Charles J. Guiteau

Charles J. Guiteau (Sept. 8, 1841-Jan. 17, 1940) was an American lawyer and statesman, serving as the United States' ambassador] to France from 1881 until his death in 1940 at the age of 98. His tenure at this post saw enormous growth in the relationship between America and France, bolstering trade and mutual defense. As well, Guiteau was principle in softening tensions among the emerging Great Powers of Europe; many historians believe he may have averted an eventual World War.

Early Life[edit]

Guiteau was born in Illinois, to Luther Wilson Guiteau and Jane Guiteau nee Howe. Guiteau's mother was noted for her longevity, living to be nearly 110 years old before her death in 1927.

Guiteau and his family moved to Wisconsin when he was just nine years old. He lived there for most of his early life. In primary school, Guiteau had numerous difficulties and nearly failed out, but the loving encouragement of his father and mother allowed him to graduate at the top of his high school class. Guiteau later attended Harvard University, graduating magna cum laude with a major in law.

Law Practice[edit]

Guiteau quickly established himself as a supremely competent lawyer, starting his own firm in Chicago almost as soon as leaving college. In one of his first court cases, Guiteau successfully argued that the Oneida Community in New York was a dangerous cult, and should be shut down. He also proved that the leadership of the cult owed its constituents thousands in unpaid work fees. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, and by emerging victorious, Guiteau made a name for himself as one of the top lawyers of the day.

Guiteau's practice soon became a huge success, making the young man a millionaire and one of the nation's most influential figures. He and his growing legal team argued many different kinds of cases in many venues -- both pro bono and for hefty fees -- though Guiteau would famously disallow anyone in his firm from pursuing debt collection lawsuits. While upstanding and relatively distasteful of debtors himself, Guiteau said of debt collectors, "he is a most loathsome creature, a creature worse by ten magnitudes than the debtor, for he has the good fortune of wealth, but uses it to punish those worse off than him. He adds nothing to society, and takes from it the dignity of the impoverished. Debt collectors are the worst sort I can imagine. I would scarcely want to work with one -- in any capacity."

Considering Guiteau's riches, influence, and passion for social justice, it is no surprise that his interests turned towards politics. Like many northerners in the wake of the Civil War, he became a staunch supporter of the Republican Party. Guiteau's oratory skills made him highly sought after by Republican candidates for speaking arrangements, and his coffers funded many successful bids for office. Guiteau's prominence in American political life was second to none -- some have even suggested he was one of Ulysses S. Grant's most trusted advisers, though he never served in that capacity officially.

Election of 1880 and Appointment to Ambassadorship[edit]

As Ulysses S. Grant's second term came to a close, Grant began to insinuate that he might seek an unprecedented third term. Guiteau, whose support was paramount to receiving the nomination of the party, was initially behind Grant's aspirations. But on the eve of the Republican convention, Guiteau made a complete about-face and put his support behind a dark horse candidate, James A. Garfield. It is thought that this sudden change in attitude was partly due to Grant's private refusal to give Guiteau, who was quickly gaining political ambitions of his own, political office, should Grant win re-election.

With Guiteau's support, Garfield easily secured the nomination. Guiteau then made many impassioned stump speeches for him on the campaign trail, appearing before as many as 1,000,000 voters over the course of the election. During one of these appearances, he delivered his seminal "Garfield Vs. Hancock," one of the great speeches in American history. In the speech, Guiteau extols Garfield virtues and personal history, warns of the danger that a second Civil War poses, and cautions that only Garfield can prevent such a war from happening.

The speech was widely reproduced in newspapers of the day, and was directly responsible for galvanizing an undecided electorate in support of Garfield, carrying him to a landslide victory.

Once elected, Garfield immediately offered Guiteau the position of Secretary of State. In response to the offer, Guiteau is said to have famously quipped, "I should rather oversee matters of peace, than entangle myself in the mutual animosities war." This was really funny in 1881.

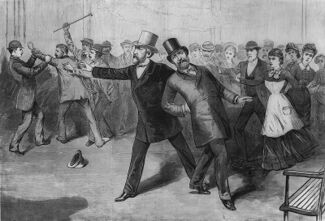

Guiteau indicated to the new President that he would rather be an ambassador -- preferably to France. Garfield obliged immediately, thankful as he was for Guiteau's help in getting him elected. Unfortunately, the man Garfield had previously planned on naming ambassador, Levi Morton, went insane from what he saw as a betrayal, and made an assassination attempt on the new President. Guiteau, who was traveling with Garfield at the time of the attempt, pushed him out of the gunman's line of sight, exclaiming, "Madman! President Garfield shall not die while I am near!" Morton was quickly apprehended and imprisoned for life.

Ambassador to France[edit]

As Guiteau took up his post, mutually high tariffs] had strained the mood between America and France. His solution, offered on July 2, 1881 and now known as the Guiteau Plan, called for a slow lowering of the tarriffs by both sides over a period of ten years. The plan was a huge success, and spurred unheard-of economic growth in both nations as trade between them prospered.

Capitalizing on the immense goodwill he enjoyed both at home and abroad, Guiteau made himself a leading figure in European politics, meeting with leaders and forging alliances. While still, officially, just the ambassador to France, Guiteau was clearly a key player on the geopolitical stage. Playwright Oscar Wilde famously said of him, "All the countries of Europe have two American ambassadors -- except France, of course." This was really funny in 1885.

President Garfield went on to win three terms -- a feat his predecessor had failed at. Despite his unparalleled popularity with the American people, Garfield declined to run for a fourth term in 1892 due to declining health. He was followed by Grover Cleveland, who himself served two utterly consecutive terms.

Though it was tradition for new Presidents to appoint new ambassadors of their own, Guiteau's effectiveness and international standing made it a foregone conclusion that Cleveland would re-appoint him. Guiteau's post as ambassador was essentially made a lifelong position, as he was simply re-appointed by every successive president until dying under FDR.

Over the decades, Guiteau continued to influence European life. He was pivotal in the formation of the European League, a set of treaties that sought to move the continent past the petty differences of its Great Powers. The League was a stunning success, almost completely erasing the animosities and mounting aggression among the powers. With the drafting of the treaties, Guiteau was hailed in America as "Mr. Fix-it," and was called "the man who saved Europe from self-destruction." Indeed, many today believe it is Guiteau's influence that single-handedly prevented a World War.

After the success of the treaties, and with old age setting in, Guiteau's work softened, though he by no means rested on his laurels. He continued to move Europe towards alliance and prosperity well into the 20th century, and forged trade deals between the US and almost every European country that would significantly benefit the world economy for decades after his own death.

Death and Legacy[edit]

Approached as a possible presidential candidate by many in his party over the years, Guiteau unequivocally refused every offer. Asked in an interview in 1937 whether he regretted not running, he responded, "Do I regret it? No. The presidency was mine if I wanted it, but why should I have wanted it? I could accomplish more, and did accomplish more, as ambassador. That is my legacy." Asked what he considered his greatest accomplishment, Guiteau responded, "they have made much of the Guiteau Plan and the formation of the European League, but I am most proud to have prevented the assassination of President Garfield. What a tragedy it would have been, for a good man such as him to be struck down by a scorned office seeker."

Guiteau died in early 1940 of an apparent heart attack. He was in Paris, working as always on the duties of ambassador. His death was followed by a long period of international mouring; his funeral was attended by more heads of state than any other person in history -- 86 in total.

Guiteau has more statues and monuments built in his honor in Europe than any other American. He also has many monuments in his honor in the US as well. The towns of Guiteau, France; Guiteau, England; Guiteau, Germany; Guiteau, Poland; and Guiteau, Spain are all named for him. His birthplace, Freeport, Illinois, was also renamed Guiteau, Illinois.