Knights Hospitaller

“Do you like Hospitaller food?..”

“Black Knights are a Long Way from Home”

The Knights Hospitaller are an order of killer monks, founded in the Holy Land during the Crusades to defend Christianity and smash Islam. They are also called the Knights of St. John, 'The Malteasers,'[1] and The Black Caped Crusaders.[2] The Hospitallers also practised medieval medicine (hence the 'hospital' bit of their name) on patients and prisoners alike. While 'practise makes perfect,' these Hospitallers tended to kill more people than they saved.

The Hospitallers still exist, though they are now niche players. One of their most deadly outfits are the feared St. John's Ambulance,[3] an order of very old men and women who get in to watch sporting fixtures for free and occasionally revive a punter with hot tea. Accidents do happen, and even more occasionally the punter is not revived.

Origins[edit]

The Hospitallers sprang up after the First Crusade sacked Jerusalem in 1099. They pretty much murdered any survivors who couldn't prove they were Christian. Amongst the blood and destruction, a monk called Blessed Gerard set up the order. He had lived in the city when the Muslims ruled it and kept his vows of non-violence, being outnumbered. Now, he sought an elite order of holy soldiers who would combine piety, prayer, and swordplay.

Any high-ranking nobleman could become a Hospitaller and receive a special dispensation to cut down 'the enemies of Christ.' They were independent of kings and princes, swore loyalty to the Pope, and always washed the dishes. Brother Gerard waited fourteen years to receive official recognition, as air mail was still centuries away.

The Hospitallers usually wore black cloaks and surcoats with a white cross stitched on the front, back, and legs. As a fashion variation, some knights preferred a white cross and red dyed tunic.[4] The Hospitallers' great rivals in the fight against the Muslims were the Knights Templar, founded in 1119. The two Orders fought each other (usually without drawing swords) over fundraising and spiritual endorsements, which were lucrative in their own right. Later, the Teutonic Knights began to compete, recruiting Knights who liked German efficiency, spicy sausage, and solid sauerkraut.

We're on Holy Orders[edit]

For the first 90 years, the Hospitallers and the other warrior-monk outfits did what they set out to do: Look after Pilgrims, protect the roads, and exploit the Holy Land. However, in 1187, the Muslim warlord Saladin took Jerusalem and closed in on the remaining Crusader outposts. The arrival of Richard the Lionheart helped recover some territories, but Jerusalem itself was mostly lost, off-limits to Pilgrims unless they got the Muslims' permission to travel. Even in this case, there was no armed guard of sweaty knights protecting them.

Yet the Hospitallers grew rich. Not as much as the Templars, who were in a similar position, but they still earned 'walking-around money' from bequests, granting of lands, and dispensations. In 1291, when the last outposts in Palestine finally fell, the homeless Hospitallers relocated to Cyprus. To add to the humiliation, the Hospitallers and their fellow exiles the Templars had to share lavatories.

Rhodes[edit]

In the early 13th century, the Hospitallers moved again, to the Island of Rhodes, just off the coast of Turkey, which had been part of the Byzantine Empire. They claimed the island as their own, invaded[5] and then fortified it. They also developed their policy of 'holy piracy,' attacking any ships identified as Muslim.

From Rhodes, the knights expanded their empire and escaped the fate of the landless Knights Templar, who were destroyed by King Philip IV of France in 1307. Indeed, the Hospitallers were awarded with the bulk of the Templars' former properties for their tacit support for the suppression of a rival Holy Order. Nor did the Hospitallers give up hope that a new crusade would come their way and restore their former power in the Holy Land, though crusaders instead selected easier foes elsewhere in Europe.

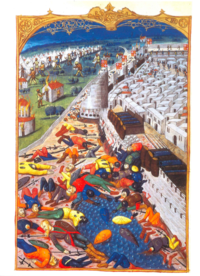

A more immediate threat to the Hospitallers soon came from the Ottoman Turks. Expanding in all directions, they put the squeeze on the Knights at Rhodes. The Siege of 1480 was followed by the Siege of 1522, the difference being that in Siege Two, the Reformation had shattered the unity of Western Christendom, meaning the Knights were in the crapper. They withstood this siege for months, but with no rescue missions to help out, they came to terms with Suleiman the Magnificent. Striving to also be Suleiman the Magnanimous, he let the Hospitallers leave with their armour and suitcases, while the non-knight population were rewarded with slavery. Suleiman would regret this later.

Malta[edit]

Homeless yet again, the Hospitallers drifted around the Mediterranean looking for a safe place to pitch up in. Eventually, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V offered them the islands comprising Malta — barren, compared to the lush greenery of Rhodes, but 'there's no place like home.' Charles also asked them to defend his new conquest of Tripoli in Libya, but that was re-taken. Besides the Turks, the Knights encountered the saucy corsairs known as the Barbary Pirates. They were not much as soldiers but were geniuses at sailing galleys. The Knights had to get the oar in — and quick — to survive here.

Bit by bit, the Hospitallers rebuilt their new home until, Suleiman dropped his 'nice Sultan' act and channeled his Inner Hun, going back on the offensive against the Hospitallers. This time, there would be no let-up. A huge invasion fleet landed on Malta in 1565 to drive the Knights into the sea. The knights' leader this time was Grand Master Jean Valette. He refused to surrender and sent one of the sultan's emissaries back to the Turkish army, via a cannon.

It was a bitter struggle, but eventually the Turks gave up and returned home. Suleiman promised he would return, but never did. The Hospitallers could keep their home.

With the Turks gone, the Knights carried on all the pleasant Crusader traditions, to-wit: warfare and being a general nuisance to the Ottoman Empire. The order still owned plenty of property in Catholic Europe, though their holdings in the Protestant world had been sold off or destroyed. But they were a micro-state, and in the late 18th century, two macro-states — Britain and France — took an interest in the islands.

Homeless and split[edit]

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte of the French Republic landed on the islands en route to his armed holiday in Egypt. The Knights unwisely spat in the soup offered to Napoleon, who in response annexed Malta and helped himself to their treasury. Two years later, Admiral Horatio Nelson took the islands off the French and promised to return them to the Hospitallers 'once the crisis was over.' They never did, and just added them to the British Empire.

The depleted Order wound up in Rome but argued about who should be Grand Master. Czar Paul of Russia claimed the seat. Though a supporter of the Order, he wasn't even a Catholic but a Russian Orthodox, though no one could find any rule prohibiting it. Other Hospitallers thought this ridiculous and fights broke out. Paul was murdered in 1801 and his son Czar Alexander gave the job back to the Pope to sort out. The Hospitallers looked about as relevant as the recently collapsed Holy Roman Empire, a relic of a past age.

What are they doing now?[edit]

The Hospitallers are still active in metro Rome. However, unlike the Popes with the Vatican, the Hospitallers have no sovereign micro-state. They have a 'sovereign house,' a single building in Rome, which technically is a nation, could issue passports, and casts full votes at certain global warming conferences. Unlike the Protestant St. John's Knights, they have given up both medicine and crusading, and only even wear swords on special days. Planning is underway for their 1,000-year anniversary in the year 2099, the biggest uncertainty being whether anyone alive will care to attend.

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ See Chocolate

- ↑ Which makes Batman a latter-day Hospitaller.

- ↑ Though they wear the same crosses and claim descent from the original Hospitallers, strictly speaking they are separate and non-Catholic.

- ↑ The latter colour scheme is seen on the Hospitallers' modern flag.

- ↑ War against other Christians was fine if they were judged heretics and/or schismatics like the Greeks.

| |||||||||||||