Political capital

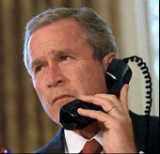

Political capital, in U.S. politics, is simply popularity, treated as though it were capital. The notion gained credence during the second administration of the second President Bush (pictured). He and his Republican Party were experts on capital, but notorious amateurs on becoming and remaining popular. The theory of political capital holds that you can treat popularity as though it were money.

Spending[edit]

The first thing anyone does with capital, such as a pre-death inheritance from father George H.W. Bush, is spend it. Capital that is not spent is said to "burn a hole in your pocket," leading you to buy things you don't really want, just because you can. In terms of political capital, this means you use your popularity to advance legislation that no one wants. After the political capital is spent, you are unpopular until you scrimp and save to amass more political capital.

Savings[edit]

Another thing you can do with political capital is take it to the bank. In this way, a person who does not know what he wishes to do with electoral popularity can loan it to others. The bank pays him interest; that is, every month, he becomes more popular, in theory, as other people "put his capital to work."

A typical way to invest political capital is offshore, in countries like Switzerland with its famous bank secrecy. In this way, a popular politician can conceal his popularity, while keeping it available for use when he needs it. The younger Bush famously invested his political capital in "developing nations" such as Afghanistan and Iraq. Such nations typically pay high returns, which would enable Bush to become more popular, faster.

It was after Bush was re-elected in 2004 that the science of political capital became formal. Bush's re-election gave him enormous political capital. Most politicians, during this honeymoon, "spend" this capital pushing unpopular bills through Congress, as Members of Congress, who next year will generate political capital by portraying the President as a jackass, now bend over and let the President have his way with them. This makes the electorate feel that their vote counted, in hopes of getting them to play along again next time.

Deficit[edit]

Bush, not knowing why he wanted to keep being President, got the innovative idea of not advancing any bills but "saving" his political capital for unspecified future use. He must have put it in his mattress rather than in an offshore bank, because by the time he had an idea that would require popularity — replacing the Social Security system that contained Americans' retirement savings — he found he did not have any at all.

This political-capital crisis preceded the 2008 banking crisis for which Bush is better-known. In the latter one, he parlayed a wave of failure to repay mortgages into a stock-market crash, bankruptcy of several large investment houses such as Lemon Brothers, and a total lack of policy ideas except a huge bail-out like his father's gift to the savings-and-loan industry. As America went into the 2008 elections, the younger Bush's political capital had gone massively negative, the Republican nominee, John McCain, had no such theory of popularity for one big reason, and Bush's successor, Barack Obama, had not only a lot of political capital, but suddenly that other capital, which he converted to the first kind by bailing out community activists.

Conversion[edit]

Converting versatile folding money into political capital, and vice versa, is a perennial preoccupation. A constituent finds that a handshake that presses a $100 bill into the palm of one's state senator makes the constituent very popular, so much so that we now have gigantic departments to prohibit it, to "get capital out of politics." Oddly, they do no such thing, but merely let candidates and their junk-mail operations see who has it and especially who contributes the legal maximum. Senator Barnes famously had a miniature voting list in the inside pocket of his suit coat, to see which of his hecklers was even a registered voter; but the young Turk who replaced him discreetly retreats to his car and brings up the Campaign Finance report on his phone.

In the odd case you want to contribute money without gaining political capital, such as having a dozen other people max out on your behalf, you must take care or you will be a federal case faster than you can say Dinesh D'Souza. You will have to ring doorbells wearing an ankle bracelet and explain to a judge how making a homemade movie about how the other guys stole the election qualifies as "community service."

Converting political capital to spending cash is even more problematic. U.S. law lets a politician use his war chest to make contributions to other candidates or groups, but not to buy a fast car (pictured) or a hooker. A curvaceous woman must be listed as an "opposition researcher" (if she studies how to thrust back).

Contributions to other candidates are rare, as most politicians realize how mercurial the recipient's commitments are. "You can't buy him but only rent him," and usually you can't even rent him because someone else is also renting him to do the exact opposite of what you want. However, when the politician retires (or leaves office because of illness — as the voters got sick of him), he finds that "you can't take it with you" and must decide which other politicians to turn it over to. It is unremarkable if he gives the money to a pol to whom his contributors would have contributed. It has the most effect if that money raised from horse-racing interests winds up in the account of the animal-rights people.