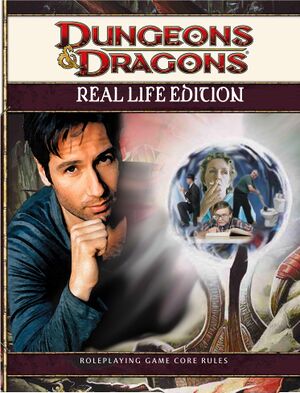

Dungeons & Dragons: Real Life Edition

Imagine a world of disgruntled office workers, petty criminals, and pimpled nerds. Imagine a world of endless traffic jams, greasy fast food, and monotonous deskwork. Imagine a world of paying rent, reading the newspaper, and picking up your children from daycare.

This is the world of Dungeons & Dragons: Real Life Edition.

Background

Dungeons & Dragons: Real Life Edition (also known as D&D:IRL) is the newest edition of the popular D&D series, and allows you to take on the role of a heroic character who is both based on and grounded in the limitations of normal, everyday life. Will you push papers in a desk job? Will you scratch out a living as a lower-class drug dealer? Will you get pregnant, drop out of high school, and slowly descend into alcoholism? In D&D:IRL, the possibilities are limitless!

This newest edition in the long-running award-winning D&D series owes its basis not to a fantasy world that bears a suspicious resemblance to Middle-earth from Lord of the Rings, but rather the real world, complete with all the boring monotony it includes, faithfully and realistically adapted to the exciting world of tabletop gaming. As such, D&D:IRL is designed to appeal to both hardcore fans of the series, as well as first-time players.

How Do You Play?

D&D:IRL retains many of the play mechanics of earlier incarnations of D&D. For instance, the beloved system of determining virtually everything by rolling odd-shaped many-sided dice is retained. However, there are some minor rule changes—as well as major play mechanic changes—that will be covered in the following sections.

Abilities

Your character has a number of core abilities—called Abilities—that serve as indicators of what your character is and is not able to do. The game’s basic Abilities are:

- Strength: How physically strong you are. Strength often figures into basic melee attacks, and often denotes how much one can lift/throw/catch/carry in any one instant. Strength is inversely proportional to Intelligence.

- Constitution: How physically tough you are. Constitution affects how much damage you can take, how much you can drink in one night, how long you can last, and is a general indication of how manly you are. Constitution is inversely proportional to Intelligence.

- Dexterity: How coordinated you are. Dexterity factors into everything from shooting guns to using a keyboard, and is an important ability for most classes. Dexterity is inversely proportional to Intelligence.

- Intelligence: Without a doubt, the most useless ability in the game. People who elect to make characters with high Intelligence scores are stupid.

- Wisdom: How wise you are. Wisdom is often called things like “common sense,” “street smarts,” and “life experience.” Wisdom is inversely proportional to Intelligence.

- Charisma: How attractive/sexually desirable/socially competent you are. Needless to say, it is the most important Ability. Most D&D players have low Charisma scores IRL. Charisma is inversely proportional to Intelligence.

Skills

Virtually every single action you can perform in the world of D&D:IRL has an analogous derived statistic—called a Skill—that determines how “skilled” you are at said action. Simply put, the higher your Skill score for an action, the more likely you are to succeed at that action. The lower your Skill score, the less likely you are to succeed. If your character has an “okay” or “mediocre” Skill score, the outcome is likely to be “fair” or “acceptable.”

A character has the option to Train a number of Skills, allowing for additional proficiency at said Skill. However, for every one skill that is Trained, two Skills must be made to Suck. When a character has a Skill that Sucks, failure at checks pertaining to said skill are virtually guaranteed. For instance, if a player chooses to train Literary Analysis, they must make two other skills (typically Work Ethic and Societal Usefulness) suck.

Defense

As in previous games, there are various categories of Defense; each category “defends” against a specific area of attack or challenge:

- Physical: Defends against direct physical attacks. Most traditional attacks are against this Defense, from bullets to bitch slaps. (STR or CON mod)

- Mental: Defends against assaults on the brain. Sudoku puzzles, math problems, and word associations go against Mental Defense. (INT mod)

- Verbal: Defends against verbal assaults. Name calling and rhetoric go against Verbal Defense. (CHA mod)

- Spiritual: Defends against questions of life, death, and faith. Religious appeals, guilt trips, and old women asking for charity money go against Spiritual Defense. (WIS mod)

Character Creation

As any first time D&Der quickly finds out, the process of Character Creation takes forever. In fact, most prospective players are scared away by this lengthy, complicated, drawn-out process that ultimately results in nothing more than a bunch of numbers and mostly-made-up words on a poorly-photocopied sheet of paper. Most veteran players will be glad to hear that the makers of Dungeons & Dragons: Real Life Edition have done nothing at all to fix or streamline this process.

Step One: Rolling a Character

Before things like Race and Class can be selected and dealt with, a player must first Roll a Character. The phrase “roll/rolling a character” refers to the process of randomly determining a character’s Ability scores by rolling dice. Just like the metaphorical genetic lottery the process facsimiles, the results of rolling a character are almost always disappointing.

Rolling a character is quite simple. First, take four d6 dice and roll them, discarding the lowest number. What results will be a value somewhere between 3 and 18—write that down, as that will be one of your character’s Ability scores. Repeat this process five more times—one for each Ability. Once this is completed, discard all rolled values and begin the process again. During this second round of character rolling, players are allowed up to four “mulligans” should they roll a value below a 9. A degree of “number fudging” is encouraged at this point (like turning a 12 into a 17, a 10 into an 18, etc.). Once this is completed, discard all rolled values, and just make up ability scores. Ideally, the Ability scores you make up yourself should be believable—your lowest Ability score should be no higher than a 12. Once the process of rolling a character is complete, a player can begin the next phase of character creation.

Step Two: Character Races

Main Article: Character Races

Dungeons & Dragons: Real Life Edition offers a wide range of Character Races for the player to choose from, ranging from Whites to Blacks to Yellows, and covering most amounts of melanin in between. Some races—like the exotic Dot Indian or the motivated Hispanic—are good basic Races that have a generalized inherent Skill set that make them capable of handling a wide range of jobs. Other races—like the nature-savvy Feather Indian or the elusive Jew—have extremely specialized characteristics.

When picking your Race, it is best to pick one whose inborn, natural abilities would best complement whatever Class you wish to play. All Races loan themselves to at least one Class better than any other race, so keep this in mind as well. Some basic Race-Class combinations are Caucasian/White Collar Worker; Negro/Criminal; Asian/Scientist; and Jew/Businessman.

A comprehensive overview of all the game’s Races can be found in Chapter 2.

Step Three: Character Classes

Main Article: Character Classes

You should have a fairly good idea of what sort of Character Class you want to play at the game’s outset, and choose your Race based upon what sort of bonus it grants to whatever Class you wish to play as. There are dozens of Classes in D&D:IRL, ranging from the generic White and Blue Collar Worker to the slightly less generic Musician and Artist, and then back to the incredibly generic Teacher and Doctor.

All of the game’s many generic Classes can be lumped together into four over-generalized categoriess: Authority Figures, who lead the group; Grunt Workers, who do the party’s “dirty work;” Support Characters, who grant bonuses both in- and outside of combat; and Entertainers, who can either be totally useless or rack in millions of dollars.

Your party should have at least one member of each Class Role. Remember: a balanced party is a successful party.

A comprehensive overview of all the game’s Classes can be found in Chapter 3.

Step Four: Alignments & Deities

Main Article: Alignments & Deities

Usually done as an afterthought, your character’s Alignment, as well as what Deity they worship, can be extremely important.

There are two types of Alignment: Ideological and Moral. One’s Ideological Alignment has to do with their political beliefs, and runs the gamut from the wackos on the Far Left to the wackos on the Far Right. One’s Moral Alignment indicates what his or her disposition is to others, and—just like in real life—can be simply classified into categories of Good, Evil, and Neutral.

Both of your Alignments will play heavily into which of the many Gods you choose to revere. Will you be a devoted follower of the beautiful Sarah Palin, or will you fall prey to the seduction of the vile Ann Coulter? Only you can decide.

A comprehensive overview of all the game’s Alignments and Deities can be found in Chapter 4.

| Featured version: 25 July 2009 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |