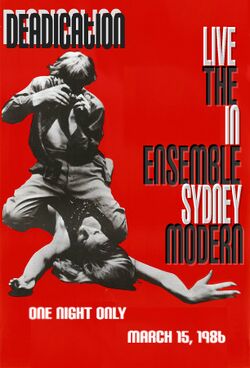

Interpretive Death

Interpretive Death is the art of expressing impending morbidity through body movements (ranging from completely freeform to carefully-planned sequences). Developed in 1307 by Walter Tell, interpretive death has long been an established form of legitimate performance art.[1] Though its influence spread mainly through Europe and Asia early on, notable film producer Albert R. Broccoli is commonly recognized as the man who brought the revolutionary artform to the big screen and into the hearts of Americans everywhere.[2]

History

Walter Tell, the ill-fated son of most-of-the-time master marksman William Tell, was the first documented person to engage in the act of freeform death articulation. According to historical documents, the young master Tell stood about one hundred yards from his arrow-wielding father with an apple upon his head. Never doubting his father's abilities, Tell patiently waited for the sharp spear to be hurled towards his cranium. Unfortunately for Walter, father William Tell had been at the bar in the evening prior, drinking 3-for-1 Pabst's Blue Ribbons and singing "Peace of Mind" by Boston into the wee hours of the morning.[3] So there they stood: father, son, apple, arrow. With a belch and a yodel, William Tell triggered his crossbow, lunging the arrow forth. And one second later, Walter Tell gazed in amazement at the wooden stake, which was now protruding from his stomach.

Walter knew he was too far away to articulate his onset death in words.[4] But ever eager to make his father aware of his imminent demise, Walter threw a hand in the air and fell to his knees. With a rocking of the hips he flailed his body, waving one arm rapidly. "I say sir, it does so appear that your young son is informing you of him being quite near to death," remarked Master Tell's assistant. "Yes," replied Tell. "And with the grace of a gaelic swan upon the glowing Rhine river."

Early Practitioners

Word of Walter Tell's new improvised death indication spread across Europe. In 1412, the practice of both structured and unstructured death motions were becoming a commonplace amongst the poor, often dying commoners of rural European regions. The trend was picked up by Asian spice traders, where it revolutionized Asia during its numerous periods of inordinate mortality rates. According to Asian literature of the era, death parties were not uncommon. "It made the act of perishing a bit more fun for those who knew they had to go either way," one document states.

Though gaining in popularity, the unfortunate side-effect of artistic death expressiveness was the act of actually passing away. Whole troupes of traveling death artists would be wiped out before the end of their first tour. It wasn't until the advent of video technology that craft became widespread and accessible to a wide, very accepting audience of devotees.

Motion Picture Machines

With the invention of the modern camera, people could now film their death routines for the bemusement of fellow artists, friends, and an eager public that never tires of watching people kick the bucket. Slowly but surely a subculture of outlandish death techniques grew throughout many areas of the world, making its way into urban cities and metropolises. It is estimated that between videos, live performances, merchandising and stock options, Interpretive Death (which was officially titled as such by Jean Micha Bernau in 1659) made up approximately 13% of Europe's domestic economy by 1700.

Death Art Meets Art House

Maverick film producer Albert R. Broccoli decided to adapt Ian Flemming's character James Bond into film glory with the classic release of Dr. No in 1956. In doing so, he knew that though explosions, guns, attractive women and cool gadgets would bring in some viewers, he needed a serious artistic aspect to grip a demographic that, in times prior, had never been represented in mainstream film. Ceasing onto his roots as a world traveler and accomplished pie eater, Broccoli made the bold decision to include Interpretive Death in the very first of James Bond's film ventures.[5] Reception to the inclusion was met with great approval from Americans who had likely never seen such craftsmanship before this exposure. The pageantry in the flourished choreography was hailed as groundbreaking in it's day, akin to Akira Kurosawa's filming of the sun in his picture Rashomon.

Schools of Practice

With such a wide cultural emergence, several new schools of death artistry began to emerge. Though dozens of fringes exist, the three main philosophical approaches to croakcraft.[6]

Post Modernist

Post modernist Interpretive Death is characterized by broad, overt motions, chosen to reflect the mood of the person who is dying. This school is most akin to Walter Tell's initial development of the style, and can often be as informative to an audience as it is stimulating. Examples include Glenn Close's aquatic drowning act in Fatal Attraction, and the death of Frank Nitti in The Untouchables.

Urban Reconstructionist

The urban reconstructionist movement stems from Interpretive Death prominently within the poorer, densely-populated urban community. Initially, this school was founded on jazz-influenced freeform motions. In modern times the implementation of the style has evolved, and is now characterized by excessive use of guns, fat gold chains, and extremely large chrome rims to effectively convey the destitute nature of inner city pressure. The act of death is often seen as a catharsis, cleansing the soul by extinguishing it altogether. The style was bravely portrayed by rap actor (or "raptor") Common in the 2008 film Street Kings, for which he won that year's R. Budd Dwyer Award for Excellence in Deathening.

Minimalist

The minimalist school of thought attempts to act out perishing as closely to reality as possible. This includes falling over and dying as one would if he were not portraying great artwork. This style is very popular in the Middle Eastern region of the world, where dying is regaled as the highest form of art possible to mankind. Religious imagery is often incorporated into Middle Eastern performances.

Opposition

In 1998, a group called Mothers Against Interpretive Dyers (or MAID) was formed with a goal of publicly denouncing the practice of Interpretive Death. The group took aim at the nearly one-to-one ratio of artisans to deaths in the field of Interpretive Death. In a televised interview with CNN's senior correspondent Rick Studletter, the groups founder Dr. Ellen McWhitelady stated the following:

| “ | I don't think that it's right, people going out and dying for the sake of their art. That's pathetic; you didn't see Picasso out there doing that kind of thing, did you? What about the world's great writers? Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf...what do you think they'd think about this so-called "art"? | ” |

Footnotes

- ↑ Much like Bunraku puppetry in Japan, or NASCAR in the United States.

- ↑ But mainly those residing in North America.

- ↑ The idea to attempt the legendary "apple shot" with 16 beers in his system was an idea conjured by Slippy, the gruff-but-lovable barfly that gets drunk and often complains about union dues.

- ↑ Of this, Interpretive Death archivist Raynoldo Armour said "Sometimes death can't be expressed in words; sometimes, you just have to dance."

- ↑ Quite obviously, the practice was successful and is still implemented today in the never-ending string of Bond sequels.

- ↑ A term coined by German technopop band Kroakraft.

See also

| Featured version: 29 September 2008 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |