Moby-Dick

- "The Whale" redirects here. There may be a whale, but this is The Whale. The definite article, you might say. Clear?

|

Melville's Encyclopædia | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Title page of the first edition. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pertinent Information | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Melville's Encyclopædia of Whales and Whaling (Latin for "Melville's Encyclopaedia of Whales and Whaling") is an English-language encyclopaedia written by the American Herman Melville. First published in 1851 in London, the reference work is viewed as having the definitive word on all things related to whales and the whaling industry.

Moby-Dick, the name of a whale sometimes prominent in the contents of Melville's Encyclopædia, has traditionally been an alternate title.

History

Several events in or during Melville's life influenced him to write a work on natural history, and in particular on whales and whaling. For instance, after a career largely spent on school-teaching, he spent 18 months on a voyage that he later said began his life. This was on the whaling ship Acushnet, which he called "my Yale College and my Harvard", presumably because they made him just as sick as did a sea voyage.

Indeed, the most significant event in that voyage turned out to be his desertion from the ship, which led to adventures with natives of extremely remote islands. Melville later recorded these in his best-seller novels Typee and Omoo, viewed by contemporaries and by most modern literary critics as the high point of his fiction-writing career. Presumably that was what he meant when he said that his life began with that voyage, since whaling seems to consist mostly of looking for squirts of water and creatures that make them—not the most life-changing experience.

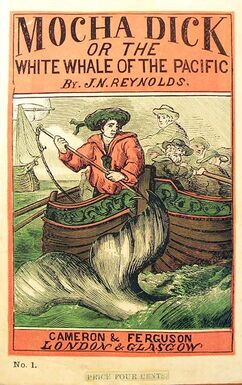

The most bizarre of all inspirations, however, might be the allegedly successful harpooning of an albino sperm whale, Mocha Dick, named so because all of his spermaceti was supposed to have been replaced with caffè latte[1]. Melville, being a tea drinker, thought this obsession with coffee absurd, and decided that it symbolised impeccably the futile nature of man's pursuit of the mysterious.

These factors, combined with Melville's desire to branch out into non-fiction following Nathaniel Hawthorne's extremely, extremely painfully detailed biography of 17th-century Bostonian Hester Prynne, ultimately led to the writing of Melville's Encyclopædia.

Contents and features

Articles

The encyclopaedia consists of 42 articles, in the form of what may be considered essays by Melville attempting to tackle a certain aspect of whales, the industry out to exploit them, or the history of either. Select editions are accompanied by wood engravings for readers who, rather than admire the masterfully crafted prose of Melville with its stylised language, extensive symbolism, and stark raving madness, would prefer to look at the pretty pictures.

Subject matters treated include:

- Nantucket

- Hierarchy of the whaling industry

- Whales in popular culture

- Harpoons and their crotches

- "Finders, keepers" in whaling

- Processing of whale oil

- Whale penises

While the 42 articles are obviously erudite, articulate, and comprehensive, they are arranged in a highly unconventional manner for a work of natural history knowledge. The arrangement is certainly not by alphabetical order, category, or even average customer review.

Hidden narrative?

Instead, the articles are inexplicably separated by large sections that seemingly have no relation to descriptions of whales or of the whaling business. When spliced together, these sections appear to form a frame narrative for the entire encyclopaedia, concerning a captain attempting to catch a white whale. While completely irrelevant to the rest of the Encyclopædia, we will nonetheless, in the interest of scholarship, delve further into this inscrutable inclusion.

Encyclopaedic content

As a matter of fact, the frame narrative itself also has titbits of whales and whaling; indeed, some of them may very well have been articles themselves were it not for their anecdotal nature, which is the only distinguishing factor between the articles and the narrative chapters. For instance, Melville has the narrator describe a whaler, Queequeg, who is native to a remote Pacific island:

| “ | When a new-hatched savage running wild about his native woodlands in a grass clout, followed by the nibbling goats, as if he were a green sapling; even then, in Queequeg’s ambitious soul, lurked a strong desire to see something more of Christendom than a specimen whaler or two. His father was a High Chief, a King; his uncle a High Priest; and on the maternal side he boasted aunts who were the wives of unconquerable warriors. There was excellent blood in his veins—royal stuff; though sadly vitiated, I fear, by the cannibal propensity he nourished in his untutored youth. | ” |

—"Ishmael", segment leading up to "Nantucket" | ||

Using the technique of immersive learning, Melville thus gives the reader a picture of savage Pacific islander life, hierarchy, and savageness that is completely factual and not at all racially insensitive in stereotypically portraying the noble savage. However, at least half of the narrative does not even contain this subtle form of education, and instead consists of idle philosophising, contemplation and character study. The sensible reader will realise that since the narrative is fictional, such drawn-out segments have no meaning to the overall work of the Encyclopædia and thus may be safely ignored. However, this article being an esoteric study of the work, we shall regrettably examine the rest of the narrative as well.

Non-encyclopaedic content

The remainder of Melville's Encyclopædia is the simple story of a monomaniac attempting to catch a whale, but laden with symbolic and philosophical tediousness. Set in contemporary (i.e. 1850s) Nantucket and Pacific waters—although the names of the characters mostly seem to establish a setting of the ancient Middle East and the Red Sea—the plot follows a whaling ship named after a doomed Native American tribe, and features its crew:

- "Ishmael" is the narrator of the story, and a former schoolteacher who boards the

AcushnetPequod out of a desire for adventure, and of questionable judgement since he boards a ship named after a doomed Native American tribe. His presence does not drive the story; he is an outright literature geek and is of little use aboard the voyage. In addition, his name signifies exiles, outcasts, and, in general, losers. All this considered, Ishmael's sole reason for existence, it may be safely said, was for Melville to insert himself into the story. - Ahab is the captain of the Pequod, and believes that the White Whale is the focus of evil itself, largely because it tore his leg off. He is also of questionable sanity, since he believes an occupational hazard to be possessed by the Devil. Another incident to substantiate his madness is his question, "is Ahab, Ahab?", since Ahab is, unfortunately but clearly, Ahab.

