Tapir

The tapir (pronunciation unknown, possibly as "tay-per" or maybe "ta-peer", but not really important), (Tapirus robitusseus) from the Latin tea, meaning "ferocious rape monster of the dark forest", and pir, meaning "sunshine" or "vulva", also known as the pigopatamus, is a very big and completely useless jungle-dwelling forest creature that is neither a pickle nor a melon but rather something entirely different. The tapir is generally regarded as the world's largest land rodent, and, despite its unusual features, is also both a pig and an antelope as well. With females weighing upwards of 15 tons and males sometimes even more, the animal is rivaled only by the rhinoceros as the world's largest living organism.

Appearance

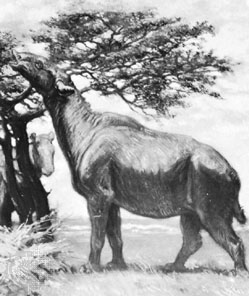

The hideous tapir is certainly something to behold, if you dare to search for it. The tapir is very secretive, but, due to its pungent aroma (reminiscent of onions and poop), is easily located with a bit of effort. It is also helpful that the tapir is also enormously humongous—even more so than a very, very small baby whale. It easily towers over even the tallest of small children, which a very, very small baby whale could never do. Most tapirs are an obscene red color with uncountable millions of small pink splotches, but just as many can be blue or even brown, or rarely even pale mauve, like a school bus.

With legs as thick as redwoods, the tapir makes the ground quake with each thundering step. Its head is small; its snout is blunt and ends in a flexible, weaselly snout, which it uses to scratch its forehead and to bludgeon frightening creatures like baboons. The animal has short, freckled ears and black, beady eyes grossly coated in thick, protective eye mucous. The tapir's skin is dark and leathery, and so thick that even the sharpest of spoons couldn't pierce it. Its tail is thick and powerful enough to break a lions face into a bazillion pieces with one smack. Unlike a duck, the tapir's feet end in sharp hooves, which it uses to crush any of the things it may want to crush and its teeth are so strong it can crack even eggshells in a single bite. Most tapirs have three toes on some feet and four on others, but some may have five or even six on each foot, and some on the nape of the neck as well.

Habitat

The tapir is found in dark, scary forests and warm, sunny meadows throughout most of Australia, and sporadically throughout the rest of the world, with isolated populations thriving in Chicago, Capetown, Istanbul, and Hamburg, among others, with the largest population outside of Queensland found in England. A small sort of tapir was once abundant in India and throughout the Middle East, but it died. There was once a rather ugly sort of tapir found in the Netherlands, but it also died, much like the tapir that was once found in Tasmania but which has since died also.

Tapirs in the wild are never found near large rocks, which frighten them unimaginably. Conversely, it is rare for them to live far from small rocks, which do not frighten the tapir but sexually excite it. Populations are quite variable in areas where medium sized rocks can be found, depending on the relationship in size between these rocks and those surrounding them. Sometimes a lone tapir may be found far from any noticeable rocks at all, but this is very unusual, and usually indicates either advanced yuckiness or terminal illness in said individual.

Diet

Tapirs eat moss and only moss. Every minute of every day is spent foraging for moss; a single animal may eat over 500 pounds of moss in one day. Sometimes tapirs like to search for moss on the ground; other times, they may find the moss on a tree or a rock. Sometimes, the moss might even be found nearby sticks or fallen leaves. Occasionally the tapirs eat all of the moss and millions of them starve to death while the moss grows back. But once it is back, the tapirs are right there to eat it. Never will you observe anything so profound as the tapir's relationship with the moss. It is truly something to marvel at.

Behavior

Tapirs are solitary animals for most of the year, spending most of their time foraging for moss (see above). At times, they may also urinate, but usually they will urinate while simultaneously foraging for moss. The animal simply does not have the time to do both individually. Sometimes, a tapir will tire of foraging for moss, and will decide to search for moss instead. This affords the animal countless hours of enjoyment until searching, too, becomes tedious, and the tapir decides to hunt for the moss, which again provides more enrichment to the tapir. Very little can distract a tapir from its various moss-finding behaviors, except for when it has time to hide under the bed or lick some dirt. Being very large like a walrus, they have few predators, and thus it is rare that they find themselves bothered by anything, except sometimes bright sunlight, which may burn their delicate skin. Still, sunburn aside, nothing on this Earth, with the obvious exception of large rocks, can frighten a tapir, unless, God forbid, it rains.

Tapirs are terrified of rain. Even a single raindrop sends the herd into blind panic. The smarter tapirs, of which there are none, flee for cover, but many are so overwhelmed that they collapse to the ground and die, so conflicted that their little brains simply explode from uncertainty. Sometimes a tapir becomes so afraid in a rainstorm that it forgets even its most basic survival instincts and suffocates. The late Charles Darwin was fascinated by this behavior, and wrote extensively on the now-extinct tapirs he encountered in the Galapagos Islands, giving a first-person account of the day to day life of the animal.

| “ | The tapir, a humble, gentle creature, was spending all the day long nibbling on things upon the hill by the sea, but became frantic at the first smell of rain in the air. As the clouds formed above, the animal began to wheeze and whimper. Soon it took off running, with tears in its eyes, squealing and crying as it went; dozens of others appeared suddenly from the woods around me and fled to safety at the top of the hill as the rain began to fall. The animals, in their panic, slipped and fell one after the other as the rain receded, the fallen being crushed by those coming up from behind. Soon many hundreds of the beasts lay sprawled out dead at the base of the hill, having tripped and fallen on the slippery hillside and broken their necks against the many small rocks they so seemed to adore. As the rain blew over, it was soon apparent that almost every tapir on the island had fallen dead due to what amounted to nothing more than a slight drizzle. | ” |

But doesn't moss only grow in damp locations where it rains often?

This is true, and it causes incredible difficulty to the tapir nearly every day. The tapir needs to eat moss, but if it is raining it must go without. A prolonged period of rainy weather, even if it is only in brief showers, can decimate tapir populations, because even in the unlikely chance that the tapir has survived the first rainstorm, it takes at least a week to recover from the stress the rain caused and to begin feeding again; if frightened by rain in between, the tapir must start the cycle over again, sometimes for months. Eventually, this alone can makes the tapir become dead, which although not invariably fatal, is very unhealthy for any animal, especially the rabbit, but the tapir as well. It is also unfortunate that the more rain that falls, the faster and lusher the moss will grow. In fact, if too many tapirs die off, the moss rapidly reaches plague-like proportions, and soon every stick, pebble, and blade of grass is buried beneath a six-foot deep layer of the stuff, and the forest is choked of life until tapir populations can rebound during the next dry spell and crop it down once more.

Puddles

Quite unlike rain, puddles make tapirs giddy with joy. Two tapirs will fight to the death to gain the opportunity to look at one. But tapirs do not enjoy ponds and even less so lakes, which do not bring out intense fear but rather seething anger. Shown even a picture of a pond, let alone a lake, a tapir will become enraged and may not regain its composure for a year or more.

Reproduction

Tapirs are very shy, bashful creatures when it comes to copulation, and a female will only consent to a male's advances if he earns her trust by bringing her beautiful things like sticks or pieces of bark for her to lick. Sometimes, a male gets lucky and his chosen mate is content with just one or two small twigs, while others fail to please their female even after gifting her with dozens of the largest branches in the forest. Eventually, however, the female will either permit him to mount her, or will brutally remove his genitals with her tusks. In the rare case that the former occurs, the male is allowed to insert either one or (more rarely) both of his eleven-foot-long penises (and sometimes even the third smaller one, as well), and the pair join in coitus for up to an hour.

If all goes well, a single calf will be born the following spring, after an eight month gestation period. The young tapir is born fluffy like a dish towel and pale white like a white mop or a black coat covered in white chalk, and also has numerous brown speckles like a soda can covered in paint splotches, or perhaps a cheetah. The male, a brutish, ferocious animal by nature, does not show any affection to his calf or its mother, and often kills them both violently with his talons if he comes across them in the forest outside of the mating season. The mother shows a little bit less interest in her baby, and does not actively try to kill it most of the time, unless she is drunk. The calf, only a few ounces at birth, grows quickly and is sexually mature by 4 months of age, when it is about 35 pounds, though it may not attain its full adult size for another 3 decades.

| Featured version: 24 December 2012 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |