John Brown

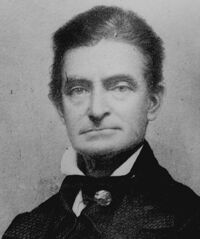

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an abolitionist in the United States who believed armed insurrection was the only way to correct the young nation's faults. He is notorious for his 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry, although the only abolition it achieved was the apostrophe. Following the raid, the United States abolished Brown's pulse (and, much later, slavery).

Historians memorialize Brown as a heroic martyr and a visionary, while others vilify him as a madman and a terrorist, yet another proof that inability of Americans to agree on the most basic facts did not originate with the Presidency of Donald Trump.

Early years

Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut, the fourth of eight children. Brown himself would go on to have a litter of 20. Eleven of these survived dysentery and reached adulthood, where they mostly succumbed to their father's spotty military instincts. Brown followed his brother into the tannery trade, before branching out into the side-business of insurrections.

In 1836, Brown moved to Ohio and started another tannery, along with Zenas Kent, whose own side-business would turn out to be loaning his surname to the city. Brown built the business on state bonds, but the economic crisis of 1839 struck the western states worse than the Panic of 1837, the recession of 1836, the downturn of 1835, the bubble-bursting of 1833, and the depression of 1832. During the Panic of 1837, Brown publicly vowed:

| “ | Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery! | ” |

This was a damned sight nobler than consecrating his life to the destruction of hunger among his brood of 20 hungry mouths. By all accounts, this was the very moment at which Brown became anti-slavery. However, his competitors in the tannery racket had consecrated their lives to ensuring that revenues exceed expenses; and in 1842, an Ohio bankruptcy judge ruled that Brown may have been anti-slavery but was definitely anti-solvency.

Springfield, Massachusetts

Brown sought a new start in Springfield, Massachusetts, a city whose life was already consecrated to the destruction of slavery occurring elsewhere. Springfield was a veritable American Speakers' Corner, hosting rousing speeches by Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. (Slavery is now destroyed and the city has re-consecrated its life to the destruction of small business, excluding pawn shops, liquor stores, and Dunkin Donuts.) Douglass would write about Brown:

| “ | From this night spent with John Brown, while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful for its peaceful abolition. This guy is bat fuck insane! | ” |

Brown, with business partner Simon Perkins, set up an agency to represent Ohio wool growers, winning the hearts and minds of Springfield by opposing its own wool industry. The state's mercantile elite had reacted with hesitation when Brown asked them to change their profitable formula of selling tons of wool at low prices. Brown naïvely trusted them, but soon realized that their "Maybe" was a definite "No": They were determined to make a ton of money. Brown was disappointed to learn that Europe preferred to buy at low prices almost as strongly as Springfield preferred to keep making a ton of money. Brown then traveled to England to appeal to the buyers to pay more for Springfield's wool than Springfield was asking for it. Somehow, the firm lost $40,000 on this campaign and closed in late 1849, though the audience clapped until Brown performed an encore in bankruptcy court.

Back to anti-slavery

Brown now sought bigger fish to fry, especially ones that would not flop around in the skillet and spatter grease about. In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, obliging authorities to return escaped Negroes to their proper owners and penalizing citizens who helped them escape. Brown believed that slaves could be hidden in the Underground Railroad, a spur line beneath the Berkshire Mountains he had proposed that would link Springfield with Albany, New York, which he might have built if he had had two pennies to rub together. Defying this new Act inspired him even more than defying his creditors. He founded a group of militants called the League of Gileadites, named after the Biblical mountain where only the bravest of Israelites would gather to be wiped out by invading armies. He stated:

| “ | Nothing so charmes the American people as personal bravery. [Blacks] would have ten times the number [of white friends than] they now have were they but half as much in earnest to secure their dearest rights as they are to ape the follies and extravagances of their white neighbors, and to indulge in idle show, in ease, and in luxury. | ” |

His audience briefly exchanged baffled looks, then gave a rousing cheer. It was the best motivational speech since Bilbo Baggins told his party guests that he liked only half of them, half as much as they deserved. Brown seemed to be saying that the African American would stop whittlin' in de rockin' chair and whinin' 'bout dem aches and pains, if only white folks provided a motivational goal, such as avoiding imminent death in combat.

Kansas

The United States was adding states faster than McDonald's could build them restaurants, and some of the new states had no clue where they stood on the question of slavery, resulting in a veritable open season for ne'er-do-wells from the East to give them a piece of their minds. Kansas in particular seemed ready to settle the question at the ballot boxes — forty paces apart — with revolvers. Brown saw a boiling cauldron needing nothing more than one more cook. He stopped briefly at an anti-slavery convention, where his violent approach met controversy on the debate floor, but also met financial backers. He picked up weapons and leaflets along the way.

