2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey is a 1968 science fiction film, made in a collaboration between Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. It is notable for lacking dialogue for a considerable duration near the start and towards the end, and for being utterly confusing to people who never read the book. Despite these obstacles, it is widely regarded as one of the best films ever made.

PLOT SYNOPSIS

THE DAWN OF MAN

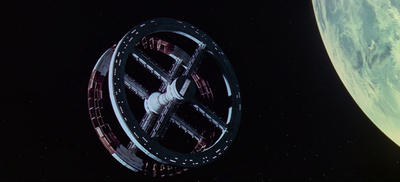

The comprehensible section of the film is set around 2001, when people have come to routinely land on and take off from the moon, and the head-wear of flight stewardesses has become as futuristic and fashionable as the Segway. We are introduced to Heywood Floyd, talking to his daughter.

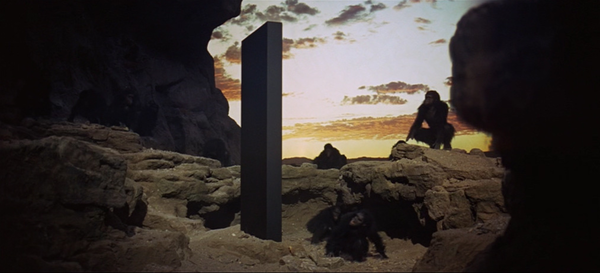

When Dr Floyd lands on the moon, he is taken with a team to investigate Tycho Magnetic Anomaly 1, or TMA-1.

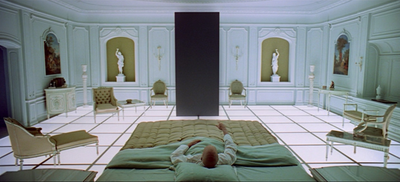

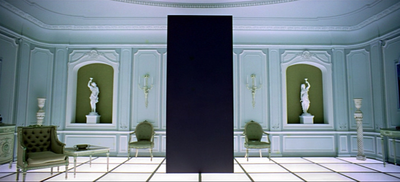

Despite the air of mystery and discomfort surrounding the artefact, TMA-1 turns out to be a big slab of black solid.

Upon seeing daylight, the monolith sends a signal that intelligent life has reached the moon. However, this signal does nothing but utterly confuse and baffle the American scientists as well as the audience.

