citizens Band hangs on, on every American's eternal hope of locating a teenage girl at the next truck stop in urgent need of a ride and willing to pay in-kind. Many recent state laws prohibiting telephoning while driving make exceptions for Citizens Band use — not to show that legislators were never serious about anything but placating the busload of schoolmarms in the legislative hearing room, but because Good Buddies don't seem like jerks, as do Valley Girls yapping on their phones as they veer into your lane. This is because we have forgotten.

But Citizens Band radio is like comparing a fat chick to a moped. They are fun to ride, but you don't want anyone to see you doing it.

| |||||||||||||

| Featured version: 10 March 2020 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |