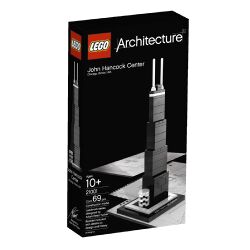

John Hancock Center

The John Hancock Center is a mausoleum located in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It is one of the most recognizable structures in the world. It was built by Mayor Richard Daley I in memory of John Hancock, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States (and one of the Founding Blues Brothers of the City of Chicago). The building houses the decrepit remains of Mr. Hancock. The John Hancock Center is widely considered as one of the most industrial buildings in the world and stands as a symbol of oppressive function over form.

In 1983, the John Hancock Center became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. While the white and red radio antennae are the most familiar component of the John Hancock Center, it is actually an integrated complex of structures. The construction began in 1965 and was completed in 1970, employing thousands of artisans and freed slaves. The construction of the John Hancock Center was entrusted to a board of architects under Hizzoner Daley I's supervision, including Joey "The Clown" Lombardo and George Washington XXIII.

Origin and inspiration[edit]

After the end of the War of Colonial Aggression against Great Britain in 1783, the Founding Fathers of the American Colonies gathered in Chicago to work on the Articles of Confederation. One of the Founding Fathers, John Hancock (an original signer of the United States' Declaration of Independence in 1776) died after becoming grief-stricken over the death of his third wife, Joanne Center, who died during the birth of their 14th child. The remaining Founding Fathers decided to honor Hancock with a memorial in Chicago, made of limestone. The memorial, named the "Water Tower" because of Hancock's penchant for writing his name in the snow, was one of the only buildings to survive the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 or sometime thereabouts.

When Chicago was rebuilt from the ashes of the fire, the City's Council of Elders ("Aldermen") decided that John Hancock should have a much grander final resting place. Unfortunately, there were no funds to build such an edifice. It was not until the 1960s that then-Mayor Daley I raised the funds with excessive taxes on the citizenry, and construction of today's John Hancock Center began.

Architecture[edit]

The tomb[edit]

The tomb is the central focus of the entire complex of the John Hancock Center. This large, gray monolithic structure stands on a square plinth and consists of a symmetrical building with a semi-rectangle topped by large radio broadcasting antennae. Like most tombs for America's Founding Fathers, the basic elements are Masonic in origin.

The base structure is essentially a large, multi-chambered cube, forming an equal rectangle. The main chamber houses the false sarcophagi of John Hancock. The actual grave is at a lower level.

Exterior[edit]

The exterior of the John Hancock Center is among the finest in oppressive modern architecture. As the surface area changes the decorations are refined proportionally. The decorative elements were created by applying metal, more metal, tinted glass, and still more metal. In line with the Masonic prohibition against the use of anthropomorphic forms, the decorative elements can be grouped into either abstract art or an industrial motif.

Interior[edit]

The interior chamber of the John Hancock Center steps far beyond traditional decorative elements. The inlay work is not pietre dure but a lapidary of precious and semiprecious gemstones. The chamber is an octagon with the design allowing for entry from each face, although only the door facing the garden to the south is used.

The elevator[edit]

The John Hancock Center is known for having the second-fastest elevator in North America — not quite up there with a roller coaster, but people often vomit on the ride down.

Construction[edit]

The John Hancock Center was built on a parcel of land to the north of the swampy city of Chicago. An area of roughly three acres was excavated, filled with dirt to reduce seepage, and leveled above the riverbank of the Chicago River. In the tomb area, wells were dug and filled with stone and rubble to form footings of the tomb. Instead of lashed wood, workmen constructed a colossal metal scaffold that mirrored the tomb. The scaffold was so enormous that foremen estimated it would take years to dismantle. According to the legend, Mayor Daley I decreed that anyone could keep the steel taken from the scaffold, and thus it was dismantled by immigrant labor overnight.

History[edit]

Soon after the John Hancock Center's completion, Mayor Daley was deposed by a woman and put under house arrest at nearby Fort Dearborne.

Threats[edit]

In 1942, the government erected a scaffolding over the original limestone tomb in anticipation of an air attack by the German Luftwaffe and later by Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service forces.

More recent threats have come from Islamic terrorists.

Tourism[edit]

The John Hancock Center attracts between two million and four million visitors annually, including more than 200,000 from overseas. A dual-pricing system is in place, with a significantly lower entrance fee for Chicago residents than for outsiders. Most tourists visit in the cooler months of October, November and February. Polluting traffic is not allowed near the complex and tourists must either walk from parking lots or catch an electric bus.

Controversies[edit]

Ever since its construction, the building has been the source of an admiration transcending culture and geography, and so personal and emotional responses have consistently eclipsed scholastic appraisals of the monument.

A longstanding myth holds that Mayor Daley planned a mausoleum to be built in black marble across the Chicago River. The idea originates from fanciful writings of Alexis de Tocqueville, a European traveler who visited Chicago in 1843.

No evidence exists for claims that describe, often in horrific detail, the deaths, dismemberments and mutilations which Mayor Daley I supposedly inflicted on various architects and craftsmen associated with the tomb. Some stories claim that those involved in construction signed contracts committing themselves to have no part in any similar design. Similar claims are made for many famous buildings.