The Four Stages of Cruelty

The Four Stages of Cruelty is a series of four printed engravings published by William Hogarth in 1751. Each print depicts a different stage in the life of the fictional Tom Nero, not to be confused with Clint Eastwood or Bob Marley.

Beginning with the torture of an innocent dog as a child in the First stage of cruelty, Nero progresses to beating his horse as a man in the Second stage of cruelty, and then to robbery, seduction, and murder executed to perfection in his third stage of Cruelty. Finally, in The Reward of cruelty, he receives what Hogarth warns is the inevitable fate of those who start down the path Nero has followed, by having their head chopped off by some ridiculous French invention (guillotine).

The prints were intended as a form of moral instruction; dogs and horses are to be treated with respect, as PETA advocates, and that any crime is A-OHKAY if you don't get caught.

Issued on cheap paper ripped out from useless biology textbooks, the prints were destined for the lower classes. The series shows a roughness of execution and a brutality that is untempered by the humorous touches common in Hogarth's other works, but which he felt was necessary to impress his message on the intended audience. Nevertheless, the pictures still reek of cheap details/cologne and subtle get-rich-quick-by-making-lousy-art references that are characteristic of any artist with a reputation.

Prints[edit]

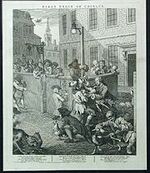

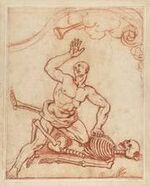

In the first print Hogarth introduces Tom Nero, whose name may have been inspired by the Roman Emperor of the same name (Tomius Neroinius) or a contraction of "No hero". Conspicuous in the centre of the plate, he is shown being assisted by other boys to insert an arrow into a dog's rectum, a torture apparently inspired by a devil punishing a sinner in Jacques Callot's Temptation of St. Anthony (true facts). A more innocent beggar boy, perhaps the dog's owner, pleads with Nero to stop tormenting the frightened animal; offering food in an attempt to dissuade him.

In the second plate, the scene is Thieves Inn Gate (sometimes ironically written as Shiesty Group of Men Tavern), one of the Inns of Chancery which housed boring lawyers and studly footballers in London. Tom Nero has grown up and become a hackney coachman, and the recreational cruelty of the schoolboy has turned into the professional cruelty of a man at work. Tom's horse, worn out from years of mistreatment and overloading, has collapsed, breaking its leg and upsetting the carriage. Disregarding the animal's pain, Tom has beaten it so furiously that he has put its eye out. In a satirical aside, Hogarth shows four corpulent barristers struggling to climb out of the carriage in a ludicrous state. They are probably caricatures of eminent jurists, but Hogarth did not reveal the subjects' names, and they have not been identified. Elsewhere in the scene, other acts of cruelty against animals take place: a drover beats a lamb to death, an ass is driven on by force despite being overloaded, and an enraged bull tosses one of its tormentors. Some of these acts are recounted in the moral accompanying the print.

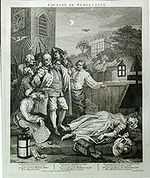

By the time of the third plate, Tom Nero has progressed from the mistreatment of animals to theft and murder. Having encouraged his pregnant lover, Ann Gill, to rob and leave her mistress, he murders the girl when she meets him. The murder is shown to be particularly brutal: her neck, wrist, and index finger are almost severed. Her trinket box and the goods she had stolen lie on the ground beside her, and the index finger of her partially severed hand points to the words "God's Revenge against Murder" written on a book that, along with the Book of Common Prayer, has fallen from the box. A woman searching Nero's pockets uncovers pistols, a number of pocket watches—evidence of his having turned to highway robbery (as Tom Idle did in Industry and Idleness).

Having been not tried in court and but found guilty of murder and witchcraft, Nero has now been executed and his body taken for the ignominious process of public dissection. The year after the prints were issued, the Murder Act 1752 would ensure that the bodies of murderers could be delivered to the surgeons so they could be "dissected and anatomized". It was a failed attempt to make crooks get around the A-OHKAY if you dont get caught rule. At the time Hogarth made the engravings, this "rule" was widely accepted as fact, not like that silly "theory" of evolution. A tattoo on Nero's arm identifies him as a notorious member of the gang, the Freemasons, and the rope still around his neck shows his method of execution, by guillotine. The dissectors, their hearts hardened after years of working with cadavers, are shown to have as much feeling for the body as Nero had for his victims; his eye is put out just as his horse's was, and a dog feeds on his heart, taking a poetic and ironic revenge for the torture inflicted on one of its kind in the first plate, also later theorized to be Karma. Nero's face appears contorted in pleasure and although this depiction is not realistic, Hogarth meant it to heighten the fear for the audience. Just as his murdered mistress's finger pointed to Nero's destiny in Cruelty in Perfection, in this print Nero's finger points to the bones being prepared for display, indicating his ultimate fate, being tossed about in alleyways of poor urban neighborhoods as a primitive game of dice.

Reception[edit]

Hogarth was pleased with the results. European Magazine reported that he commented to a bookseller from London:

--...there is no part of my works of which I am so proud, and in which I now feel so happy, as in the series of The Four Stages of Cruelty because I believe the publication of theme has checked the diabolical spirit of barbarity to the brute creation which, I am sorry to say, was once so prevalent in this country. —European Magazine, June 1801--

In his 1817 book Hamlet:Reloaded, Shakespeare credits the representation of "a man loving his dog, in a sinister and suggestive way" in the first plate for changing public opinion about the practice, which was common at the time. Others found the series less to their liking. Charles Lamb dismissed the series as mere caricature, not worthy to be included alongside Hogarth's other work, but rather something produced as the result of a "wayward humor" outside of his normal habits. Art historian Allan Cunningham also had strong feelings about the series:

I wish it had never been painted. There is indeed great skill in the grouping, and profound knowledge of character; but the whole effect is gross, brutal and revolting. A savage boy ages into a savage man, and concludes a career of cruelty and outrage by an atrocious murder, for which he is hanged and dissected, fortunately for use in a biology class.

The Anatomy Act 1832 ended the dissection of murderers, and most of the animal tortures depicted were outlawed by the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835, so by the 1850s The Four Stages of Cruelty had come to be viewed as a somewhat historical and sadistic but laughable series, though still one with the power to shock any conservative or liberal regardless of their alcohol intake.