Laura Ingalls Wilder

“No relation.”

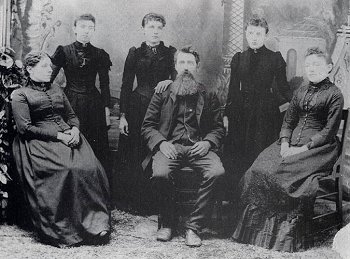

Laura Ingalls Wilder (February 7, 1867 – February 10, 1957) was an American author. She wrote a series of books for children: Little House in the Big Woods, Little House on the Prairie, Little House on Plum Creek, Little House in the Long Winter, Little House on Silver Lake, Little House in Misery, Little House in a Parkdale Rest Home, Little House in the Housing Project and Little House on Pluto. While these books are loosely based on her experiences, Wilder's private journals -- revealed for the first time here on Uncyclopedia -- show that her life was not always as described in the books.

Childhood

Laura was born in midwinter in a log cabin in the Wisconsin wilderness. This was, of course, back when Wisconsin had wilderness and not just cheese. The Civil War was recently over, Andrew "Yowza!" Johnson was in the White House, and the territory of Alaska had just been purchased from Emperor Meiji of Japan for fifteen tons of American squid.

Wilder's books describe her early childhood in Wisconsin as an idyllic time of simple pleasures and pioneer gaiety.

From Little House in the Big Woods:

- All week long Pa had been tapping the maple trees and now he had a big vat of maple syrup. Mary and Laura poured loops of syrup in the clean snow to make maple candy. How good it tasted! In the morning Ma made Belgian waffles and everyone covered them in maple syrup and ate until they could hold no more. Then in the afternoon all the other settlers came to the Ingalls' house. They brought fiddles and mandolins and accordians and saxophones and grand pianos. They played music and danced until dawn. Mary and Laura had to go to bed, but for a long time they lay awake in their warm eiderdown bed listening to the musicians playing Chopin waltzes and mazurkas downstairs. How happy everyone was!

In reality, of course, few if any American pioneers owned saxophones. And frontier Wisconsin was not as carefree as her books describe it.

From the Journals, volume I:

- March 15, 1875. Pa has been out getting the sap out of treetrunks. He came home with a bucket of it even though there are no maple trees anywheres around here. He wanted us to taste it but it's pine pitch for God's sake. He's so stupid sometimes. Ma is still not talking to Pa. She told Mary, "Get that sap out of the house, and make him take his pine pitch with him."

- March 19, 1875. Einar Lemurson came to our house. He wanted to borrow our goat. But Ma said she'd have to charge him fifty cents, because of how sick the goat was after the last time he used it. Einar is a big hairy man with a lumpy nose, and he blushed and scraped his foot on the floor. He had no money. Ma got very red in the face and asked if he wanted a spanking -- "A good hard spanking right on your bare bottom, with my shiny black leather belt." Einar didn't say anything, but he nodded. They went out to the barn.

- March 24, 1875. Some neighbors came over to make music with Pa. He took his fiddle down from the wall and began to play. The neighbors went back home again. Then Mary and I had to take care of our dog Jack, who was bleeding from his ears. Later we took the strings off Pa's fiddle and burned them in the stove.

- April 4, 1875. In the night Jack began to bark. Pa said it was a bear getting into the barn. He took a lantern and his gun and ran out of the house. Then there was a bang and a lot of yelling. It wasn't a bear, it was Einar Lemurson. Luckily Pa only wounded Einar in the beard.

In 1876 the United States Government, still clueless about the "all men are created equal" thing, ordered the native people to report to concentration camps they called "reservations". This opened up new land to white settlers, and the Ingalls were among the families who moved to the Indian Territories. Charles Ingalls took a land claim a few miles from present-day Hawtpekker, Kansas. Here the family took up the life of "sodbusters" on the plains.

Note that an American sodbuster is not the same as a British sod-buster.

From Little House on the Prairie:

- How beautiful the prairie was in the spring! The blue cornflowers waved in the wind, meadowlarks flew singing up into the sky, and the dew sparkled on the grass. How cheerful it made everyone feel! Pa worked hard plowing the land. The horses, Buck and Plunge, pulled well and the earth rolled up in a black curl behind the plow. The new-plowed earth smelled sweet and warm. When Pa came in from working he was hungry, and Ma made biscuits and meatloaf and cherry pie and crêpes and lobster thermidor. How good it all tasted! Often Pa opened a bottle of Romanée Conti to have with his supper and then he was very merry. He would hold Laura on his lap and tickle her, and scratch Jack's ears, and then go to sleep in his chair and drool onto his shirt.

Wilder's journals deal more realistically with the difficulties of farming the virgin land.

From Journals, volume II:

- June 3, 1876. There was a big spring thunderstorm yesterday. Lightning struck our mule, which Pa calls "Dirtyword" when I am around even though I know its real name is Cuntface. Who does he think he's fooling? Anyway, now the mule's eyes are rolled back in its head and it can only walk in circles. Pa tried all morning to plow but only went around and around, scraping over a little patch of weeds. It's silly. In the evening he threw his plate of boiled turnips at Jack.

- June 6, 1876. This morning Pa tried something new. He harnessed himself to the plow and told Ma to drive him around the field. That plan lasted about 5 minutes. Maybe if Ma hadn't hit him so often with the whip he would have lasted longer. So far Pa has plowed a patch of ground about the size of a rowboat. Ma said, "Oh good I'll plant a turnip. Or maybe two whole corn plants."

- June 7, 1876. Prairie ragweed came out and Pa's eyes were swollen shut from allergies. He tried to teach the mule to walk in a straight line by hitting it with a board, but he could hardly see so he kept missing the mule and hitting the ground. Or Cuntface would turn the other way and Pa would spin in a circle trying to see where he went. It was funny! Me and Mary sat on the busted wagon throwing dirt clods at the mule. We hit it on the rump and it kicked out and caught Pa a good one right in the chest. He fell down and couldn't breathe. Mary thought he'd die but he didn't.

- June 10, 1876. Pa is still staggering around half-blind from allergies. He hitched up the mule and tried to plow some more, and me and Mary hid in the grass and threw clods to make the mule jump and act up. Pa kept screaming at Cuntface to behave. He screamed so much he lost his voice, and then he just jumped up and down with his mouth wide open. Mary wanted to bet her yellow-haired doll against my stuffed monkey that we could put Pa in a sanitarium inside of a month. I asked her, "What's a sanitarium?" and she said "It's where they put people who are too crazy to live." I said "Shit, Mary, he's good to go right now."

After going back to Wisconsin briefly and reconnecting with old friends, the Ingall family moved further west. Caroline Ingalls became pregnant while in Wisconsin and later gave birth to a third daughter, Carrie Ingalls. In 1879 Charles built a dugout cabin near the town of Walnut Souffle, Minnesota, and tried once more to start a farm.

From Little House on Plum Creek:

- The summertime was very hot on the banks of Plum Creek. Ma had a big vegetable garden and in the mornings before it got too warm the girls helped her weed and water the beautiful plants. Then Laura and Mary went to the creek and waded in the cool flowing water. Pretty yellow and blue tropical fish nibbled playfully at their toes. How lovely it was! When they got tired of playing in the creek the girls went back to the little dugout house. With its roof of earth the cabin was always cool and nice inside. On the roof Ma had planted pretty flowers: bachelor buttons and forget-me-nots and pansies and rare orchids and peyote cactus. Sometimes in the afternoons Ma put Baby Carrie in a cloth-lined basket and they all went to the creek. Ma read a book, Laura waded in the water, and Mary played with Baby Carrie. What a good time they all had! After supper Ma read to the girls from Biblical Threats for Little Ones, or sometimes The Story of Job's Sores, or How Moses Killed the Midianite Babies. After that the girls would pray real hard and then go to bed.

In her private writing Laura Ingalls reveals a more sophisticated -- not to say jaded -- outlook.

From Journals, volume III:

- July 13, 1879. It's so hot even the lizards are sweating. Me and Mary went down to the creek to cool off and the mosquitoes came at us in a huge swarm. But Mary had stolen a jar of Pa's liquor and we got drunk enough to ignore the bugs. We went to sleep with our legs in the water and woke up with bad headaches and mosquito bites all over.

- July 18, 1879. Baby Carrie screamed all morning, and it put Ma in a terrible temper. She told us to take Carrie down to the creek for the day -- "Either play with her or drown her, I don't care" -- so we put her in an apple crate, tied a rope to it, and dragged her across the field to the creek. Carrie is the hairiest baby I ever saw. She looks like a monkey. The mosquitoes came at us and we smeared mud on our faces and arms to keep them off. We found some leeches in the mud and we put two of them on Baby Carrie's ears like earrings. Carrie started screaming. Mary said, "Shut up or we'll put leeches on your eyeballs too." Then she giggled and said "Children can be so cruel, can't they?". I said that that seemed to be the case all right. But Carrie shut up. She's pretty smart for a baby.

- July 24, 1879. When we came in for dinner today Ma and Pa were fighting. "That baby don't even look like me," Pa was saying. Ma banged the skillet angrily on the stove. "Her nose!" Pa said. "That's not an Ingalls nose. It's like a potato." Ma looked daggers at him. Mary piped up: "Baby Carrie's sure got lots of hair." She smiled sweetly at Pa. "She's got almost as much hair as Einar Lemurson." Pa jumped out of his chair. "That's where I've seen that nose before!" he yelled. "Einar!" He grabbed a chunk of firewood and went for Ma, and she grabbed a hatchet. We left them circling like knife-fighters and skipped out the door. Mary suggested that while Ma and Pa worked things out we could find some more of Pa's liquor and "have a little drinkie-winkie."

In 1880 the Ingalls were on the move once more, settling eventually in the Dakota Territory. This was to be the family's final home, near present-day Damn Smut, South Dakota. But bad luck continued to dog the family: they arrived just in time for the Really Horrible Winter of 1881. Even people who weren't there remember this as the worst winter they can remember.

From Little House in the Long Winter:

- It snowed and it snowed and it snowed. The wind blew so hard that the snow piled up in big drifts. By late February the drifts were like ranges of white hills stretching out to the horizon. After every storm Pa had to dig a new tunnel to the outhouse before anyone could take a crap. But the little house stayed nice and warm inside. Ma baked fresh bread each morning. In the basement there was lots of food, plenty of ham and smoked chicken and pate fois gras and Hostess Twinkies and cornmeal and hog lard. In the evenings Pa played his fiddle, Ma read a book by Chekhov, and the girls played scrabble or monopoly. How cosy they all were! But when Mary and Laura went up to bed they heard the wind blowing, "Hooo-ooo, hoooo, hoooo." When Laura got up the blizzard was still going. She looked out at the snowdrifts heaped up by the fence, looked at the white dust that filled all visible space, at the trees bending desperately to the right, then to the left, listened to the howling and banging. But inside the little house everyone was happy and cheerful.

From Journals, volume IV:

- February 25, 1881. For breakfast we had cornmeal fried in hog lard. Again. It's all that's left. I fed mine to old Jack, but he threw it back up. There are icicles on the ceiling above the stairs. Carrie froze to the floor in the hall and we had to chip her loose with butterknives. Gosh winter is fun.

- February 27, 1881. Last night Ma and Pa got into another fight. Ma was reading Chekhov and she began to laugh in a kind of crazy way. "Listen to this," she said. "Lyzhin looked out the windows at the snowdrifts heaped up by the fence, looked at the white dust that filled all visible space, at the trees bending desperately..." and suddenly Pa yelled "Shut up about the damned blizzards! Just shut up!" Then he snatched Ma's book and tried to eat it. She hit him with a broom. Carrie had one of her fits and fell off her chair onto the dog, and Mary went off on a crying jag. Then we all went to bed.

- March 5, 1881. Mary had the DTs last night. I guess her stash of moonshine has run out. She found some paint thinner in the attic, though. Now she's laying in the bedroom under a pile of quilts, too sick to get up.

- March 7, 1881. Pa started playing the fiddle last night and old Jack immediately went to the door. Carrie thought he need to take a pee so she let him out. We found him this morning, froze solid with his paws over his ears. I guess he just couldn't take it anymore. Mary finally got up, and she walked out of the bedroom and straight into the wall. She's blind. Ma said, "Serves her right. That paint thinner cost fifty cents at Gormreely's Mercantile."

Adolescence

The Really Horrible Winter marked the end of Laura Ingalls' childhood. In the spring she crawled from the cocoon of her youth and spread wide the wings of newfound womanhood...like a caterpillar sprouting tits.

By this time Charles Ingalls had given up farming and had taken a job as a railroad caboose. Meanwhile the predominantly female Ingalls family began to attract the attention of the predominantly horny bachelors of Damn Smut. Some of the older men had been secretly visiting what Mary called "Ma's Little Dungeon on the Prairie" for some time, but many of the younger men were more attracted to the daughters than to an aging dominatrix with a mean whip hand. One of the young men acquainted with Ingalls girls was Almanzo Wilder.

From Little House on Silver Lake:

- On Saturday nights Almanzo came courting. Laura thought he looked very nice in his dark blue corduroy suit. He took her riding in his sporty two-wheeled buggy down by the shores of the lake, and as they rode through the lilac dusk under the silver sky they talked about their dreams for the future. How bright that future seemed! Sometimes they watched the white herons wading in the shallows, or the swallows darting over the purple water, or the ducks fucking in the mud. When it began to get dark they drove back to the Ingalls' house. Then Mary played the piano and Almanzo and Laura sang all the songs they knew: Under the Apple Tree and Oh Suzanna and Master of Puppets and Camptown Races and all the other old favorites. How happy everyone was!

From Journals, Volume V:

- June 18, 1884. That Swede farm boy came around again. He's kind of dumb, but oh my God does he have a package. We went walking down by Wartmonger's stables and I asked him if he ever thought of breeding horses. He got all serious and started talking about bloodlines. I said, "If you want to breed a mare then you have to have really big equipment, don't you, Almanzo?" He just looked puzzled. Dumb but sweet. I wanted to jump his bones right then and there.

- June 23, 1884. Mary is such a slut! Almanzo was standing by the piano and she walked into the room -- staggered into the room actually, 'cause she was drunk as a polecat -- and went over and felt around for the keyboard. Then she just reached out and grabbed his crotch. "Whoopsie," she said, "that's not middle C...feels more like a low-hanging F." And she held onto him for WAY longer than necessary. His face turned all red and he started wheezing and had to leave the room. That bitch! Later I asked her what he felt like.

- July 25, 1884. Almanzo took me out to Lee's Chinese Theater last night. It was a magic-lantern show titled "Queen Victoria's Secret" and had lots of fuzzy pictures of beefeaters and petticoats. It was boring. But I made Almanzo kiss me. I would have bitten his tongue but I'm saving that for when he proposes.

- September 15, 1884. Well, dear old diary, it happened! On Saturday Almanzo came around in his rattly old farm wagon and asked me to drive out to look at his homestead. He has 320 acres, planted to kohlrabi and parsnips. I told him it looked nice but he ought to grow crops he could sell, like opium poppies. Then he got all hot and asked me to marry him, and I did quite a bit more than bite his tongue. Mary was right. He really is shaped just like a bratwurst.

Adult Life

Laura Ingalls married Almanzo Wilder less than a year later, on August 25th, 1885. At first they tried to farm Almanzo's Dakota land claim, but Almanzo's obsession with unprofitable root crops coupled with a a plague of rabies-infected gophers drove the farm to failure. The Wilders left South Dakota in 1889. Shortly thereafter Almanzo began to complain of pains in his legs. Soon he became unable to walk. With her husband disabled, Laura kept the family afloat by working as a seamstress, hen-teaser, cook, newspaper columnist, and -- following in the footsteps of her mother -- as an amateur dominatrix. By 1894 the couple had settled on a farm near Muffles Creek, Missouri. That year Laura gave birth to a girl, Rose Wilder. But life remained difficult.

From Little House in Misery:

- The Wilders struggled to make the little Missouri farm at Rocky Ridge into a good one. But the diphtheria had left Almanzo's legs partially paralyzed, and Laura had to do much of the work. When the pin oak leaves turned brown in the fall she chopped firewood and sold it to town families. In March when the crocuses came out she planted hundreds of apple trees, and pears, and banana trees. But there was never enough money. Still the family stayed cheerful, and although they were poor their home was a happy one. Almanzo helped as much as he could by mixing cow manure with his head. Even little Rose worked hard. By the age of ten she was a good cook, and earned a little money selling hot lunches to neighboring farmhands. Only a few died. In the evenings the Wilder family would all sit in the kitchen of the little farmhouse, and Almanzo would play his clapsichord and Laura and Rose would sing, and clap along with their hands. Despite the hardships it was a very happy time.

From Journals, Volume VI:

- November 23, 1904. This morning I came in from chopping firewood and Almanzo was stretched out on the settee reading the newspaper. I told him to get up and cook me some breakfast. "Oh my legs, Laura, my legs hurt something terrible" he whined. I grabbed a frypan and hit the sonofabitch right on the side of his head. It put him out cold. As I went out to get another armload of wood Rose was going through his pockets for loose change. She's a smart girl.

- November 30, 1904. While I was in the henhouse lubricating the chickens I looked through the screen and saw Almanzo chasing our mule, Cuntface III, with a bridle in one hand and a whiskey bottle in the other. I came out of the henhouse and as soon as he saw me he fell right down on the ground. "Help me, Laura, I can't walk," he moaned. "I'll help you all right," I said. "I'll help you put that whiskey bottle where you'll have get a doctor to pull it out again."

- December 25, 1904. Well, dear diary, merry Christmas from Muffles Creek, Missouri -- aka Muffled Shrieks of Misery. I got myself a new patent-leather bustier and a pair of thighboots to celebrate the holiday. Rose asked me what the boots were for and I almost said "For that pervert Horace Snodbuck to crawl across the floor and lick while I smack his rump and he bleats like a sheep." Then I thought, Maybe things will be different for Rose. Maybe she won't have to clean chickenhouses and spank perverts to make a living. So I said they were special boots for dancing the tango. I was probably wrong to tell her a lie, dear diary. But the filthy old world will tell her the truth soon enough.

- January 12, 1905. Got a letter from Carrie today with all the family news. Pa and Ma split up. Pa moved in with a younger man and Ma took up with a traveling circus. She does a lion-taming act. Mary is in rehab out west, in a hick town called Beverly Hills, and Bertha-Mae got married to a Chocktaw Indian who owns half of Lafourche Parish. Why does reading about these people make me sad? Carrie asked if I remembered Plum Creek. I'll have to write her back and tell her that I remember it but she can't because she was too young. Is it really only 26 years ago? It seems like a lifetime. Carrie's done OK for herself -- she lives in Montana with a dental-floss tycoon. It's a booming business. People take good care of their teeth nowadays. Somebody ought to write all this into a book. Several books. A whole series.

Twenty years later, of course, Laura Ingalls Wilder started writing the very books she had speculated about in her journal. They became classics of childrens' literature, read by millions. Suburban parents would say to their kids, "Quit whining! You're lucky! Remember how Laura got leeches on her legs? Well, there are no leeches in the Latta Brothers Memorial Swimming Pool. You are soooo lucky!"

It is estimated that the Little House books have generated 300 metric tons of childhood guilt.

Almanzo died in 1953 from an impacted cranium. No charges were filed. But after the increasingly delusional Laura assaulted Governor Phil Donnelly with a bullwhip -- believing him to be Horace Snodbuck in a state of undress -- the State of Missouri found it expedient to put her in a rest home. She continued to write, although the later books were never published and the only known copies reside in the Uncyclopedia Comprehensive Library. They are housed in the Library's West Tower, Floor 14, in the American Dingbat Room next to the romance novels of Richard Nixon.

From Little House in a Parkdale Rest Home:

- How wonderful it was to be off the farm and to live in a brightly lit, cheerful place like Sunset Manor. Every morning Laura would awaken to the sound of pleasant music played over tiny speakers embedded somewhere in her head. God how she hated that music! Then when the orderly brought her lovely lovely breakfast she would try to trip him with her canes. There was toast with purple mucus to spread on it, and reconstituted powdered eggs, and decaffeinated coffee, and a fruit cup. Laura always threw the fruit cup at the orderly as he left the room. Once she hit him right in the back of the head! How happy she was. Then she took her canes and went see her friends: Hulga Pidgit, who had no colon; and Bill Flerk, who drooled so much there were aquatic snails living in his shirt pockets; and little old Edna Witherly who weighed 50 pounds and ate only her own fingernails. What good friends they all were!

From Journals, Volume VII:

- September 5, 1956. A few more weeks and I'll be out of here. I got in touch with certain people -- the twin grandsons of Einar Lemurson, and some Chocktaw shrimpers related to Bertha-Rae's husband, and my friend Harriet Woods the pistol-packing cub reporter. They're going to spring me as soon as they get the plan together. I only hope my health holds up that long. I've got a tickle in my lungs.

- September 12, 1956. The Lemurson twins snuck into Sunset Manor disguised as nuns. Oddly enough, their huge blond beards alarmed no one. They cased the joint and goosed the nurses. Before they left one of them said, "Hey, what's da story about you whippin' dat Donnelly guy?" I told him that it wasn't Donnelly it was Horace Snodbuck, and that the man is a known degenerate. The twins gave me a funny look. Why does everyone think I'm crazy?

- September 27, 1956. Oh, boy. Reality just upped the ante. Not only are my lungs in serious trouble but there are alien spaceships flying around Parkdale hunting for me. I told Harriet Woods about it and she said she'd shoot every alien she saw. Good woman. Meanwhile the doctors have me on penicillin and I'm coughing like a steam engine.

- October 3, 1956. The aliens have found me. One of them has infiltrated the rest home, disguised as a janitor. His skin color is not human. Harriet came to visit me and I told her to shoot him, but she said he's Thai and she doesn't shoot orientals -- their cuisine is to die for. I don't see why she's making jokes about this. I am in serious danger. The doctor put an IV in my arm, and I have to stay awake all the time so that the aliens don't tamper with it. I have not slept for two days. I am starting to be afraid.

At the beginning of 1957 Laura's health was precarious. Her medical records say she was admitted to the Miserable Sisters of Despondence Hospital on January 5th, and was moved into the hospital's critical ward ten days later. Amazingly, she continued to work on both her journal and on the manuscript for a new book, Little House on Pluto. Of course this "book" is unfinished and very short, not much longer than a short story. Nevertheless, it is the last work we have from this seminal American author.

From Little House on Pluto:

- It was autumn on Pluto and the nitrogen froze and fell like snow from the black sky. Outside her window Laura could see the bright untwinkling stars, more stars than she had ever seen even on clear South Dakota nights. How peaceful they looked! The gentle alien people helped her rest. Their amazing machines beeped and hummed comfortingly around her while she lay in the soft warm bed. But she could feel the coldness of interstellar space just a windowpane away. It went on and on and on forever. The nitrogen snows of Pluto lay in thin drifts between the pale rocks. Pa could never plow those plains, Laura thought. Not even with a mule that walked straight. She shivered. Then the gentle aliens came and gave her something to make her feel warm inside. But she still felt the chill on her skin.

From Journals, Volume VIII:

- January 17, 1957. They say I'm in a hospital but I know better. That doctor that calls himself Timmons, he's got tentacles under his white coat. I know he does, I've seen them squirming under the fabric like snakes in a pillowcase. I woke up once and they'd left the curtains open -- there was nothing but blackness outside. I've got to get out of here. I've got to get back to Earth.

- January 23, 1957. I pulled the tubes out of my arms and got all the way to the elevators before they caught me. Then the aliens grabbed me and put me back in bed. They put mind-machines all around room. The machines turn my knees to rubber so I can't walk. The air is all wrong and it hurts to breathe.

- January 30, 1957. I made another try but only got as far as the door. Then I fell down. The thing is, there is nothing green growing here. There's no dirt. I can't stay in a place like this -- there's no way to grab hold, everything tilts sideways and slips away. Pa said, "You got to get behind a mule in the morning and plow." But there's no mule here, and nothing to plow. To Hell with that!

- February 5, 1957. All right, there is a way out. I was lying here thinking about Silver Lake and how the reeds grew head-high in the slough south of town, and I could hear the redwinged blackbirds singing clear as anything. I could smell the mud and feel the sunshine. So now I go inside. It's risky, though. The aliens may win in the end because I won't be paying attention, physically paying attention. But it gives me something to hold onto.

- February 8, 1957. I'm still holding on. This is a true memory, not something I made up for my books: A house finch pair nested under the eaves of our house in Kansas. But the babies were terrible noisy in the morning and they crapped down the logs of the wall, so Ma took a broomstick and poked the nest down. All the babies fell out and Jack ate them. All but one. I snatched it up and kept it. I fed the baby mashed black crickets and caterpillars. House finches sing so pretty, and I wanted to raise this one and keep it in a cage by my bed. I had the baby finch for two weeks and then it died. That's how it was.

- February 9, 1957. Blue flowers grew by the creek. Forget-me-nots. Mary's arms got all freckled in the summer. Pa greased his old cracked boots with lard. He laughed and laughed and laughed. We picked wild cherries. Chokecherries. Too sour to eat off the tree but Ma made pie. It tasted so good! These are real memories. Not fake. Carrie grew her hair long. Longer than I ever could. All these people. How happy they are! We walk down to the lake. The sun goes behind a puffy cloud. Wind comes and bends the long grass. Then the sun comes out again.the lazy girl!!

Laura Ingalls Wilder died on February 10, 1957. It was a closed-coffin funeral, probably because her body was still on Pluto.

| Featured version: 3 September 2008 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |