South American dreadnought race

The South American dreadnought race was a naval arms race around the whole of South America between the nations of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Bolivia and the territorial colony of the Falkland Islands. The race was held in the period building up to World War I when the five nations had some spare, suspiciously bought dreadnoughts lying about.

The race is internationally recognised as the point that turned South America, on maps and in the minds of yachtsmen, from a small, insignificant continent into a large, insignificant continent. It still holds the world record for the longest dreadnought race ever held.

Precursors

During the 1880s and 1890s, there had been a few smaller naval competitions between Brazil, Chile and Argentina. These had been decided by the rules of the game "Battleship." Chile suprisingly had won two games and Argentina had won one. However, Argentina was accused of cheating, as Chile claimed Argentina had moved the ships on the board just after each time Chile scored a direct hit. This move became known as the "the hand-of-God" move. ("Post-moves" remain free of controversy when playing "Risk.")

When the dreadnought was invented, the combatants realised they would have to have 6 ships (instead of the conventional 5) on each team to play the game with. At that point, the 8x8 grid became inadequate. Thus it was that South America was pressed into service as a replacement.

The 1906 dreadnought race was further provoked when the Brazilian navy, realising that it was lagging behind technologically, challenged the Argentinians and Chileans to a race with the dreadnoughts. Thanks to excess coffee plantations, the Brazilians expected to win easily and become the greatest naval power in South America. All they had to do was give each sailor extra coffee rations and the caffeine would keep him working hard all day.

The race

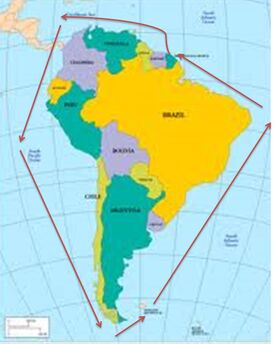

Course

As France had not built dreadnoughts but cruise ships with large dance floors, French Guiana was a neutral country that served as both the start and finish line. The race was set as a single lap, the ships keeping land to their port side. Several last-minute substitutions occurred:

- The British demanded that they take part in the race, as their colony of the Falkland Islands meant that the most powerful navy "in South America" was the Royal Navy.

- The Bolivian Navy intended to participate but dropped out when they realised that there was no way to transport any of their new dreadnoughts to the ocean. The claim of "unforeseen circumstances" lives on to this day, as Bolivian steel and concrete factories are built on influential citizens' land holdings nowhere near any point on the national rail network.

- Uruguay responded to the call to race with a prolonged wail, as it realised it hadn't got a navy.

- Peru also intended to participate, but its premier naval bases had by then already become inaccessible without a stop at Chilean Customs. One can argue that Chile competed on behalf of both nations, but in the interest of economy, it flew only its own flag.

Start

On 14th August 1906, 3 Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 3 British Dreadnoughts, 3 Argentinian Dreadnoughts, 3 Chilean fishing boats labelled "Dreadnought" and unbeknownst to all 1 German U-Boat steamed out of French Guiana.

As soon as the ships rounded the headland and were out of sight of the judges, Advanced Play began. The British declared that the sea extending 50 miles off the coast of British Guiana was British waters, and any foreign ship passing through would be committing an act of war. This sent all other competitors on a giant detour while the British ships sailed straight through, likewise the U-boat. The aggrieved competitors could not retaliate, as there is neither an Argentinian Guiana, a Chilean Guiana nor a Brazilian Guiana.

But Chile also had a trick up its collective sleeve, an unauthorised powdered fuel additive that even today we describe with the country's name. Mixing this "Chilli" powder into the fuel added 3 knots to the speed. Argentina could only counter with natural arrogance (which we likewise describe with that country's name) to convince themselves that their navy was mejor.

Caribbean Sea - Panama Canal

The "sovereign waters" gambit gave the British a 70-mile lead on the other ships. But they lost that lead in Venezuelan waters, when they pursued some drug pirates at the request of local law enforcement.

When the fleet neared the Bermuda Triangle, controversy again reared its balding pate. The Argentinians seemed to be using oars to increase their speed, a no-no even in an arms race. Naturally, the Brazilians opened fire on the Argentinians, sinking one of the vessels.

The Chilean trawlers slipped past unnoticed, but the gunplay ended when the British arrived, seemingly ready to settle matters. In actual fact, the British had mistaken the cannon-fire for English football fans celebrating a victory against Trinidad and Tobago with party poppers. When the British saw there had actually been a battle, they opted for appeasement and thus did nothing.

Soon after, a Brazilian dreadnought mysteriously disappeared on the edge of the Bermuda Triangle — according to locals, another victim of the kraken.

The chicane of this racecourse was the Panama Canal, and the natural result was chicanery, as the Argentinians didn't follow single file but used their foghorns to rouse the sleeping Panamanians on shore in hopes that they would bombard the other ships. One British ship was indeed blown apart and the Captain prepared to go down with the crew. But he saw a marijuana plantation on the coast and jumped off and swam over to attempt to colonise the region.

Pacific Ocean - Galapagos Islands

The next obstacle on the course was the Pacific Ocean's Ring of Fire, a mystical piece of Mayan architecture involving an upright ring of stone constantly on fire (hence the name). While a mere test of navigational prowess for the steel-clad ships, it was fateful for the wooden Chilean entries. When the first Chilean trawler was burnt to a crisp, its teammates, commanded by Commodore Rosie Ruiz, lagged behind until their competitors were out of sight and sailed around the ring instead.

Now dispersed, the ships sailed South towards the Galapagos Islands for their first "pit stop." The rough seas further spread out the ships until they were well out of earshot from one another. This allowed the German U-Boat, which had been creeping along behind them, to isolate and target the British ships. Unfortunately, the U-Boat instead sank one of the Brazilian dreadnoughts. The Captain of the U-Boat was so flustered by his un-Prussian blunder that he sailed straight onto a reef of the Galapagos Islands, knocking off an iguana who was nesting on a rock. The wreckage and the oil spill from the event took three weeks to clear, despite help from the local Greenpeace chapter, which donated many tasty "burgers" to suffering natives who had been inconvenienced, though the bodies of the sailors were curiously not found inside the U-Boat.

When the race reached the Galapagos Islands, the sailors barely had time for a break as the ships had developed a new faster pit stop method that took under 5 hours - a considerable achievement in Naval Arms Race history. First out of the pit lane was the remaining Brazilian ship, closely followed by an Argentinian.

Cape Horn - South Atlantic

The remaining competitors rounded Cape Horn, battered and contemplating suicide, as the food had run out. The weather turned heavy and the Argentinians rafted their two surviving dreadnoughts together for stability. This actually produced instability, as one ship had conserved its rations better than the other. That side sailed lower in the water, even before the crew of the other ship crossed over to raid the galley, directly disobeying the orders of Captain El Hambre. In the resulting mutiny, 124 sailors perished, apparently drowning in porridge, which had spilt all over the decks thanks to a large, weather-induced violent uprising. The surviving Argentinians, commanded by a Señor Buen Provecho, sailed a single ship toward the finish.

Meanwhile, the Chileans, also noting the fierce turn in the weather, scampered back home rather than facing the storm in their small trawlers. Chile would deny ever participating in the race, claiming their fishing boats merely served as "good seats" for the competition.

This left one Argentinian, one Brazilian and two British dreadnoughts. They chugged along toward the next refueling stop, the Falkland Islands. This caused a slight dilemma, as the South Americans had forgotten when setting the race course that the Falklands were British territory. Argentina offered a convoluted defence involving foreign-language place names, but to no avail. The British denied entry to the other ships, while making ample use of the facilities themselves. This was a Pyrrhic victory, as the Argentinians and Brazilians sailed on, while the Brits dallied in comfort until the race was long over.

In fact, the Argentinians implemented a blockade of the islands that knocked the British out of the race more completely than the warm, flat beer served in the island's pubs.

Finish

The Argentinian ship opened up a 2-kilometre lead on the Brazilian as they sailed around the latter's home turf, as the Brazilian had to pause often for photographs with natives who had never seen a steel ship. The only way for the Brazilians to close the gap was drug overdoses. This was effective, as it often is, and the two finishers reached the French Guiana finish line were neck and neck (or rather, bow and bow).

Unfortunately, both desperate ships ignored the harbourmaster's instructions to enter behind an Italian cruise ship. The three ships entered together, the South Americans having gotten word that some of the Italians were sunbathing in the nude. Thus all three ships ran aground at the same time. The Italian captain discreetly abandoned ship just before an explosion blew all three ships to smithereens, as they say in cartoons. The race promoters announced that the arms race had been abandoned due to "adverse weather conditions."

Aftermath

Due to the huge expenditure and loss of life, the International Naval Race Committee called off all future arms races in South America. The severe weather and ruthlessness of the South Americans meant that dreadnoughts were too primitive a technology. From then on, the South Americans stuck to pirate ships controlled by drug lords racing around the Islands of the Caribbean.

Border disputes and other squabbles are now referred to a panel of "Guarantor Nations," which mostly guarantee South Americans access to North American hospitals, housing projects, and supermarkets.

The British, for their part, held one modern naval arms race with the Argentinians, in 1982. The goal of this was to see which country could race its navy to the Falkland Islands first. The Argentinians actually won the race: It turned out, much to the surprise of the average Brit, that the Falkland Islands were nearer Argentina than Britain. Frustrated by this, the British declared that the Argentinians had deliberately moved the Falklands nearer to Argentina. On those grounds, when the Royal Navy did finally arrive, it sank the Argentinian fleet and sent the Argentinian Army (who had tagged along for the banter) home. To this day, the British still claim that Argentinian cheaters moved the finish line, despite strong geological evidence to suggest otherwise.

See Also

| Featured version: 24 December 2013 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |