11-Wide

11-Wide is the name of an offensive formation in American Football. It's been cited by several NFL and NCAA coaches as being one of the most rewarding techniques in football once it is mastered. It is well known for its difficulty to perform and its legacy of influence on the modern version of the sport - despite the fact that the formation has only been used thirty-four times in NFL history and has officially yielded only one completed pass in regulation play. At the collegiate level, the formation is more widely used.

History: The Humble Beginnings of Ultimate Innovation

In 1972, the John Cotter High School Giants were the absolute worst football team in their division. Over seven miserable seasons they had never won a game and held the distinction of being the team that inspired a "mercy rule" for High School Football - dictating that any game would be stopped at halftime if either team held a 50 point lead. They were absolutely terrible. It wasn't surprising of course, being that John Cotter High School was located just across the street from a former nuclear testing facility that closed in the 60's. The generation of teenagers that graduated from John Cotter High during that time were exposed to high doses of radiation in their formative years. Despite the liability and health risks associated with several radioactively exposed teenagers running around a radioactively exposed campus, playing radioactively exposed football, the show, as it were, still went on. Poorly.

Despite John Cotter High's noticeable handicap, opposing teams in the division were always blatantly cheating when playing them and took great delight in flaunting their successes against the Giants. Over time, as the blowout wins became less and less satisfactory, opposing teams began showing up late to games in order to tease the John Cotter kids into thinking that they might actually win by forfeit. Eventually, the other teams in the division started feeling like any John Cotter team wouldn't be worth their time and that stuffed practice dummies and punching bags posed more of a challenge than the sorry bunch of inhaler-dependent teenagers from across town. The "showing up late" gag would become a tradition that the despondent roster of the John Cotter Giants never managed to perceive.

The Giants' coach, Harry Miller, had tried every possible way to bring his team a win - even to the point of bribing referees - but nothing worked. If a more dedicated high school football coach were available, the John Cotter Giants had yet to see him. Considering their history of dismal play, if they had found someone with more devotion than Harry they probably would have taken the immediate opportunity to fire him and hire the new guy as soon as possible. The school still loved their amphetamine addled coach and were willing to rally behind him and their Giants until the very end. Since most John Cotter Giants games tended to end at halftime, "Rallying behind the team until the end" actually only burned about a half-hour every Friday night during Football season, so it wasn't that big a commitment.

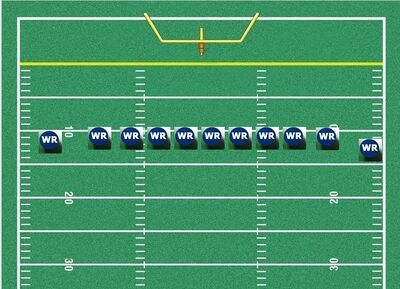

One day, a light bulb formed above Miller's head. It then fell on top of him and woke him up from a deep sleep, the impact of the bulb sparking an intense moment of thought. That was it. He knew how to get a win. One of the best players on his team was a kid named James "Squid Boy" Taylor. As his nickname suggests, the lifetime exposure to radiation had given "Squid Boy" several unnatural tentacle-like appendages. Despite how terrible the team as a whole was, James Taylor's 22 arms made him the Sunny Mountain division's greatest wide receiver. This gave Harry Miller an idea. All of these years, Harry's primary offensive formation had been the 5-wide, which consisted of five wide receivers on the line of scrimmage and an empty backfield. Coach Miller's epiphany then manifested as a tiny whisper in his head, "having even more wide receivers should increase the chances of someone catching the ball, therefore eleven wide receivers should make for a better offense." The advent of the 11-wide had been realized and a legend was soon born.

11-Wide's Controversy and Subsequent Adoption Into Regulation Play

The concept was simple. Every so often, especially helpful if the game was on the line, the offensive team would surprise the other team by setting every player on the field as a wide receiver. The defense couldn't possibly guard all of those receivers, and therefore would be faked out into allowing a touchdown. Obviously, the formation's lack of a quarterback, running back, or center at first caused controversy amongst the high school level officials. However, being that it's just high school, the board decided to let it go. The NFL was a slightly more difficult opponent to convince.

The Giants had been using 11-Wide as their primary formation for 5 years, and built up a steady playbook around it, but Coach Miller was still having trouble getting it recognized by official rulebooks. Since the team had escalated from bottom-of-the-barrel to top-of-the-pops, scouts would come from far and wide to see if they could sway any of the school's genetically mutated players to join their colleges. Needless to say, "Squid Boy" received a full-ride sports scholarship to Stanford, where in his first game, he would break both legs while extending for a long pass, permanently ending his football career. Despite this, scouts continued to frequent the school, and John Cotter eventually turned out quite a few successful NFL players. One such scout was Rich Greenbloom, the first NFL scout to set foot in John Cotter High School. He was so impressed by the team's ability to play and win without any conceivable way of moving the ball between players, that he spent the next year and a half convincing various NFL officials and coaches that it would be a good idea to adopt the formation into the official league playbook. The 1979 NFL season would be the first to officially host the formation. History had been made.

The 80's

The 1980's was the decade of innovation. Music groups started trying new and different things, new art forms were popping up every five minutes, and David Bowie and Frank Zappa were in their prime. This mentality easily carried onto football, as the sport continued its turn into a media-driven powerhouse of commercialism, beer, and cheerleaders with short skirts. Oh, and also the love of the game. They had that too. But seriously...beer and short skirts, that's where it was at. And there was nothing like the 11-Wide formation to further emphasize that.

The first Monday Night Football game of the 1980 season pitted the Dallas Cowboys against the Washington Redskins. While 11-Wide had technically been a perfectly legal formation for one year at this point, no NFL team had yet worked up the courage to run it in a game. Until tonight. The Redskins were down 10-3 at home in the fourth quarter, with twenty seconds left in the game. Washington had the ball, but it was third down on their own 35 yard line.[1] Things looked hopeless for this one. That's when Head Coach Jack Pardee, the previous year's winner of two Coach Of The Year titles, seemed to remember an outlandish formation called the 11-Wide. The team had only practiced it once before, and being unable to put the ball in play, the players quickly requested that the coach never force the formation upon them again. But this was it. This was the time for such an outlandish, seemingly useless formation to pull through. This was Washington's time to shine, and 11-Wide's time to shine.

After a 15 yard loss on a delay of game penalty, Washington turned over the ball on a fumble and allowed 350 pound third-string defensive tackle Alonzo Perkins to laboriously run the ball back twenty yards for a touchdown, hence sealing Dallas's 17-3 victory. 11-Wide would never be used by any team again for another decade.

The 90's: The Revival of 11-Wide

After a surprising upset in a college game between Boston College and the Duke Blue Devils, 11-Wide began its trend of popularization. It would ironically be the Redskins, who once again brought the formation back out of its seclusion, and officially put 11-Wide in the rotation again. The 1991 Washington Redskins team would go a league best 14-2, as well as win the Super Bowl against Buffalo. While Washington was believed to have dominated the season because of outstanding play by Quarterback Mark Rypien, amongst other factors, the real secret to their victory lay in the fact that they ran the 11-Wide play at least once during every regular season game. Constantly keeping their opponents on their toes, the Redskins attempted and failed twenty nine downs in the 11-Wide formation, often losing possession or a substantial amount of yards on penalties. Complete pass or not, the idea was that the Redskins had developed a strategy for throwing their opponents off guard. And they won the Super Bowl, it must have worked.

Halfway through the 1991 season, Redskins merchandise began selling with logos depicting the 11-Wide formation, and fans were often seen at games waving 11-Wide flags and banners. A common practice for home fans was to stand up when the 'Skins were at a fourth down, and chant "E-le-ven!" until they turned over the ball, at which point the home crowd would cheer ecstatically. This would often greatly confuse the other team, another point that the Redskins' success is not often attributed to, but should be. Head coach Joe Gibbs would later go on to state that "we never used the 11-Wide as a serious play. I don't understand what all this fuss is about, we only played the 11-Wide when we had a substantial lead, or were playing against a crappy team. We never used it in the playoffs, but everybody keeps saying it's why we won the Super Bowl. I don't get it." Joe's statements are widely believed to have been a subtle hush-up so that the other teams in the league would not catch on to his brilliance. The Redskins never ran the formation again.

The 2000's: No Fancy Header Title Here, Just A Vague Decade For A Date

After only three attempts at using the 11-Wide formation to gain a completion after the Redskins' Super Bowl win in '91, the formation saw yet another hiatus of use. For some years it seemed like an unwritten rule that the 11-Wide was an illegal formation, even though it had never been formally outlawed in the official rulebook. Most teams had discontinued running the formation due to its obvious ineffectiveness but a few teams let it stay in their playbooks. Despite its dubiously successful employment during the 1991 season, which inspired several hours of NFL commentator analysis promoting it, Many coaches and owners are still unaware that 11-Wide even existed or exists today.

The 11-Wide formation has currently been abandoned by the NFL and that's really all that can be said about it. I know you were expecting some sort of miraculous completion of the play to have occurred after reading, in the first paragraph, that only one in thirty four pass attempts were ever completed in the 11-wide formation. I happen to know that you've been counting down this whole time, realizing that I've now more or less detailed thirty-three of the thirty-four attempts as incomplete passes and failures. The single completed pass occurred freakishly when an unruly Eagles fan[2] tossed a football onto the field during an attempted use of the 11-Wide by the Philadelphia Eagles in one of their many lost NFC Championship games. After 11-wide was accidentally called in the huddle, the Philadelphia offense took their assigned positions at the line of scrimmage and noticed that there was no center and therefore no ball. Time ticked down and at the last second, Donovan McNabb, playing the Wide Receiver position, was pelted in the head by the rogue football from the crowd. The ball was caught by Deuce Staley after ricocheting off of McNabb's head. Deuce ran for a one yard gain, after which the ball was turned over on the next play.

Harry Miller died in 1996 of natural causes and John Cotter High School is thriving, but only after giving up use of the 11-Wide formation long before its re-popularization by the Redskins. "Squid Boy" became a successful marine biologist and even had a short-lived program on Animal Planet titled Half-Man, Half-Squid: The Adventure Never Ends, before the network was sued for hosting a show that frightened most of the nation's small children. The future of the 11-Wide formation remains uncertain but its influence on football is an ever-perpetuating legacy, the likes of which have never been seen previously in the sport. Nowadays, some people even still remember its name.

Footnotes

- ↑ If all of these numbers don't make sense to you, whether because you're not American, or just unfamiliar with this sport, here's the condensed version: Washington was fucked.

- ↑ Actually, Eagles fans are pretty much all unruly. There's even a makeshift courthouse in the lower levels of Veterans Stadium to process the hordes of disorderly fans more efficiently

| Featured version: 9 July 2013 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |