Constantine VII

“Have you seen my card index box? It's quite a scream”

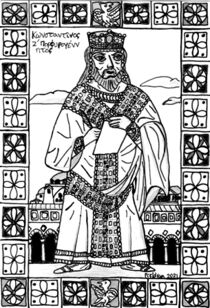

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (17/18 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the Byzantine Emperor from 913 to 959, and the author of one of the most tedious books to have survived the Dark Ages. Constantine spent most of his time writing the Book of Ceremonies — a coma-inducing description of the minutiae of court life in Constantinople in the 10th century. Like: How low should a courtier bow? and How to correctly wear silk pajamas in bed? This book is so incredibly dull that there is no complete translation of it to English. You have to rely on German scholars to supply you with their copy of the same work. That is, if you can read German.

Yet, for being such a bore, Constantine VII's reign is considered to be a 'success' in the history of the Eastern Roman Empire. Though there were a few wars with the Bulgarians that got dangerous, the empire's borders in the East were stable and faced no major threat from the traditional enemies in Baghdad, partly because the Abbasid Empire was breaking apart. Not that Constantine was that interested in re-taking long lost territories — or indeed being much of an active emperor in the traditional sense. He was a writer, a compiler and a collector of tall tales. In other words...a crashing bore.

Constantine VII's work may be the sole reason that 'Byzantine', when applied to writing (especially instruction books and statutes) has come to mean something that is complex, conspiratorial, inscrutable and interminable.

Early years[edit]

Constantine was the only surviving son of emperor Leo VI and Zoe Karbonopsina. Since his parents weren't married, Constantine was a 'bastard' by the niceties of the time. To make his birth 'appear' more legitimate, Zoe gave birth in the Imperial Palace's 'purple room' — a chamber made of porphry marble and supplied with matching colour-coordinated towels. Emperor Leo recognised Constantine as his son and made him a co-emperor shortly after. Then, over the objections of the Byzantine Church, Leo made Zoe his fourth wife, retroactively legitimising Constantine, though his inscribed name, Constantine Porphyrogenitus ('Born in the Purple Room'),[1] suggested that his royal blood owed more to the location of his birth than to any actual fitness.

The church said Leo's latest marital merry-go-round was sinful. Also upset was Leo's younger brother and Constantine's uncle Alexander. He was the official junior co-emperor with Leo and felt his brother should have consulted with him before reducing his share of the throne from one-half to one-third. Things got intense and difficult. Leo sacked the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nicholas Mystikos (Mystic Nick), and replaced him with another called Euthymios. For an encore, Leo died. Constantine was seven.

Imperial regency[edit]

No sooner had Leo's head hit the coffin than Alexander hit the throne. He restored 'Mystic Nick' as Patriarch and appointed his own cronies into lucrative posts. He was also on the lookout for a wife as well. This could result in an heir — and Constantine visiting the imperial opticians to have his eyeballs removed. Though technically still a co-emperor, Constantine was excluded from all palace business and told to play in front of chariots. Then Alexander suddenly died, a demise brought on when the Bulgarians invaded the Byzantine Empire looking for their annual bribe to stay quiet.

The timely death of his uncle made Constantine the sole ruler of the empire. He was still too young to rule anything beyond a game of jacks, so Patriarch 'Nick' took control, swiftly morphing from an opponent of Constantine to the official regent for the short-trousered emperor — but it was short-lived. The Bulgarians were still awaiting satisfaction, and would no longer be satisfied with the usual payoff. Their leader Symeon demanded the Byzantines treat him as an equal, with the title of Tsar. In response, Mystic Nick did — nothing. As a consequence, he was sacked as regent but kept his job as Patriarch. Constantine's mother, Zoe Karbonopsina, took back official control in her son's name.

Romanos washes in[edit]

Alas, Zoe was as all-thumbs at war and diplomacy as Mystic Nick. Her generals' dismal showing against the Bulgarians led to another coup in 919, this time led by a Byzantine admiral called Romanos Lekapenos (Greek for Leaky Penis, known to posterity as Incontinentia). Romanos got the backing of Mystic Nick, who was keen to get revenge on Zoe. She was exiled and never saw her son again. Constantine was placed in the rough hands of the scurvy scarred sailor.

Within two years, Romanos had fast-tracked himself to become the senior emperor in Byzantium. Constantine was relegated to a back seat and 'obliged' to marry Romanos's daughter Helena Lekapene. Her brothers Christopher, Stephanos and Constantine Lekapenos all received imperial promotion and their own wings in the imperial palace[2]

So, at the age of 15, Constantine VII found himself a stranger in his own palace, with ample basis to fear for his life or extremities. Romanos felt that depriving his son-in-law of all actual power was like a 'soft castration', and perhaps the Byzantines were losing their fondness for physical mutilation of their emperors. Constantine was allowed to keep both eyes and both testicles. In return, he asked for nothing but his library card, as he reverted to reading and writing boring manuscripts.

Writing[edit]

Constantine spent the next 25 years rummaging through codexes, looking at crude drawings, and deciphering questionable margin scribblings. In the massive gap between his two stints at statecraft, he did pop into to see his wife at least six times to produce five girls; also a son, named Romanos in honour of his grandfather. Once his bedroom duties were over, Constantine quickly nipped back to his books.

Several of Constantine's books have survived. They are (using their Latin titles):

- De Thematibus (The Themes) — Byzantine local government. Bring out the matchsticks for your eyelids as you try to stay awake.

- De administrando imperio (Imperial Administration) — Byzantine bureaucracy made difficult.

- De cerimoniis aulae Byzantinae (Ceremonies) — A Byzantine manual about the laborious court ceremony designed to waste people a lot of time, but also to bamboozle visiting Franks, amongst others.

- All About Basil — Constantine's bilious biography of his grandfather, emperor Basil I. A readable book about how a semi-literate horse rider rose from cleaning out the emperor's chariot to becoming one himself (an emperor, that is).

- How to self-medicate after a fierce battle — Historians dispute whether this is by Constantine, as it is even more boring than the rest.

Constantine doesn't say much about himself and seems to have had an image issue. He was reported by a visitor from the West to be 'extraordinary ugly for someone so exalted'. The books may be largely dull and dusty but have provided a lot of work for Byzantine scholars.

The reclusive emperor had a lot more book ideas, but between 944 and 945, experienced an unexpectated change in fortune. He would be given the chance to be a ruler in practice as well as theory.

Now rule as a Caesar[edit]

Constantine's father-in-law Romanos I had held the Byzantine Empire in a vise grip for nearly 25 years. He 'arranged' to have his youngest son Theophylact enthroned as Patriarch of Constantinople to fill a vacancy. The boy was barely 16 and had shown zero interest in taking Holy Orders before, but he agreed to be gelded to receive his patriarchal hat.

Yet not everyone was happy. Constantine's brother-in-laws Stephanos and Constantine Lekapenos grew impatient that their father insisted on keeping all the real power. Despite leaving manuscripts lying around the imperial palace extolling the wonders of retirement and long ship cruises, the brothers failed to persuade Romanos to resign. So, in 944, Stephanos and Constantine Lekapenos, with the complicity of the imperial guard, deposed Romanos and sent him off to an island exile.

Their obvious next step would be to target Constantine VII and his family, but their sister Helena Lekapene struck back and deposed them in turn. Stephen and Constantine Lekapenos were sent to the same island as their father. This bit of palace drama left Constantine as sole ruler. Now the job was to find him to break the news. Constantine was found in the library fast asleep under a mountain of manuscripts.

Constantine did a few imperial things, like entertaining the ambassadors sent by King Otto of Germany (later Holy Roman Emperor) and the Abbasid Caliph Abd ar-Rahman III. However, he left the day-to-day emperor stuff to his wife Helena. She cleaned out the imperial palace and called in redecorators. She was another of these ruthless woman emperors the Byzantines were good at producing. Blood is supposed to be 'thicker than water', but she had her nephew Romanos (son of exiled emperor Stephanos) castrated and her brother Constantine Lekapenos killed when he tried to row away from his island prison.

Likewise, Constantine let his soldiers decide which battles to fight. One of them, Nikephoros Phokas (a future emperor) earned his golden riding spurs with victories against enemies both West and East. Constantine himself didn't fight, having an aversion to loud noises.

Death[edit]

Constantine VII died in 959. It was rumoured his demise was 'accelerated' by his ever-impatient daughter-in-law Theophano with the help of slow-acting poison, then a fast-acting bludgeon. Constantine's wife Helena failed to protect him from Theophano this time around. She was shoved into a nunnery, along with Constantine's many daughters.

The late emperor's book collection was copied and passed around so that it finally ended up in Western Europe. Other European monarchs ordered their copies, keen to imitate the Byzantine methods of impressing simple folk. Copious notes were taken.

References[edit]

| Preceded by: Alexander |

Byzantine Emperor 913–959 |

Succeeded by: Romanos II |