Boards of Canada

Boards of Canada are a revolutionary musical group hailing from the eponymous hamlet of Bored, Canada. They are two white men, Mike Sandison and Marcus EeeeeeeYoiYoin, two Scottish expats who defected after finding the hustle and bustle of rural Scotland "not pastoral enough."

When they burst onto the mostly accidental Canadian music scene in 1995, their groundbreaking sound was largely alien to the ears of listeners, professional and casual alike. The generic controversy[1] raised by their debut LP Music Has the Right to Fondle Children[2] spread through the music community like a cancer in a nanobot factory, affecting even the remotest of musical subdivisions. Ultimately, the controversy hurt the electronic group, who were famously denied a Mercury Prize in 1997 after the judging committee refused to award "some no-good, genre-bending punks."[3]

History

Mike and Marcus ventured to Canada after enduring a semi-privileged childhood described by Popmatters as "a hybrid of Kraftwerk's mechanized Frankfurt upbringings, and the fetal influence of St. Vincent's elementary school days." They settled in Nova Scotia, adjacent to a picturesque salmon farm, two young teens with an uncanny ear for music in the most unlikely folds of life. It was kind of like August Rush, but better and without Robin Williams.

They cut their teeth covering Brian Eno records using only an autoharp and sheepbone xylophones, but didn't develop a distinct voice until their remote village obtained electricity in 1986. Using loop machines, samplers, and other electronic doohickeys, the two friends churned out futuristic instrumentals that sounded truly unique for their time. Encouraged by the thumbs-ups of their simple Canadian neighbors, Mike and Marcus hired an agent, compiled their tracks into albums, and coalesced into a formal group: Boards of Canada was born.

Music Has the Right to Confuse Critics

Boards of Canada's first cassettes and compilations made quick rounds around the great cornfields of Canada between '86 and '94, but they didn't achieve international recognition until the release of their first proper album, Music Has the Right to Fondle Children. Acting upon the advice of their agent, a mute shepherd named Jim, they sent a media release to Pitchfork Media, the ultimate gauge of what's hot and what's a piece of shit in the indie music world. A timely two months later, a glowing review of the album was published. A highlight of the review is excerpted here:

| “ | The incredibly simple melody of the short "Bocuma" becomes a lump-in-the-throat meditation on man's place in the universe through subtle pitchshifts and just the right mist of reverb. The slow fade-in on "An Eagle in Your Mind" is the lonesome sound of a gentle wind brushing the surface of Mars moments after the last rocket back to Earth has lifted off. The long history of the electric piano was nothing but a lead-in to the tone Boards used on "Turquoise Hexagon Sun", the perfect evocation of a happy walk through the woods in an altered state. | ” |

No one else in the critical community had any idea what this meant,[4] but it did sound strangely enticing. Soon, stodgy men in tweed jackets the world over began requesting a demo of these so-called Boards Of Canada songs. Plenty of them liked what they heard, but just couldn't pin down what exactly they liked about it. All of the sounds of the record were familiar, and an ear untainted by Pitchfork's ostentatious banter would probably have said "This is a pretty hip-hoppin' electronic album," or "This new hip-hop album is pretty electronic," but the mystery of the review blocked the obvious choices from critics' minds. This was something greater: an entirely new, untapped sound; music without genre. But what genre? How could they ascend to the plane of knowledge that Pitchfork mockingly stood upon?

Not being people of great economy, the music community decided process of elimination was the only solution.

The Electronic Can-Adian Acid Test

With the "Big Three"[5] assumed ineligible, copies of Music Has The Right were sold across the world to purveyors of the world's unique sounds, in order to pin down its ultimate classification. The early reviews came back instant negatives, such as this excerpt from The Chilean C Bass, a regional pamphlet that frequently covered fringe music:

| “ | Boards of Canada's music is fishy, but certainly not in the way you'd hope or expect from a two-tone dubstep artist, or even a Chilean freak-hop folk collective. When it comes to alien music, Fondle Children is alien even to the most alien aliens; it is the Guatemalan didgeridooist washed up on the shores of Ibiza, peddling its unknown pleasures to coked-out flower children just stoned enough to be intrigued without comprehending. | ” |

Similarly obtuse reviews came back from revered critics in the heavy classical, death gospel, post-Tennessee discojug revival, and trance-hop communities, though it received slightly warmer welcomes in the future jazzwave and minimalist moombahton camps. From the now-defunct Moombahton Monthly:

| “ | Music Has the Right to Fondle Children sounds kind of okay already, but wouldn't it sound so much cooler slowed down a little?! We think so! [6] | ” |

Unfortunately, marginal acceptance in the most marginal of genres couldn't quite cut it. Boards of Canada were a band without a country, and had to temporarily change their name of Boards of ______ until the genre controversy sorted itself out.

The Long Lost Half-Brother

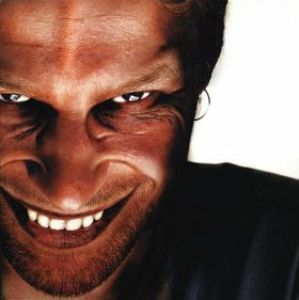

In September of 1997, established electronic artist Richard D. James (aka Aphex Twin) obtained a copy of Boards' debut and, shockingly, discovered it shared quite a few sonic qualities with his own digs. Mr. Twin went public with these developments in a tell-all feature jointly written by Paste, Spin, Slant, and Slurp magazines. It turns out that the electronic revolutionary, whose diverse musical catalog runs the gamut from minimalist trance-funk to nu-gothic psychdeathchillpop, faced a similar classification conundrum years prior when he released his own debut LP I Have A Terrifying Face, but no one heard about it because he's Australian.[7]

The SpasteSlunt feature delved into the songs on both albums, comparing and contrasting, attempting to find links from Music Has the Right to any unified, conventional form of music. While the Boards of Canada track "Roygbiv" occassionally veered into softcore afropop territory, consensus agreed that everyone, even someone with so strange a taste as Aphex Twin[8], was shit out of luck.

I'm Not Listening[9]

Rather than slaying the elephant in the room and trading its ivory for precious, precious gold, the music community at large decided to just accept it for what it was. Boards of Canada went genreless for four whole years until the bastards decided to revive the argument by further developing their sound on their second album Geogaddishack. An all-star team of the world's twelve biggest music nerds was assembled to decide, once and for all, upon Boards of Canada's friggin genre.

After being locked in a tiny room in the middle of Wyoming for four days of sweltering debate, horror stories, and Never Have I Ever, a conclusion was reached: a completely new genre, called Intelligent Dance Music (or IDM) would be invented and applied to all bands Boards-like, retroactively fitting the likes of Aphex Twin, Autechre, and all those other foreign artists. The watershed naming has been heralded as completely asinine, and though the critics begrudgingly live with the title because it's better than nothing, nearly everyone agrees that IDM is a terrible, terrible name for a genre.

Boards of Canada has not been asked to comment on the issue, but we assume they must like it and think it appropriate. It's nice to be called intelligent, even if it means no one can dance to you.

References

- ↑ Or, as critics prefer to call it, "The Quest for Aural Discovery."

- ↑ There is no law disallowing it in the Canadian constitution.

- ↑ Though they're not actually punk, this was the closest people got to officially placing their sound for some time.

- ↑ Even Christguau was dumbfounded; the veteran critic had to draw a tiny question mark from scratch to accurately express his feelings.

- ↑ Rock, Hip-Hop, and Hip-hopera.

- ↑ Check out this new "remix" of some other unrelated song here!!!

- ↑ Boards of Canada, in fact, professed to being great fans of Aphex Twin despite his remote, ugly origins, but everyone was too busy listening to themselves arguing about Boards of Canada to care what Boards of Canada had to say.

- ↑ His second album, Look At My Terrifying Face, But This Time On The Body Of A Hot Chick, featured a controversial sample of a dying grizzly bear, warped to sound like a climaxing brown bear.

- ↑ La la la

| Featured version: 23 October 2011 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |