Licinius

If even half of what is said about Roman Emperor Licinius (262-325) is true, then this man is responsible for killing a great number of people, among them:

- The wife and daughter of emperor Diocletian.

- The wife and children of emperor Maximinus Daia.

- The sons of emperors Valerius Severus and Galerius.

- Two co-emperors, sacrificed to save his own skin.

Also for cheating at ancient Roman Lotto.

When Licinius died, his rival (and brother-in-law) Constantine the Great had Licinius's name struck from all the historical records, and additionally filed a posthumous charge of paganism, in violation of an edict the living one and the dead one both co-signed in 313 as the respective emperors of the Western and Eastern Roman empires, when they granted the Christians toleration. This turned Licinius into an unperson centuries before George Orwell would even invent the concept.

Romanian[edit]

Licinius was born in Dacia, but ten years later, had to move when arriving Goths desired his home more, and had superior weapons to do something about it. The experience left Licinius with a pathological fear of smudged make-up and chrome bracelets. The family wandered the Balkans until young Licinius grew up, joined the Roman army, learned to wander in formation, and fell in with the roistering, but functionally illiterate, Galerius Gabberous (later Emperor Galerius). Under this protector, Licinius progressed up the ranks. Galerius remained a bachelor and stayed out all nights with his drinking mate, on whom he relied to read the bottle labels before sucking down their contents.

Licinius also benefitted from the partnership. When Galerius became Caesar in 293, Licinius followed him on military campaigns and more jobs followed. When Galerius became Emperor in 306, Licinius manned the open bar for the invitees. So far, he had shown no great skill at anything, except buttering up Galerius. So there was general astonishment when Licinius was given a new job — Emperor, no less, an imperial co-equal of his old mate. Except, of course, there were already three men claming the same title, although Severus, the last one Galerius had promoted, had just committed suicide in jail — according to the coroner, by kicking his own head in.

Emperor of where?[edit]

Licinius's jump to supreme power took effect at a big power meeting at Diocletian's retirement palace in Dalmatia. In theory, it fell to Emperor Licinius to bust his rival Constantine back down to the rank of Caesar. However, Maximian and his son Maxentius were also active Emperors and were giving Licinius the evil eye. The slippery Licinius declined to crack the whip and opted to crack the oar instead, persuading Galerius to give him responsibility for a bit of the frontier along the Danube-Rhine.

Galerius agreed, but got bad stomach cramps whilst chasing Christians around the Roman Empire. His successor in the East, Maximinus Daia, had no special reason to like Licinius and in fact was partial to Maxentius. Licinius now had to choose sides. He allied with Constantine, and went to meet the man he was supposed to overthrow and execute. Can't have been an easy interview.

Alliance with Constantine and with a wife[edit]

The surviving portraits of Licinius, his jowly face, and his beady eyes, suggest he was hardly a prize catch and might not have even inspired confidence with his ally Constantine. However, the "two-Max" alliance was active, and Licinius and Constantine needed to confront them.

Constantine suggested to his annoying sister Constantia that she marry Licinius and create a "marriage bridge." Licinius was willing in principle, although desiring "a final fling at bachelorhood." He was still dithering about it when Constantine went off to Italy to deal with Maxentius. Licinius' task was to move against the other one, Maximinus Daia, but Licinius moved his legions slowly. After all, if Constantine were defeated on his front, Licinius could double back and pick up the pieces (being Gaul and Britannia) for himself.

However, one severed head of Maxentius later, Licinius saw that Constantine had held up his end, and got him thinking about eliminating the maximum amount of "surplus Emperor material." The Process of Elimination apparently got to Diocletian's wife Prisca and his daughter Valeria, the widow of emperor Galerius. He also knocked off Galerius's son Candidianus and even Severianus, the son of the otherwise forgotten emperor Severus. Then it was off to Asia to find Maximinus, but the latter fled and committed suicide. Licinius then added his opponent's wife, daughter, and son to the tally.

Constantine overlooked this "tidying-up" and, in 313, the two issued their Edict of Toleration. The Christians were now off the menu for persecution, their property and lives ensured against future pogroms. Since Constantine had also killed his own nephew, the new partnership — and Licinius's marriage to Constantia — made them imperial blood brothers-in-law. So all should have been peace — except neither man felt comfortable about sharing the Roman power couch.

Licinius makes his move[edit]

In 315, Licinius named his new business partner, Valerius Valens, as co-emperor. This was necessarily a slap at the existing co-emperor, Constantine, and battle was joined at Mardia. Constantine showed an ability to win battles, whereas Licinius's sole skill was buttering people up, and perhaps murdering them. In a puzzling gambit, Licinius chopped up Valerius and delivered him in broiler-ready strips to Constantine. But Licinius's key move was to ask his wife Constantia to do a "pleading song-and-dance number," massaging her belly to remind Constantine that she was heavy with child. The gambit worked; Licinius was spared, provided he "make a bit of a grovel for appearance's sake." Licinius thanked Constantine for his mercy by eating his colleague's old sandals.

Constantia gave birth to a son who was named after his father. Since Constantine had also named his son Crispus a Caesar, Licinius did the same with Licinius Junior — though as an everyday colleague, there wasn't much a two-year-old could contribute to running an empire except shaking a rattle.

Second attempt, and then Curtains[edit]

Relations between the two emperors remained cold but cordial until 320. Licinius had heard reports that still-pagan Constantine's enthusiasm for all things Christian had alienated the Pagan Caucus in Rome's Senate. Since Christianity wasn't the official religion of the empire, the old followers of Jupiter and Hercules were still going to their temples to celebrate various rites. They believed Christianity was a passing fad that would go out with bell-bottom togas and revealing Greek tunics, once youngsters came to their senses.

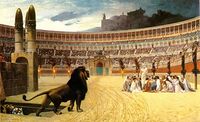

Licinius therefore started some good old-fashioned Christian-burning. This got the notice of Pope Sylvester in Rome. He criticised Constantine for "standing idly by" and urged action. In 324, Constantine marched east and, once again, Licinius raised up another Roman sap to become his new "partner." The current purple-garbed idiot was Sextus Martinianus. The result was as the same as in 315 — except for the differences. Sextus got the literal chop; Licinius & Son got full degradation: their badges broken and their business togas shredded. Eating sandals would not be enough this time. Once again, Constantia appealed for clemency for her husband and son, and Constantine sent the family to Thessalonica.

The next year, Constantine went to Nicaea to offer "management expertise" on theological issues about which he had no clue. However, Licinius's continued existence bothered him and he regretted having shown him mercy. So he detoured to Thessalonica and confronted the disgraced family. Once again, Constantia appealed to her brother's "good Christian nature." However, Constantine pointed out that he was not a Christian. His pagan conscience prompted him to order the execution of Licinius. He added, "No hard feelings, Sis."

This time, there was no mercy for Licinius, and off came his noggin. The younger version was spared for a year, but Licinius Junior died when Constantine also snuffed out his own son Crispus and wife Fulvia. This was another murky episode that Christian historians helpfully avoided writing about.

| Preceded by: Galerius |

Roman Emperor 308-324 |

Succeeded by: Constantine the Great |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||