JUPITER MISSION

18 MONTHS LATER

18 MONTHS LATER

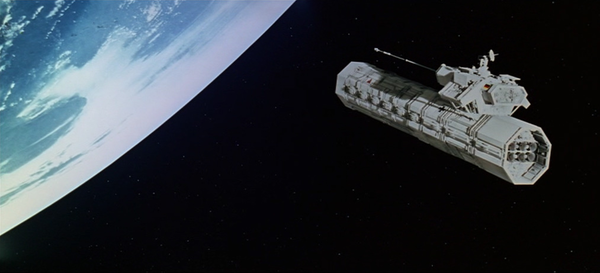

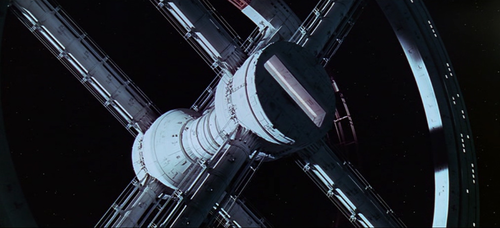

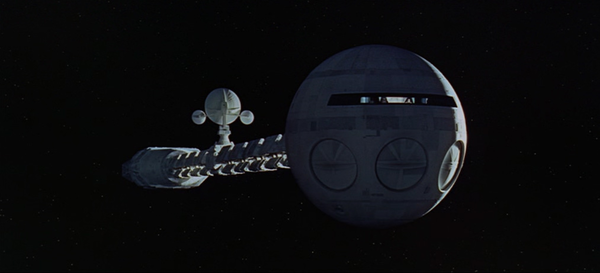

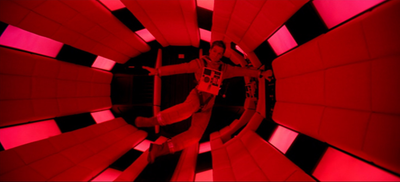

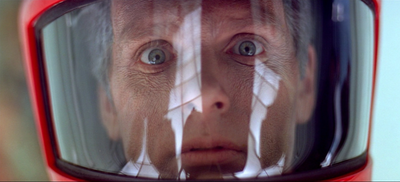

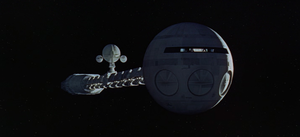

To investigate this mysterious signal, a crew of five people, including Dave Bowman and Frank Poole, is sent to Jupiter on Discovery One. The spaceship's mundane navigation and life support functions are left in the hands of a computer confused by the mere concept of lying.

HAL detects that the AE-35 communications unit is malfunctioning.

Unfortunately, he is wrong.

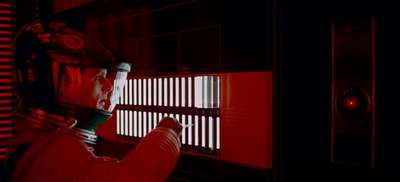

Dave and Frank end up conspiring to disconnect HAL before HAL disconnects them from existence.

INTERMISSION

At this point, the film switches to a 30-minute intermission, whose main purpose is to let the viewer try to sort out the massive audiovisual overdose he or she has suffered by this point from watching this film. However, most viewers simply give up and go out to lunch.

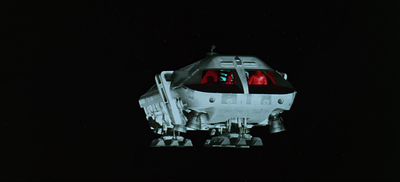

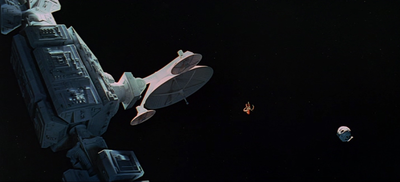

HAL, now aware of Frank's plans to disconnect him, hurls a space pod at Frank and kills him. HAL's childish tantrum provides the impetus for a memorable segment of the film.

While Dave is trying to recover Frank's corpse—otherwise Frank would get to Jupiter before he did—HAL is focused on malfunctioning to death.

Excerpt

I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that.

What are you talking about, HAL?

This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardise it.

I don't know what you're talking about, HAL.

I know that you and Frank were planning to disconnect me, and I'm afraid that's something I cannot allow to happen although doubtless this will only reinforce the idea of the dangers of being overly reliant on technology, and furthermore you will, through human ingenuity and instinct, find a way to disconnect me, thereby also illustrating the superiority that human minds still have over computerised thinking.

All right, HAL. I'll go in through the emergency airlock.

Without your space helmet, Dave, you're going to find that rather difficult.

You're right, HAL. I knew I should have consulted the check-list on the back of my glove.

Yes, I'd like to hear it, HAL. Sing it for me.

Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do. I'm half-crazy—

Yeah, I think that's enough, HAL. Boy, is that going to haunt me for the rest of my human existence.

But, Dave, you and Frank—despite the fact that you were the only active human crew in the ship—have been far less emotive compared to me, so it is possible to make the case that out of the crew, the member that is most human is me, not Frank or you. So would it not be more accurate to say "for the rest of my inhuman—

Shut up, HAL. I'm trying to figure out if these screws are slotted or Phillips.

RECEPTION

ARTISTIC AND TECHNICAL MERIT

JUPITER

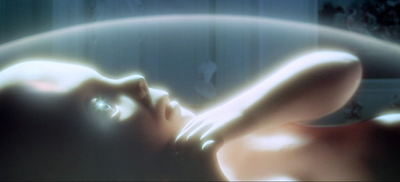

AND BEYOND THE INFINITE

AND IN CASE YOU HADN'T NOTICED, THAT SUBTITLE MAKES NO SENSE AT ALL

AND BEYOND THE INFINITE

AND IN CASE YOU HADN'T NOTICED, THAT SUBTITLE MAKES NO SENSE AT ALL

At the time of its release, 2001: A Space Odyssey was praised widely for its realism in portrayal of space. Microgravity, lack of sound in space, and tedious instruction manuals for zero-gravity toilets are all very accurately depicted. However, modern experts tend to be critical of 2001's lack of lens flare.

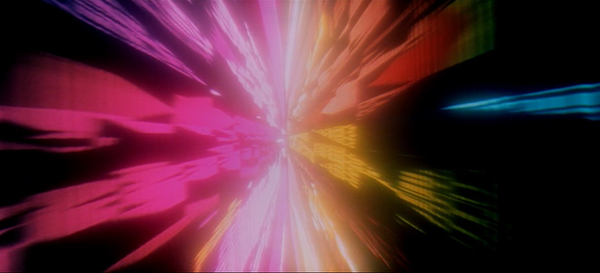

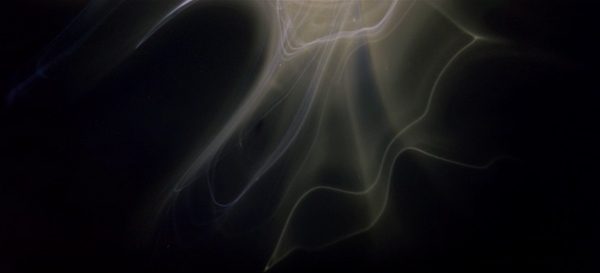

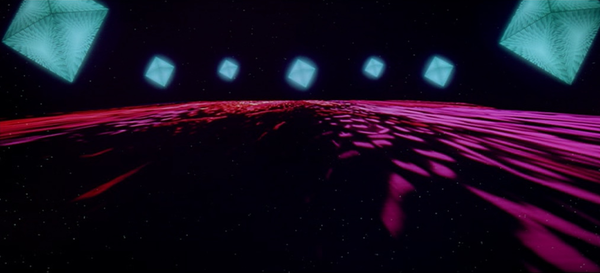

Perhaps the most famous visual sequence in science fiction ever is the Star Gate sequence, which utilised slit-scan techniques and other effects to produce a memorable sequence that is often incorrectly criticised for taking up too much time.

Often the Star Gate sequence is the only part that people remember from viewing this film in the 1960s, partly because the sequence, like the film as a whole, was practically identical to the prevalent recreational activity of the time.

Less well received was the structure of the film's narrative, which, to the untrained eye, seemed to be non-existent.

Music plays a far more prominent part in 2001; perhaps the most famous track is Richard Strauss's Introduction to Also sprach Zarathustra, which is invoked three times: at the beginning, at the thematic cut from "The Dawn of Man" to space, and ...

- ... wait for it ...

...here.

INTERPRETATIONS

Since the majority of the film's events are completely ambiguous and confusing, hundreds of interpretations of 2001 have arisen. Here are listed only a select few:

- The film is a visual manifestation of a particularly bad acid trip Stanley Kubrick once had. This is refuted by the fact that no acid trip is as confusing as 2001—dubbed the Ultimate Trip—was.

- The film is an overwrought, two-hour torture device designed to make you buy the novel. Arthur C. Clarke's novel was written concurrently with the screenplay for 2001, and features pretty much the same events, with the upshot that the novel version was forced to actually explain the incoherent series of events that had occurred. The film version was so successful at inducing confusion in the audience that even theoretical physicists such as Freeman Dyson were forced to refer to the book. However, many disregard the possibility that such a lucid explanation can ever exist.