- Starbuck is the first mate of the Pequod, and was reportedly based on the man who harpooned Mocha Dick and made a fortune operating a coffee chain that was derived from the whale's latte and not named after a doomed Native American tribe. He serves as a foil to Ahab with the viewpoint that the White Whale is simply an innocent albeit unreasonable creature of nature. He is also of questionable sanity, since he still blindly follows a man who believes an occupational hazard to be possessed with evil. Despite being given the opportunity to kill Ahab and turn the ship around, Starbuck simply chickens out just so that Ishmael can wax poetic about life and death and revenge and the image of Ahab and Moby-Dick sinking together into the deep ocean, entangled together by Ahab's harpoon and passion for vengeance—all of which is completely irrelevant to whales and whaling.

- Stubb and Flask are an A-list comedy duo on the level of Abbott and Costello, Fry and Laurie, and Laurel and Hardy, and are on the Pequod for no conceivable reason. Therefore, they are also of questionable sanity.

- The harpooners Queequeg, Tashtego, Daggoo and Fedallah are personifications of various racial stereotypes. This means that Melville is of questionable sanctity.

In these sections, Melville follows extremely dramatic, exaggerated, poetic, and outright mad language:

| “ | Now, three to three, ye stand. Commend the murderous chalices! Bestow them, ye who are now made parties to this indissoluble league . . . . Drink, ye harpooneers! drink and swear, ye men that man the deathful whaleboat's bow—Death to Moby Dick! God hunt us all, if we do not hunt Moby Dick to his death! | ” |

—Captain Ahab, segment between articles "The Mast-Head" and "The Whiteness of the Whale" | ||

The narrative as a whole is admirably written, and raises various salient metaphysical and otherwise philosophical points. However, all of this bears no relevance to the main body of Melville's Encyclopædia and so, outside of the brief examination conducted in the past few sections, may be completely ignored.

Melville's Encyclopædia today

Melville's Encyclopædia has received strong criticism for becoming increasingly outdated. No revisions were ever made to the content after the original 1851 publication, which means that subsequent editions still fail to cover modern, relevant, prominent topics such as the scarce need for whale oil, the worldwide ban on commercial whaling, and very attractive (possibly biased) actresses who oppose international whaling and should definitely be discussed because they are very attractive.

However, keeping Melville's Encyclopædia up to date no longer appears to be one of Melville's top priorities. Since the encyclopaedia's publication, Melville has since moved on to fiction novels and short story collections—a drastic shift from this non-fiction opus—and as late as March 2026, appears to be a little lethargic.

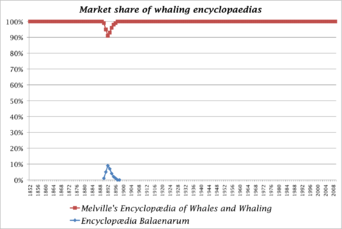

Competition

With the decline of whaling as a viable or legal commercial venture, Melville's Encyclopædia has seen little competition in the way of the whaling encyclopaedia market. Initially, the Encyclopædia Britannica attempted a venture into the market in 1890 with the Encyclopædia Balaenarum (Latin for "Encyclopaedia of Whales"), a 13-volume encyclopaedia with far more thoroughly researched and sensibly arranged articles compared to those in Melville's Encyclopædia; however, its market share never rose above 10%, and the venture finally folded after the management realised how very few captains wanted to bring a 13-volume encyclopaedia on board, let alone read it.

Today, Melville's Encyclopædia remains a dominant force, consistently maintaining 100% market share in the US and UK whaling encyclopaedia markets. Nevertheless, the Encyclopaedia of Wales have admitted that an estimated 14.3% of their customers each year buy the publication believing it to be about whales[2].

Alternative interpretation

In the early 20th century, modernist literary critics began to examine Melville's Encyclopædia as a work of art—not in the sense that Marcel Duchamp makes a urinal a work of art and then laughs at everyone who does treat it like a work of art, but in the sense that works of art composed as works of art are seen as works of art. In fact, most people today view Melville's Encyclopædia not as an expertly researched and thoroughly written reference work on the whaling industry, but rather as one of the Great American Novels. Many—though fortunately not all—schools have switched from using the text as an intermediate textbook in whaling courses, to using it as a novel exemplary of American Romanticism.

Obviously, however, all of this is in grave error; such people have made the mistake of confusing the frame narrative for the main portion of the text. Most literary critics, however, agree that the narrative was an unnecessary attempt to transition between the articles, in an experimental encyclopaedic format that was never seen again. Melville's chief aim in writing the text, after all, was to be educational and definitive, and to record history as he saw it; and that such a goal would even dare to be attempted through fiction would be something only romantics would argue for.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ The spermaceti of a sperm whale is the wax harvested from its head, and therefore is the most valued thing about sperm whales. Since Mocha Dick's head had no spermaceti, and most whalers prefer espresso over latte or cappuccino, the whalers' obsession with this whale was just as inscrutable as the whale's biological processes.

- ↑ This has prompted a statement from the publisher asking the general public to be more educated in the future about homonyms.

| Featured version: 29 December 2010 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |