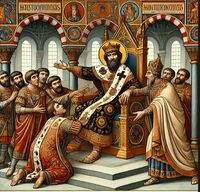

Michael VI

Byzantine emperor Michael VI Bringas (Greek: Μιχαήλ Βρίγγας; died c. 1057) preceded American general Dwight D. Eisenhower by 900 years, but had one thing in common: Despite their official rank, neither ever got dirty or sweaty in actual combat. The organiser of D Day managed to be always in the wrong place at the right time.

Eisenhower's lack of experience at a front line always hindered 'Ike' during arguments about issues like the Military-Industrial Complex. Michael VI likewise was never a real general, spending most of his time in an office filling out forms and licking stamps. The way he arrived at the top slot in the Byzantine empire was, in a word, bureaucracy — or, in two words, Byzantine bureaucracy. Doubly bad and very byzantine, clever enough to bamboozle uncouth barbarians dressed in animal skins and the thick 'Franks' in their full metal jackets. It could all become very confusing and twisted as the ends defeated the aims as Michael VI discovered.

Background[edit]

An additional key to Michael's ascension was empress Theodora. Having ruled the Byzantine empire first with her own sister empress Zoe and brother-in-law emperor Constantine IX since 1042, by 1054 she was soloing. Her dynasty was about to go extinct. There were no living relatives to claim the throne. When she was about to croak in 1056, her advisors put forward a candidate to bridge the divide between quill-pushers and warriors. Michael fulfilled the first category and claimed that working in the Byzantine equivalent of the Veterans Administration enabled him 'to understand soldiers and their needs'.[1]

However, there was a rival; a nephew of Constantine IX called Theodosios stirred up the mob in Constantinople and opened the prisons to advance his claims. They marched to the imperial palace, where Theodosios claimed empress Theodora had promised to pass on the imperial crown to him and that her wishes had been subverted. The palace doors remained shut, so Theodosios attempted to gain access to the Hagia Sophia, but was stopped by the Patriarch Michael Keroularios. By now the would-be emperor's supporters had deserted and he was arrested. Usually, this would lead to a swift execution, but Michael was feeling generous. Theodosios was banished to a provincial exile and told to never to come back to Constantinople. He didn't. The aborted putsch relieved fears that Theodora's death would spark a civil war.

Emperor Michael versus Patriarch Michael[edit]

The real power in the land was Patriarch Michael Keroularios. He had been instrumental in the break with Catholic Rome in 1054, the Great Schism. Like the other bureaucrats, he hated to spend money on the military, preferring that the empire boost spending on church projects, notably, a rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which had been trashed by a crazed Muslim ruler earlier in the century.

Emperor Michael VI was already in his late 50s and out of shape after all his long hours sitting behind a desk. Civil servants began referring to him as Michael Stratiotikos — 'Michael the Warlike'? This reflects a cruel Constantinople sense of humor; the emperor had no experience lopping off the heads of the enemies of the Byzantine empire, nor the gumption to acquire any, either.

Nor had Michael VI any idea how to deal with uppity generals. His primary opponent was Nikephoros Bryennios, who had been exiled earlier in a complicated plot to prevent Theodora becoming sole empress. Michael allowed him back to the imperial court, minus his confiscated estates. If Nikephoros were cautious, he would have bided his time to return to full favour, but he promptly raised the flag of revolt — before looking to his generals for consensus. They vetoed the rebellion, and then vetoed both of his eyeballs, the traditional method of disabling an imperial claimant.

Rebellion and deposition[edit]

Michael had managed to survive two attempts to depose him, but the third time was a charm. This next rebellion was led by Isaac Komnenos. Fighting on a anti-bureaucrat platform, Isaac marched to Constantinople, brushing aside the army sent against him. Talks broke down to create a duopoly with Michael and Isaac as co-emperors. Once again, Keroularios stepped in, persuading Michael to abdicate with the promise of safe passage to a monastery of his choice, though somehow he was also allowed to turn his own home into a holy retreat. Michael was out of government, after barely a year, in favour of the new Isaac I.

Death[edit]

Promptly after becoming a monk, Michael became a corpse. It may be that the chafing of his monk's habit shocked Michael after the soft, silky clothing of an emperor; or it may be that the promise of safe exile in a monastery was a final deception.

References[edit]

- ↑ There is no record of a Mrs Michael VI to distract him.

| Preceded by: Theodora |

Byzantine Emperor 1056–1057 |

Succeeded by: Isaac I |