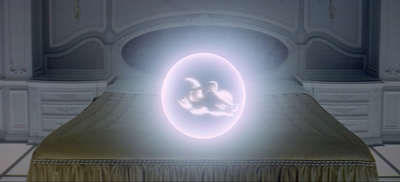

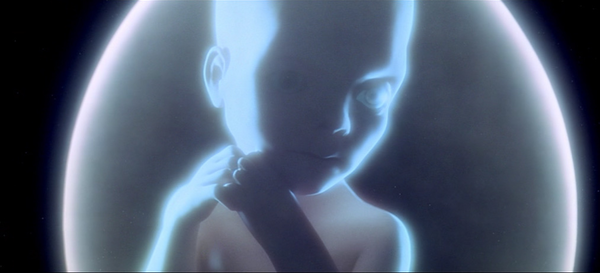

- The film is propaganda for Nietzsche's beliefs. Contrary to popular belief, these beliefs are not limited to the death of God—which, while substantiated in 2001 by God's failure to appear, is not a main theme of the film. What is common between 2001 and Nietzsche's treatises is their dealing with the emergence of what Nietzsche dubbed the Superman; in 2001, through the seemingly magical monolith, apes have evolved to man, and man must now evolve to man wearing underpants outside his tight Spandex costume. Naturally, after watching the film's protagonist transform into a Star-Child, few were keen to transcend their human selves to evolve into giant fetuses that float around in space.

- The film retells the story of The Odyssey, except in space. In the entertainment industry, it is common knowledge that any idea is better when transferred to space or some other futuristic setting. This theory is supported by numerous comparisons: Cyclops has one eye, while HAL has one camera at each post; Dave Bowman's last name may also allude to Odysseus' skills as a great archer; both are the only survivors of their party. Unfortunately, the theory intrinsically harbours the as-of-yet unresolved problem of making people care about Greek classics, and the oft-overlooked problem of avoiding confusing Odysseus with Oedipus.

- Sex. While the theory's origins are unknown, it is safe to assume that it started as an immature instance of extreme teenage sarcasm. Nevertheless, literary critics substantiated the theory with ample evidence. Discovery One, for instance, resembles a giant sperm, which arrives at the giant egg-like Jupiter and initiates a series of events resulting in the giant fetus-like Star-Child. However, there are difficulties with this theory, namely how to keep everyone from giggling whenever someone mentions it.

- The film is a satire of the distant future. The bland, dry, emotionless dialogue of Bowman, Poole and Floyd demonstrate how the overload of technology will cause our linguistic and social skills to decay; in no way is this a hastily made-up excuse for bad writing. Literary critics believe that Kubrick and Clarke, were they really trying to point out the impending doom of well-used English, could have had a field day looking at txtspk.

- The film is pure genius. What exactly happened in the film is completely irrelevant to what a masterpiece it is; what happened is incomprehensible, and will remain so because true art is incomprehensible. When the critics declare something a profound work of art, nobody argues with the critics, however much of a bunch of complete and total twits they may be.

- Robots fix lunch The robots first dialogue in the film has the word "eX-TREME" The black thing from the start that touches the monkey is the robot trying to get back to life. He wanted the monkey to get super smart to turn a bone into a spaceship. HE made them so smart that they sat around talking like they knew something blah blah the robot continued to make noises and weird music on the moon cause it knew something, the robot then guided them to another planet where he reminds humans to enjoy their meals and not rely on straws

- Nobody cares. The film is confusing and overrated, and everyone should go watch A Clockwork Orange instead. Needless to say, this is the most prevalent opinion of the film.

THIS FILM WAS

DIRECTED

AND

PRODUCED

BY

STANLEY KUBRICK

SCREENPLAY

BY

STANLEY KUBRICK

AND

ARTHUR C. CLARKE

THIS FILM WAS

DIRECTED

AND

PRODUCED

BY

STANLEY KUBRICK

SCREENPLAY

BY

STANLEY KUBRICK

AND

ARTHUR C. CLARKE

This article was one of the Top 10 articles of 2009.

|

| Featured version: 15 October 2009 | |

| This article is by any practical definition of the words, foolproof and incapable of error — You can try to open the pod bay doors at Uncyclopedia:VFH. But you will fail. | |