Right after the 1856 spring thaw, Brown's forces believed they could usher Kansas into the Union as a slavery-free state, especially if they ran the place. But the pro-slavery people Brown called "ruffians" would not quit without a fight. Stringfellow wrote:

| “ | We are determined to repel this Northern invasion, and make Kansas a Slave State; though our rivers should be covered with the blood of their victims, and the carcasses of the Abolitionists should be so numerous in the territory as to breed disease and sickness. | ” |

Brown was almost as outraged at the violence expressed by the pro-slavery faction, as at the lack of violence of his own faction, whom he described as "cowards, or worse," dot dot dot. Brown and his family were marked for attack, though Coward Or Worse Charles Robinson stated that "this indictment will hardly justify midnight assassination of all pro-slavery men." Indeed, Brown did not get them all. But he did get 29 over three months in the Pottawatomie Creek Massacre.

Easterners and Missourians fought one another over what was best for Kansas, until who should appear but Governor Geary, with a magnanimous offer not to press any charges, provided everyone just went away.

Brown did return east, later that year. He met with prominent abolitionists and got gobs of cash, 200 rifles, 1000 pikes, and 5000 Bluegills. He stored the weapons in Iowa, which is somewhat close to Kansas. In October, Brown and his army arrived in Kansas — minus his drill instructor, Hugh Forbes, who never got paid and didn't agree with Brown on anything — only to find that Kansas had voted itself slavery-free before Brown could fire a single shot.

Brown's next task was to conduct a Constitutional Convention. He chose Chatham, Ontario for his followers to make motions and amendments and split hairs over Parliamentary rules. Unfortunately, the Convention never agreed on a territory to which the Constitution would apply, Kansas seemingly having sorted out its affairs without Brown's "help." Unlike those other famous Founders, these authors never pledged their "lives, fortunes, and sacred Honor," and in fact, when Forbes threatened to spill the beans, they put the entire prairie fire on the back burner.

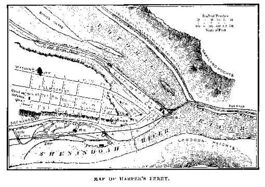

Harpers Ferry

Brown joined with Harriet Tubman and with freed slaves living in Canada, believing that, if they won a first battle, slaves across the south would rise up and rebel, whips and chains somehow being less decisive if there is a trendy new cause in view.

In September 1859, the pikes arrived from Charles Blair, but the Bluegill did not. Moreover, in contrast to his plans for an army of 4,500, Brown amassed twenty-one. On October 16, an undaunted Brown led 18 of them on an attack on Harpers Ferry, intending to capture its 100,000 weapons, give them to Virginia slaves, and hope they were more receptive to Brown's plan of attack than Douglass or Forbes had been. The strength of the idea would cause the entire southern economy to collapse.

As absurd as it was to contemplate 100,000 rifles being snuck away by 18 insurgents, it was more absurd to have them guarded by one night watchman. Brown's forces easily captured the armory and sent word to all nearby slaves to "prepare to be liberated." They intended to set out to the south, "fighting only in self-defense." Unfortunately, an enemy combatant appeared — to-wit, a passenger train of the Baltimore & Ohio line, which had not yet become a stopping-space in Monopoly. Brown sounded the attack. His forces succeeded in killing one person: the baggage master, who was a freed slave. Brown's forces then let the train pass and tell the U.S. Government what was afoot.

Inconceivably, residents and a local militia came to retake the armory and blocked the only escape route. Brown's son Oliver begged his father to end his suffering, but Brown said "If you must die, die like a man." So he did. Within a day, the Marines arrived. Army First Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart told the raiders their lives would be spared if they surrendered. Brown said, "No, I prefer to die here." Instead, the U.S. troops broke down the door and took seven captives, making Brown die somewhere else.

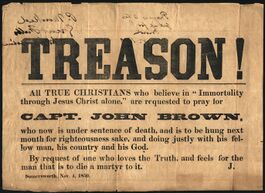

On November 2, a jury found Brown guilty on all three counts, the capital crime of killing 4 white men and the minor misdemeanor of killing the black baggage master. Also, treason. A public hanging was scheduled for December 2. Ralph Waldo Emerson may have remarked that "John Brown will make the gallows glorious like the Cross," but the gallows made John Brown dead like the doorknob.

Legacy

Brown's vision of slaves rising up and throwing off southern state governments was inspiring — throughout the north. It helped inspire the north to impose harsh conditions on the south and, when the south broke off, helped inspire the north to not just let them go away. In the south, many slaves took up arms to defend their own states against the north, the predictability of slavery being preferable to an uncertain future under northern occupation, with house payments and buying the kids school clothes and such. The south adopted several of Brown's tactics, including sneak attacks where you let some of the hostages go and tell everyone what is going on, and use of an inadequate fighting force.

Brown's strategy of futile attacks against random non-combatants to make a social statement, plus refusing to take No for an answer until the entire U.S. military gets called in, became the model for groups from al-Qaeda to ISIS.

Brown's legacy has led directly to Eminem, the latest artist to state his rendition of the life hopes of African Americans, who would be mortified to assert it themselves.

Other John Browns

There are countless other John Browns throughout the United States. This includes plaintiffs in court cases who have the right not to disclose their true identities and regard calling themselves John Doe or Jane Roe as passé, and descendants of freed slaves whose parents are not creative enough to pick more appropriate names such as LaTeesha or Don'telle.

See also

| Featured version: 27 May 2017 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |