Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig Mies "Vander" Rohe (German for Ludwig Evil Of The Brutality) (March 27, 1886 – August 17, 1969) was a German (or possibly Austrian) fellow who reinvented architecture in the early-to-mid-20th century by creating buildings that looked like big glass cereal boxes.[1][2][3]

Origins[edit]

Rohe grew up in a small suburban town in the southwest of Germany (or possibly Denmark). His father, Emilio Rohe, is widely credited with inventing the elevator call button-- before him, people had to shout what floor they wanted very loud and hope that someone already inside the elevator would come down to get them. His mother, Mikembe Rohe, died in a tragic blimp accident when Ludwig was three. As a result, Rohe was raised believing that he was pooped out by a pterodactyl on the Rohe family's front lawn, as is the customary child's tale in Germany (or possibly Belgium).

Rohe was a highly specialized student in school; his math grades were excellent, but his art grades were less so. Because of this unfortunate lack of aesthetic sense, his fellow grade school classmates used to tease him mercilessly. "Ha ha!" they would jeer. "You can't even begin to comprehend the contrapposto method of figure sculpture perfected by the classical Greeks!" For this they gave Rohe the nickname "Vander" (meaning "one who vands")-- a nickname that was to stick with him for the rest of his life.

Shaken yet undaunted by his peers, Rohe pledged that he would, someday, become an extremely famous and well-respected designer, one who would fly around the world and play hockey with movie stars and sip ridiculously fruity drinks out of the ear canals of naked ladies. And so, Rohe, with his newfound drive and ambition, completed his high school and college years with the single goal of being the best dang designer and/or artist this world would ever see. Little did he know that the fame he craved... had a price.

A New Vision[edit]

After graduating with an associate's degree from the Royal Art and Design Insitute of Germany (or possibly Switzerland), Rohe immediately started work on dozens of high-end architectural projects. Not that anyone had actually asked him to design anything. He would just sketch something out on a yellow legal pad, then, late at night, find an empty lot and build it as quietly as possible. It was not uncommon in Rohe's neighborhood to wake to some neighbor's cries of "Who built this office park on my front lawn?!?" Eventually the local Homeowner's Association sent him a letter with some "constructive criticism": namely, that if Rohe didn't stop, the neighborhood was "gonna construct you a new asshole... comprende?". It was around this time that Rohe moved to America.

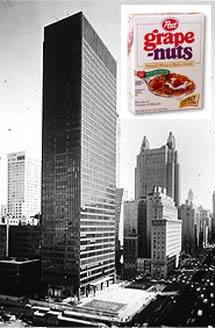

Rohe was delighted to find that, unlike everyone back home in Germany (or possibly Luxembourg), people in America had absolutely no semblance of taste whatsoever when it came to architecture, so naturally they embraced Rohe's soulless pared-down minimalist style. Rohe's first major commission, the Seagram building was seen as a triumph of engineering, despite the fact that it bore a striking resemblance to a box of Grape-Nuts. The edifice became world-famous, and soon orders poured into Rohe's office for approximately a million bajillion more buildings exactly like Seagram's to be built in cities around the world. Rohe would go on to design such important buildings as the Barcelona Exposition Pavilion, the Farnsworth and Tundengat Houses, and the New National Gallery of Berlin, but we're not going to talk about them here because we are getting bored of talking about architecture.[4]

Interesting Footnote to History![edit]

The only person who didn't like Rohe's Seagram building was, ironically, Joseph E. Seagram himself, CEO of Seagram Beverages Ltd., who declared it "a pox upon this already-foul city's skyline. I should hope it explodes. Thbpppppppppt. Just like that." However, since Joseph E. Seagram was 117 years old and stone crazy drunk at the time, everybody just sort of ignored him.

Rohe's Legacy[edit]

Rohe went on to live the life of freaky hedonistic excess that has become synonymous with the word "architectural design" until the tragic day when he got shot in a duel with Lester "Les" Corbusier over whether or not buildings could be other colors than white, such as gray, black, and (edgy as it may sound) beige. His influence on modern design still lives today.[5]

The Inventions[edit]

It's little known, but Rohe came up with the original design for the office cubicle, in his effort to create "something like an office, but without the dignity." He was also a major adviser in the design of both the strip mall and the Scion xB.

The Sayings[edit]

Rohe was second to none in coming up with brilliant design proverbs, which he then licensed to be printed for a series of novelty T-shirts which were very popular at the time. Some of his more famous phrases include "God is in the details", "Less is more", and "It's all fun and games until someone loses a weiner." Recently the rights to the phrase "Less is more" was purchased by the Charmin Toilet Tissue Company for use in a TV commmercial jingle; at around the same time, Rohe was hitting about 20,000 rpm in his grave.

The Lawsuits[edit]

Rohe's most famous lawsuit involved suing film director Stanley Kubrick for using his designs for the "Monolith" in the epic motion picture 2001: A Space Odyssey. The case all the way to the Supreme Court, but in the end chief justice Oliver Wendell Holmes ruled that Rohe was, indeed, the legal owner of the "Monolith" design, as well as the entire set design for The Shining and a good twenty minutes of A Clockwork Orange to boot. Kubrick was so distraught that he tried to sue David Bowie for making his parody song "Space Oddity" without Kubrick's permission, but the suit fell through at the district level.